L’argent, le moteur des marchés

Why inflation pessimism is premature

13 août 2025 par Simon Ward

The Kondratyev cycle describes a tendency for global inflation – or the price level in earlier centuries – to reach major peaks / troughs every 54 years on average.

The highest peaks in global inflation in the first and second halves of the last century occurred in 1919 and 1974 respectively, suggesting another peak in the late 2020s.

US-centric analysts often wrongly place the last peak in 1980, as US annual consumer price inflation reached a higher high in that year. This was not true of a GDP-weighted average of CPI inflation rates across major economies, nor of US producer price inflation, which also reached a maximum in 1974.

Cycle troughs typically occur about two-thirds of the way through the interval between peaks, i.e. about 36 years after one peak and 18 years before the next. The annual change in global / US consumer prices reached a low in negative territory in 2009, consistent with this pattern and further supporting the expectation of a late 2020s peak.

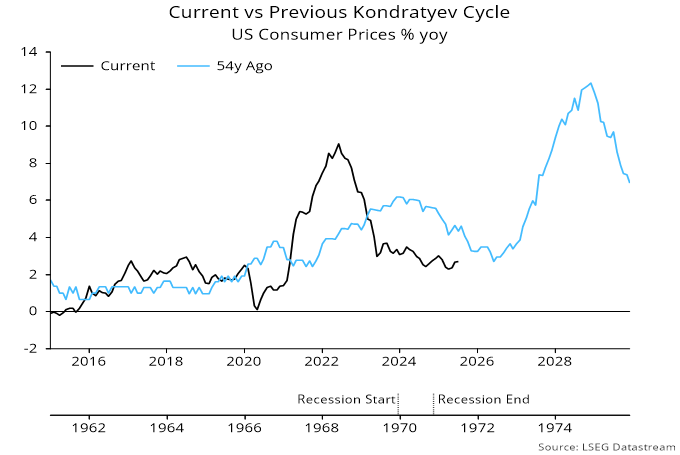

Numerous commentators have drawn a parallel between recent / current US inflation experience and the early 1970s. Annual CPI inflation reached a post-Korean war high in 1969, fell back into 1972, then embarked on a bigger climb into the 1974 peak. The suggestion is that the rise into 2022 is the analogue of the late 1960s increase and another, bigger upsurge will unfold in 2026-27 – see chart 1.

Chart 1

Proponents of this view cite tariffs, large budget deficits and erosion of Fed independence as factors conducive to another inflation pick-up.

Current monetary trends, however, differ from the early 1970s, suggesting that such concerns are premature.

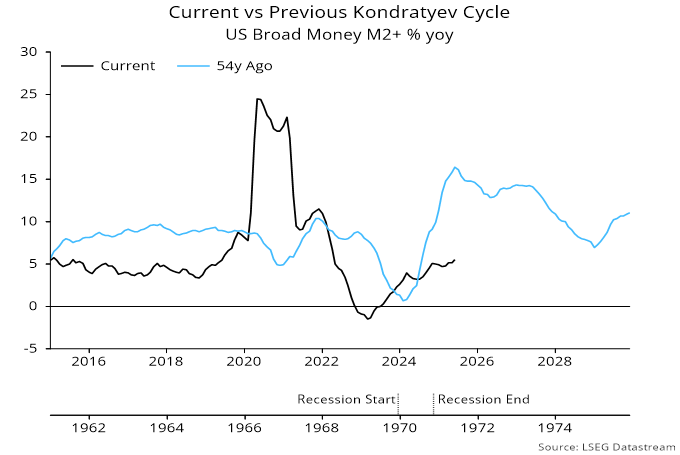

The 1967-69 inflation pick-up was preceded by a rise in annual broad money growth to above 10%. Fed rate hikes caused money growth to slump, pushing the economy into a recession in 1970. The Fed responded by fully reversing the increase in rates. Money growth surged into the mid-teens in 1971, laying the foundation for the 1972-74 inflation upswing – chart 2.

Chart 2

Fed tightening in 2022-23 also caused money growth to slump but the economy avoided a recession, resulting in a much more muted policy reversal. Money growth has recovered but only to a “normal” level by historical standards.

The monetary conditions for a second inflation rise into the Kondratyev peak, therefore, have yet to fall into place.

How could this change? One possibility is that lagged effects of policy tightening and tariff damage result in a recession and / or significant labour market weakness, triggering panic Fed easing that pushes money growth up further – a delayed 1970 scenario.

Alternatively, the Trump administration could wrest control of the Fed and push rates lower regardless of economic conditions.

A third possibility is that the Treasury increases monetary financing of the deficit, for example by relying on issuance of bills – mostly bought by banks and money funds – rather than notes and bonds.

The Kondratyev cycle is global so another scenario is that the monetary impulse for higher inflation comes from outside the US, for example through a combination of reflation in China and a further surge in already strong Indian money growth.

Large inflation swings, in either direction, often occur when policy-makers, and economic agents generally, are facing the “wrong” way (as was the case in 2020). The final ascent into the Kondratyev peak may require a recession / deflation scare first.