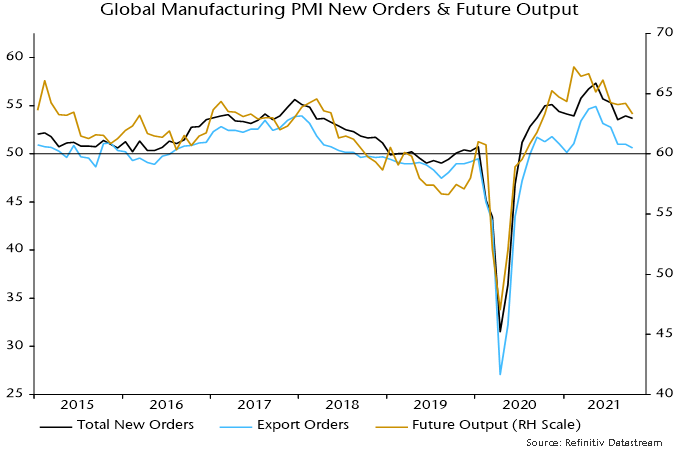

Cautionary signs from abroad.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) began tightening policy in March 2022, ahead of most major central banks and has recently been among the first to pause. However, there have been some surprising developments in other countries over the last month, and it is worth examining whether they have any implications for Canada.

For instance, the Bank of England began raising rates even before the BoC. Like Canada, the UK is sensitive to interest rate increases, particularly as mortgage interest rates are typically fixed for two to five years. Despite Brexit reducing mobility overall, the UK saw a net migration inflow over the past year, leading to a 0.65% population gain. Although slightly higher than pre-pandemic levels, this growth is far from the 2.7% population increase seen in Canada. Furthermore, the UK economy has slowed but is facing the highest inflation rate in Europe and one of the highest inflation rates among developed markets, with the CPI annual rate stalling at over 10% year over year (y/y) in eight of the last nine months (see Chart 1). Core inflation is at 6.2%, not far from its 30-year highs of last summer. The implication that inflation is difficult to wrestle is potentially concerning, yet UK inflation has remained high in no small part due to extended supply pressures emanating from Brexit and more rigid trade rules.

Chart 1: UK inflation highest among developed peers

Source: Statistics Canada, Australian Bureau of Statistics, UK Office for National Statistics, Statistics New Zealand, Macrobond

In early April, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) surprised the market by increasing the Official Cash Rate by 50 basis points (bps) to 5.25% due to concerns over higher near-term inflation readings. Supportive fiscal policy combined with rebuilding after recent storms may add fuel to upside pressures. The RBNZ has matched the Federal Reserve (Fed) for the largest cumulative rate hikes and may still increase rates further.

In Australia, the central bank paused in April, but quarterly inflation reports for both headline and its core metric of trimmed CPI, while modestly lower than expected, still exceeded the central bank’s targets at 7% y/y and 6.3% y/y, respectively. In early May, the Reserve Bank of Australia surprised the markets with a 25-bps rate hike, taking the target cash rate to 3.85%, citing high services prices as a concern. It noted that inflation may take “a couple of years” to return to the top of its target range.

Are higher rates a material risk?

Canada is, like many other countries, currently adjusting to past rate hikes. On the surface, the country has appeared resilient in the face of short-term adjustable rate mortgages, high sensitivity to interest rate increases because of large debt, and its broad exposure to the cyclically-sensitive commodities sector. In spite of these factors, there have been no banking stresses, fewer mass layoffs and no sharp rise in mortgage delinquencies. But as with countries elsewhere, at least for the near term, we should not underestimate the potential for a surprise on the side of further policy tightening. Indeed, the April BoC Summary of Deliberations showed that the discussion leaned towards whether rates needed to rise again. There are reasonable arguments for this.

While it may be too early to call it a trend, the Canadian spring housing market appears to be picking up steam. New listings to start the spring season were the lowest for any March over the past 20 years, and demand from natural household formation and new immigrants has been strong. This has coincided with a peak in mortgage rates as the BoC stopped hiking rates. Five-year mortgage rates have fallen from last October’s peak of 5.88%, with the latest 75 bps of BoC rate hikes having little effect. As a result, house prices in major cities have risen for the last two months.

Fiscal policy is adding stimulus, with provincial governments adding about $6 billion in new support measures and tax reductions and the federal government more than doubling that to $13 billion. These support measures are delaying a material slowdown and working against tighter monetary policy. Perhaps the most important lesson we take from other countries is that overall inflation is still at risk of remaining above target, particularly with Canadian economy-wide average hourly wages running at over 5% (see Chart 2).

Chart 2: Strong Canadian wage growth risks above target inflation

Source: Statistics Canada, Macrobond

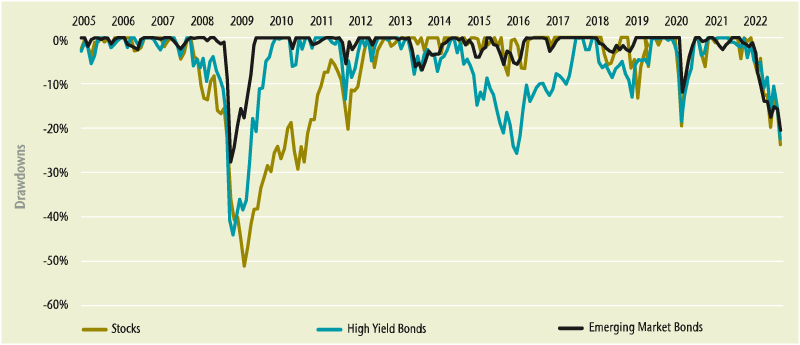

While we view the most likely scenario to be no further rate hikes, the longer inflation is above the explicit target, the more extrapolative expectations become, making it harder to bring inflation under control. So even if the BoC does not surprise with more rate hikes, there is a risk that monetary policy will be held tighter and rates higher for longer. This is not being priced into markets. The implications for asset prices are material; the longer rates are held high, the more stresses build and the harder it is to push problems down the road.

Capital markets

After three of the largest four US bank failures in history, it is surprising that April was one of the calmest months in markets. Volatility indices for both bond and equity markets eased, evidenced by the daily and monthly change in prices. Two areas stood out: US regional bank stocks continued to fall, led by First Republic. Secondly, the quiet world of US T-bills reflected anxieties surrounding the US debt ceiling limit. Investors kept purchases below one month to avoid debt ceiling default risk, pushing yields down and the spread to 3-month T-bills to historic wide levels.

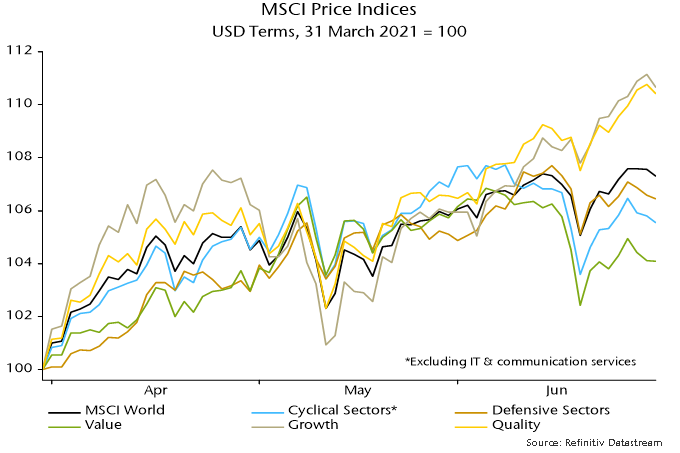

Bond yield changes were subdued in Canada over the month, while corporate credit spreads tightened, leading the FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index to rise 0.98%. A decent corporate earnings season contributed to the sanguine market sentiment and equity markets recovered from the March upheaval. The MSCI ACWI Index gained 1.4%, led by developed markets. The S&P 500 Index rose 1.6%, although breadth was narrowly concentrated in the technology sector, which was buoyed by lower interest rates that helped boost valuations. In Canada, the S&P/TSX Composite Index outperformed, rising 2.9%. Commodities were generally weak in April, except for oil prices, where the OPEC+ group cut output at the start of the month, leading WTI to hit a peak of US$83/bbl. This was short lived and prices eased back to close the month nearly unchanged.

Portfolio strategy

Similar to other economies, Canada’s late cycle environment presents risks that are not one-sided, and central banks are unlikely to intervene aggressively in a slowdown. While recent economic releases suggest momentum is slowing, consumers are gradually using up their excess savings and businesses are exercising restraint in spending, which is a process that takes time. Meanwhile, inflation remains stubbornly high and we do not anticipate significant interest rate cuts in the near future. Our outlook indicates that a recession is the most probable scenario for the latter half of 2023.

In our fundamental equity portfolios, we continue to look for companies with strong fundamentals that can navigate slower aggregate economic growth. Our portfolio positioning emphasizes defensive strategies, with earnings stability a crucial theme at both the sector and security level. However, we are also exploring opportunities to invest in oversold cyclical companies that will likely perform during an economic recovery. Our fixed-income portfolios follow a similar theme, focusing on corporate bonds while we remain patient in our macro positioning given the possibility of tighter lending during a recession later this year. Our balanced portfolios maintain an underweight position in equities in favour of cash. We continue to assess both domestic and global data and seek out opportunities in both calm and volatile markets.