Despite ongoing macroeconomic uncertainties and some softness in business activity, financial results published from our holdings for 2023 reassured us. On average, both margins and earnings held up relatively well. Here are two examples of holdings that contributed positively during the first quarter of 2024.

Sopra Steria Group:

Sopra has historically managed mid-single digit organic growth in addition to consistent quality M&A to enhance topline growth. Its historical margins, however, have lagged larger peers like Accenture or CapGemini due to the acquisition of Steria in 2014 which was dilutive to margins [Steria was 350 basis points (bps) below Sopra’s margin], as well as some segments and geographies where management has somewhat sacrificed margins for growth. In 2023, despite additional margin dilution from recent acquisitions, Sopra achieved a 9.4% operating margin, its highest since 2011, and much closer to the 10% to 12% expectation for a major European IT service firm. This was driven by increased pricing, operational efficiencies and scale. We expect Sopra to reach and maintain this improved margin profile in the next couple of years, while maintaining a defensive end-market profile than peers. As such, we remain optimistic on the name.

Melia Hotels International:

After the initial collapse of travel in 2020, when Melia saw its sales drop 70% year over year, the resort hotel operator enjoyed explosive revenue growth due to what analysts coined “revenge travel.” While 2023 saw more normalized 14% topline growth after two years of high double-digit growth, there is still plenty of room for sustainable growth on both the top and bottom line. Despite reaching peak EBITDA from 2018, margins remain a full 200 bps before pre-COVID and there is no reason to believe pre-COVID margins cannot be reached again as the inflationary environment normalizes. Furthermore, the company announced earlier this year the sale of 38% of three of its hotels to Santander for €300 million, strengthening Melia’s balance sheet through deleveraging, while highlighting the bank’s confidence in Melia’s growth prospects. Overall, the company appears quite confident in its 2024 outlook. Despite concerns that inflation could impact discretionary spending including travel and lodging, Melia expects low double-digit RevPAR growth driven equally by price and occupancy, which seems supported by strong January and February data.

Over the next weeks, European companies will start publishing their Q1 revenues, and with it, their outlooks for 2024. The comparison basis with Q1 of 2023 could prove challenging, but we are still projecting companies to generate positive earnings growth for this calendar year. Here are some observations that tend to support our view that the economic improvement could continue:

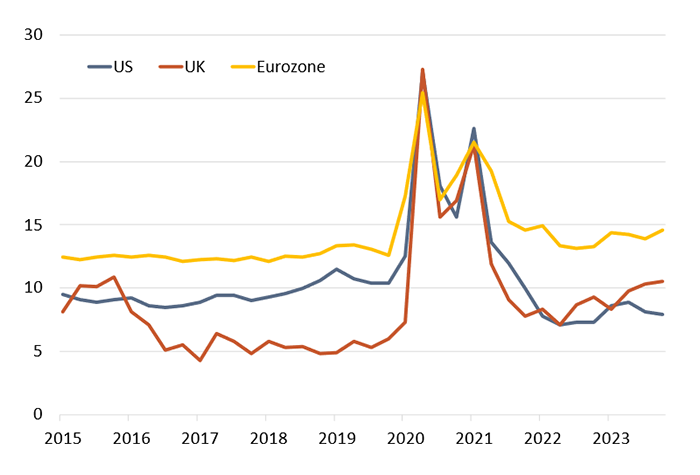

Real wage growth and savings rates are supportive: After experiencing negative mid-single digit growth in 2022, the Eurozone and the UK are now back to positive real wage growth. As a result, saving rates have started to climb and the gap with the US has widen. As shown below, EU and UK gross savings rates are very supportive compared to the US. The economic activity could react positively to a scenario where households decide to shift a portion of that disposable income into consumption.

Savings rates across the US, the UK and the Eurozone

Source: Berenberg.

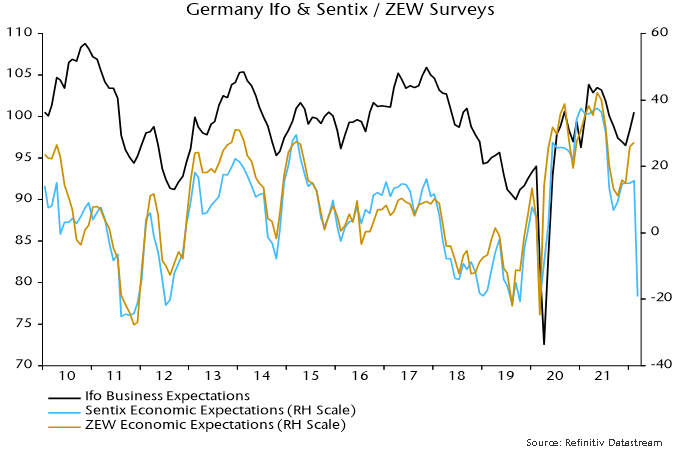

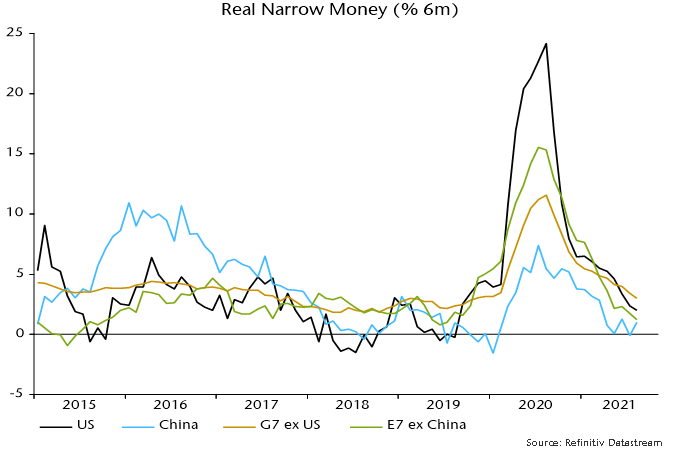

European optimism is growing: Business surveys and confidence indices are showing early signs of recovery, as indicated by the latest release on the German business outlook. Although it may not immediately translate into new orders, it could play an important role in how the second half of this year develops.

The housing market is stabilizing: Mortgage approvals in the UK bounced back in February to a level not seen since September 2022. A similar picture can be observed in Germany after two years of excessive contractions. Although corporate loans were still declining in the first quarter of 2024, we are starting to see credit conditions easing for mortgages, a first since 2021.

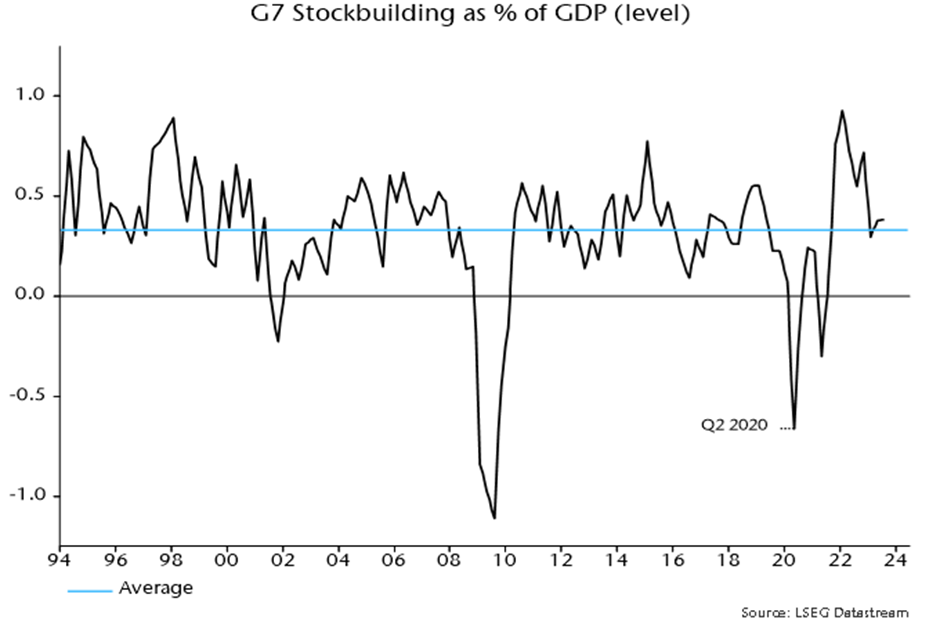

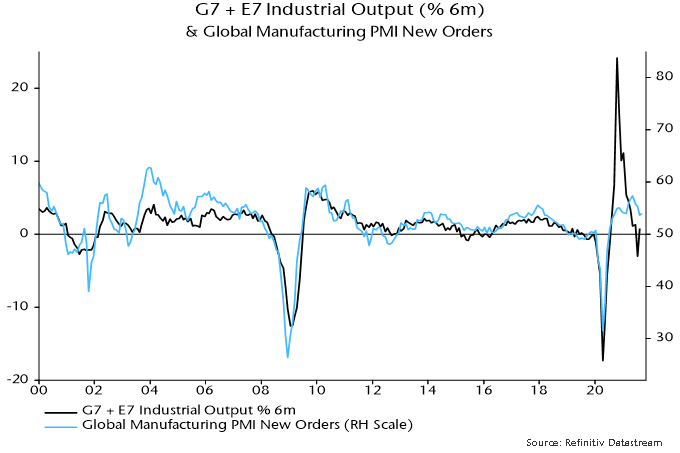

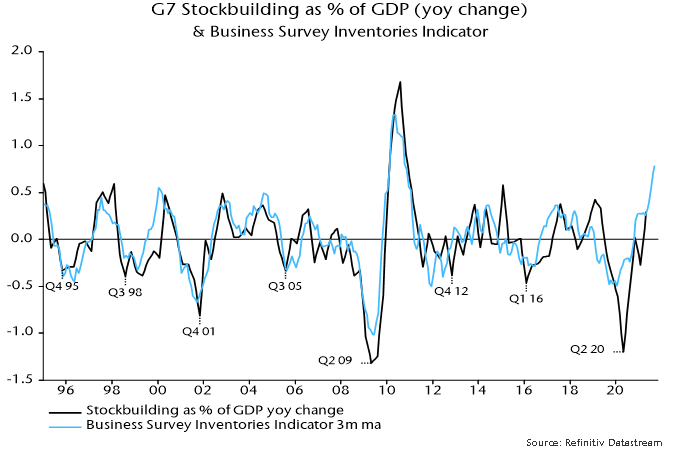

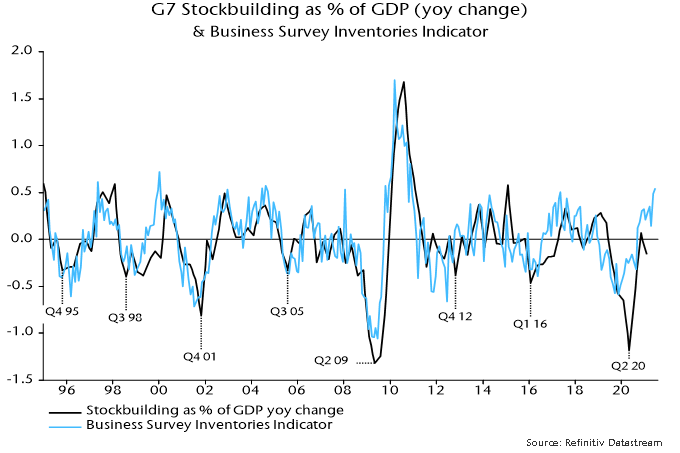

The destocking cycle is coming to an end: The destocking cycle that started in early 2023 has contributed to a very low level of stocks. Some industries might even carry too low a level of stocks in the event that pent-up demand returns in the second half. Any uplift in order intake would require a higher level of stocks, which would revitalize the manufacturing sector.

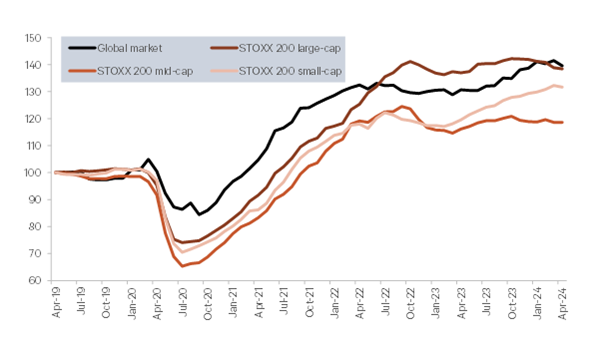

Valuation discount: The wide valuation gap that exists between Europe and Global could be narrowing as economic indicators and confidence improve. As shown by the 12-month forward earnings index below, small and mid-cap stocks are still trading at discount vis-a-vis Global. A potential rate cut, expected in June, combined with a reacceleration of demand, would likely drive small and mid-cap companies.

Forward 12-month earnings for European companies vs. the Global market

Source: Berenberg.

In a world where the unexpected has become the norm, our holdings’ resilience through last year’s ups and downs offers a sense of stability and growth potential amid uncertainty – and an opportunity to think beyond the immediate to what could be on the horizon.