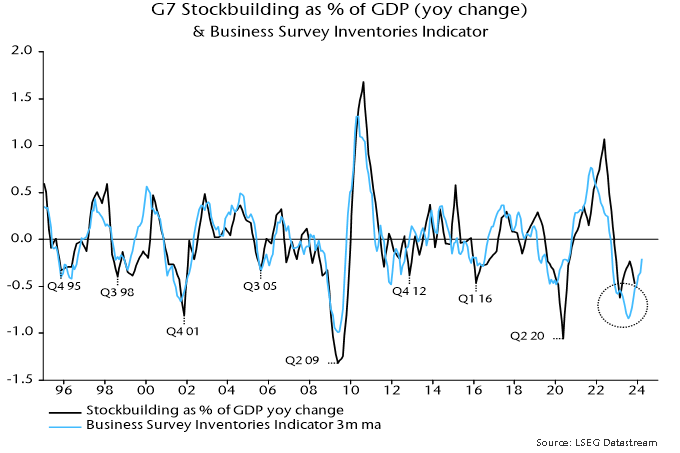

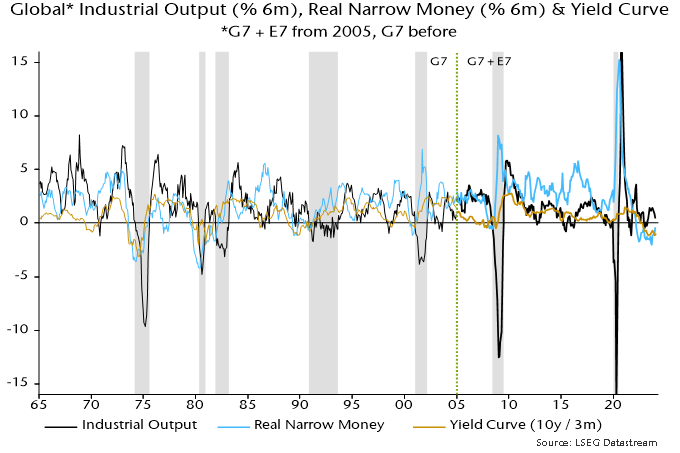

The quarterly commentary in mid-2023 noted that the cycle and monetary analyses were giving conflicting signals. The stockbuilding cycle appeared to be tracing out a low, a development usually associated with stronger performance of equities and other cyclical assets. However, greater weight was accorded to continued weakness in global real narrow money momentum, which suggested downside risk to economic activity and insufficient liquidity to support market gains.

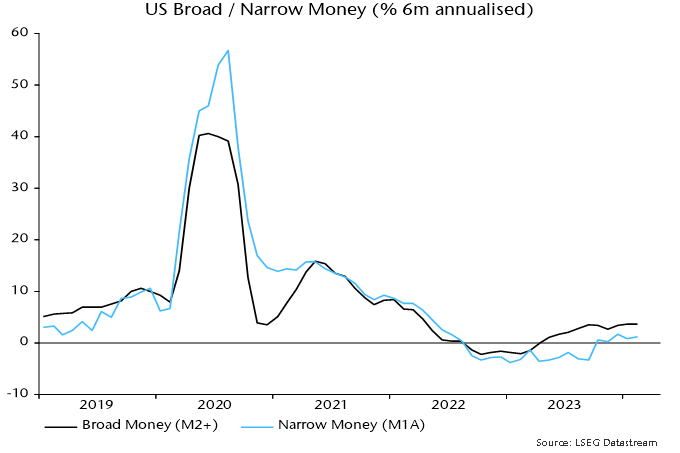

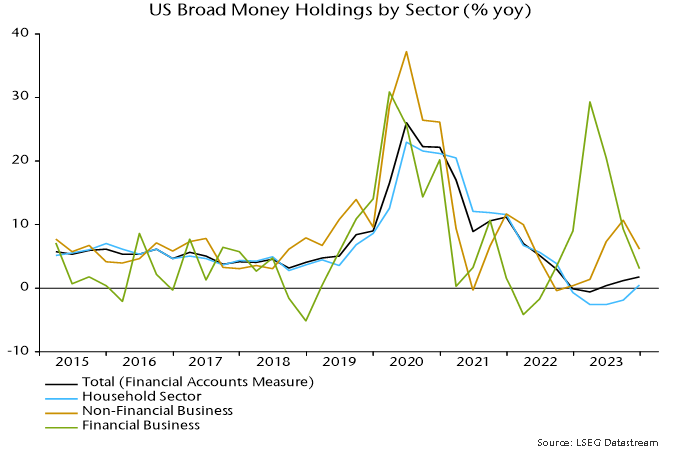

The cycle signal has so far proved the correct one, with cyclical assets rallying strongly over the past five months. Monetary conditions have been more permissive than expected, probably reflecting continued deployment of “excess” money balances left over from the 2020-21 monetary surge, as well as unusual US deficit-financing operations.

What now? Valuations of some cyclical assets appear already to discount a solid and sustained economic upswing. Global real narrow money momentum has recovered slightly but remains negative, while the level of money balances may now be below “equilibrium”. Until money growth normalises, the risk is that an initial stockbuilding cycle recovery will prove disappointingly weak or even fail, with a retest of the 2023 low. A monetary revival, meanwhile, may have been pushed back by major central banks’ caution in reversing 2022-23 policy restriction, although an easing trend is under way in EM.

Commentaries in 2022 argued that the stockbuilding cycle was likely to bottom in 2023, probably in H2, based on the cycle’s 3.33-year average length and the prior low having occurred in Q2 2020. The possibility of an earlier trough was considered, on the view that the current cycle could be shorter than average to compensate for a longer prior cycle (4.25 years).

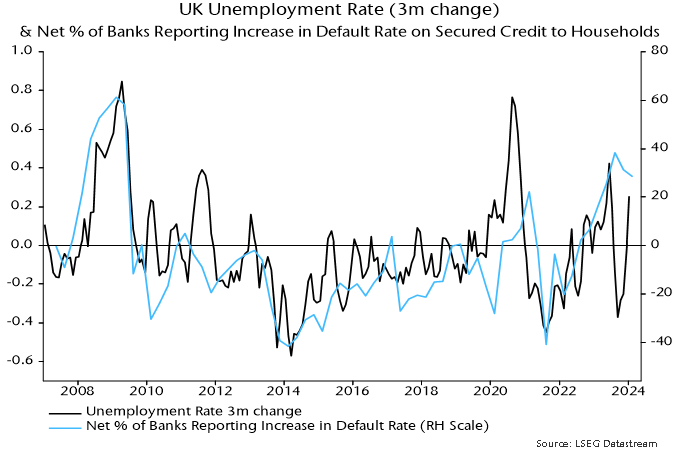

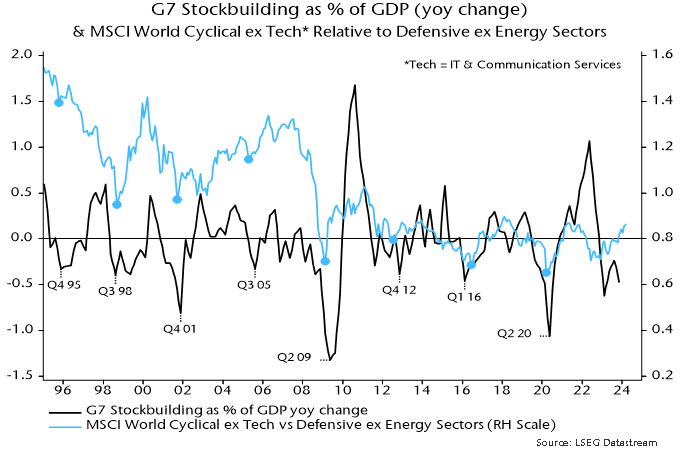

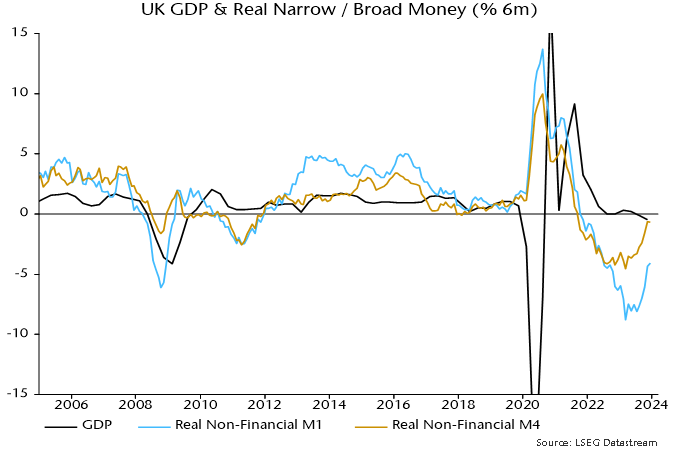

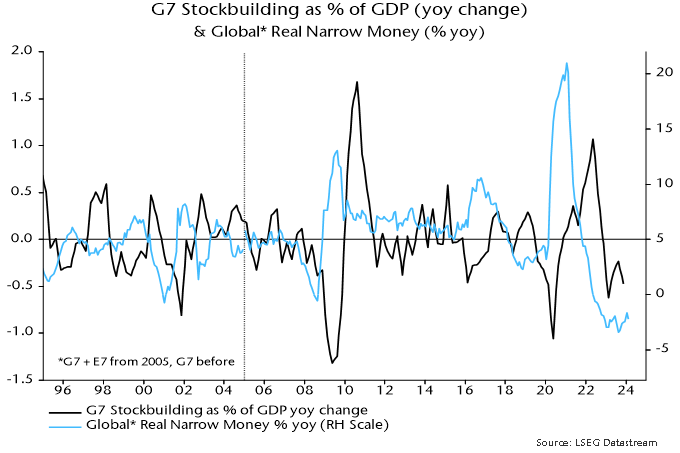

The key indicator used to monitor the cycle – the annual change in the stockbuilding share of G7 GDP – appears to have reached a major low in Q1 2023. A secondary indicator based on business surveys confirmed this trough in July – see chart 1.

Chart 1

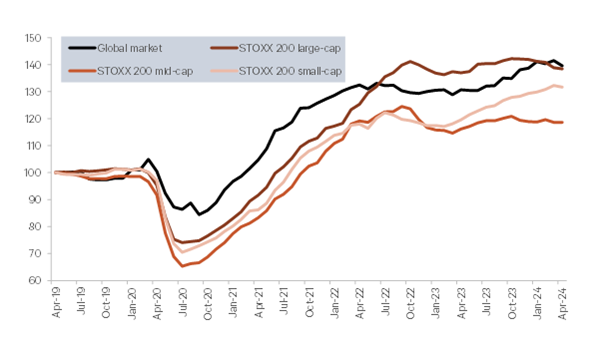

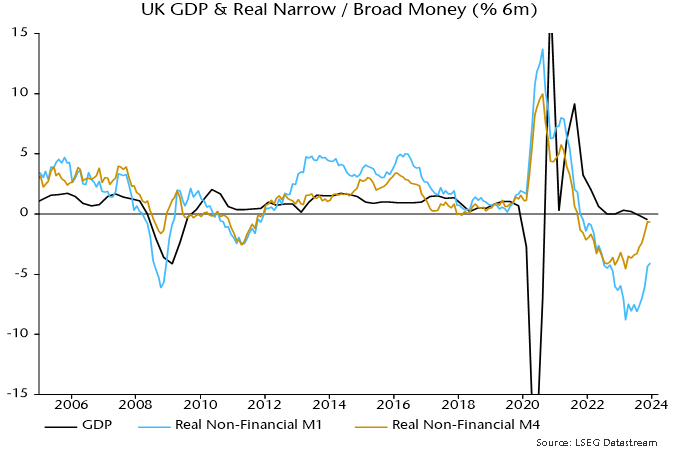

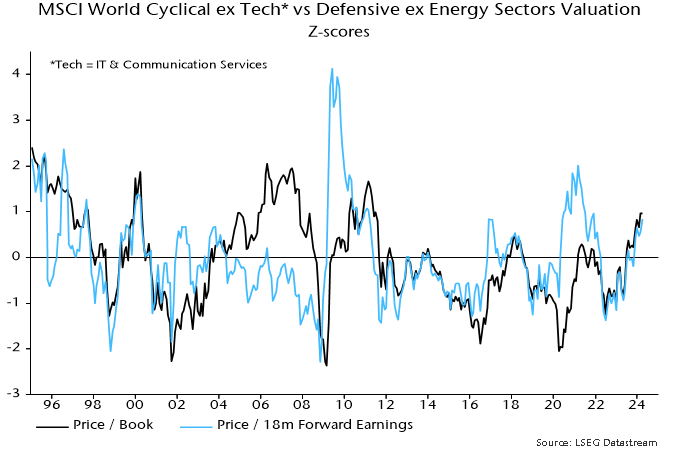

Stockbuilding cycle lows historically were usually associated with nearby major or minor lows in cyclical asset prices. Chart 2 shows the relationship with the relative performance of equity market cyclical sectors, excluding IT and communication services. A cyclical rally gathered pace from April 2023, consistent with a H1 cycle trough.

Chart 2

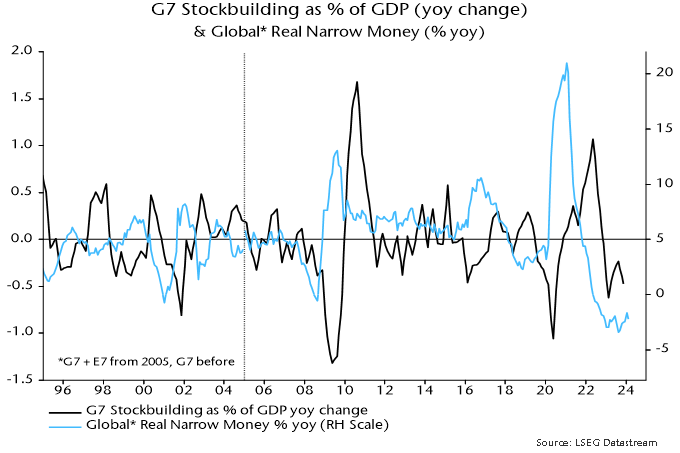

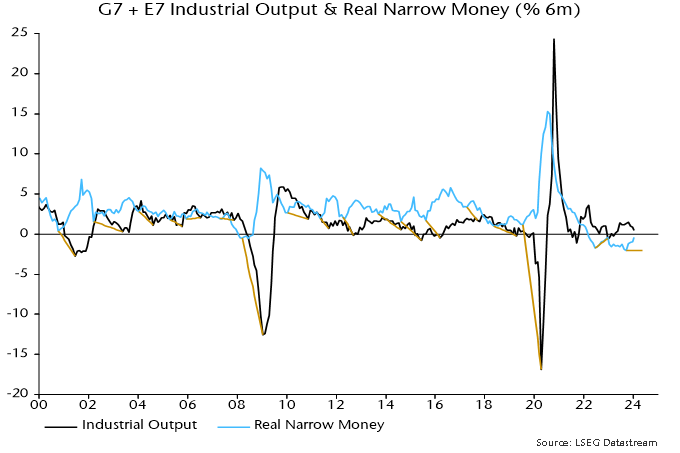

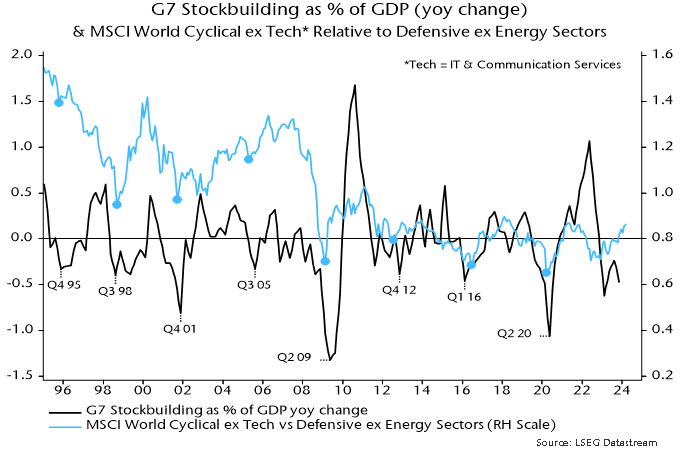

Why was a scenario anticipated in 2022 sadly underplayed in commentaries last year? The difficulty was that stockbuilding cycle lows historically were preceded by an upturn in global real narrow money momentum – chart 3. A marginal recovery in annual momentum occurred between February and June last year but a relapse to a lower low ensued. With no monetary improvement, and major central banks continuing to tighten into H2, it seemed unlikely that economic news and fund flows would support outperformance of cyclical assets.

Chart 3

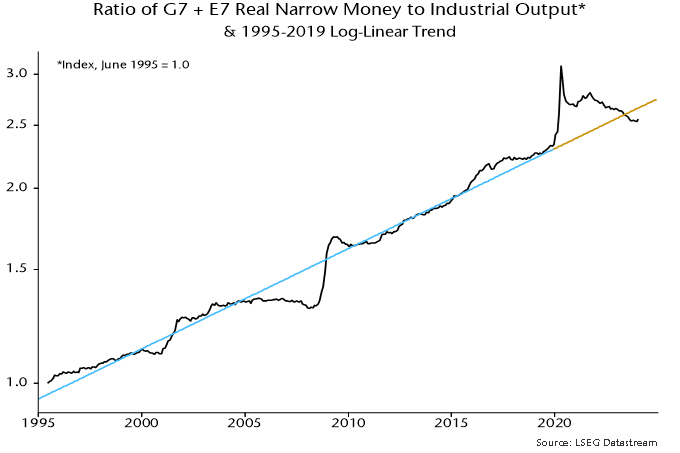

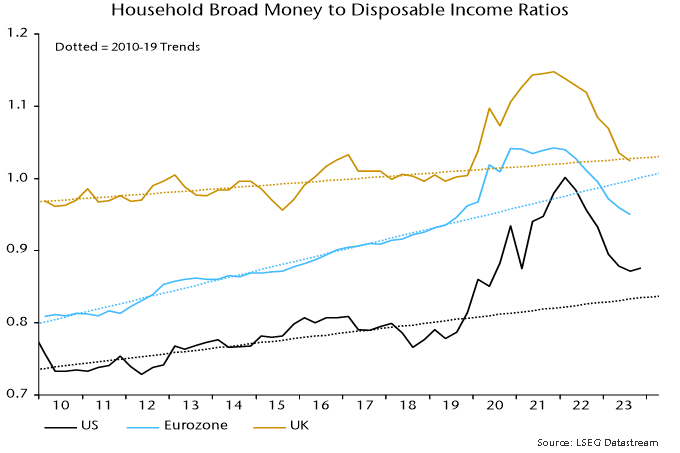

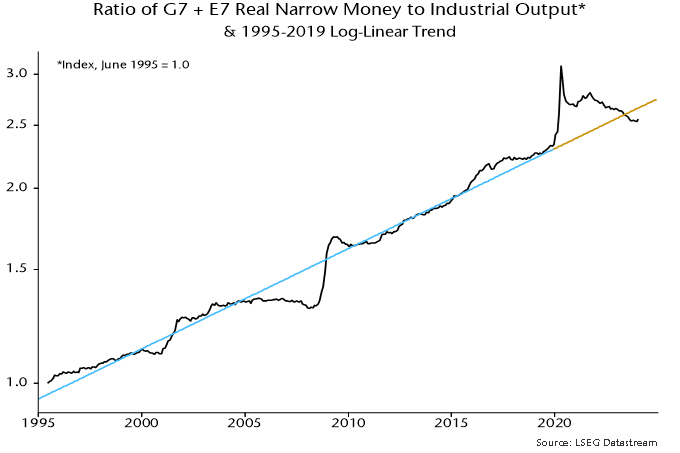

One explanation for the disconnect is that real money momentum, while a reliable indicator historically, failed to capture the availability of money to support activity and markets because of an overhang of “excess” balances created by earlier monetary strength. The ratio of the stock of global real narrow money to industrial output at end-2022 was still 4% above its steeply rising pre-pandemic trend – chart 4.

Chart 4

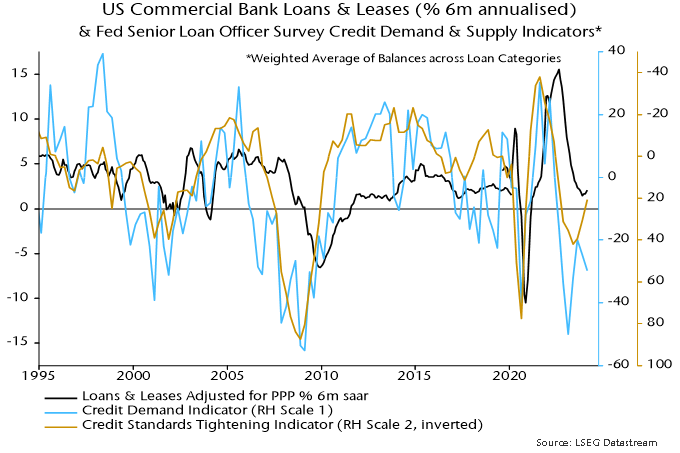

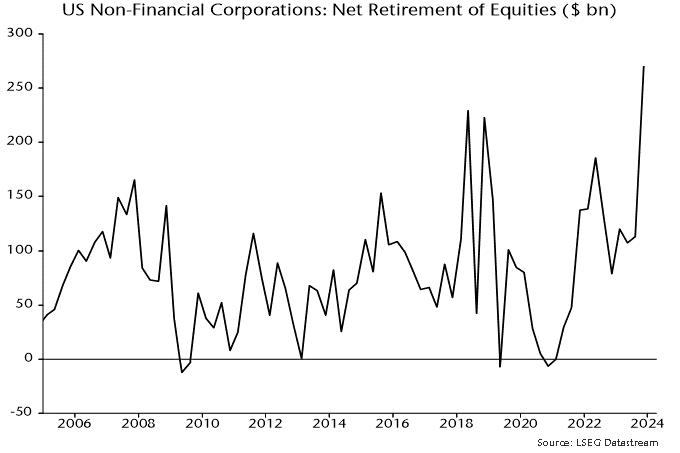

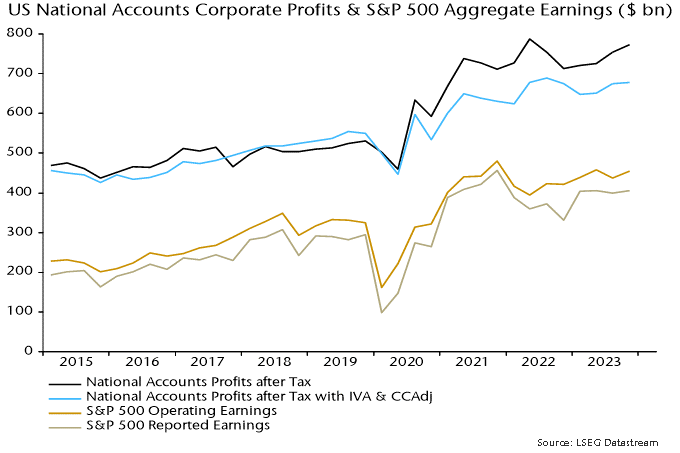

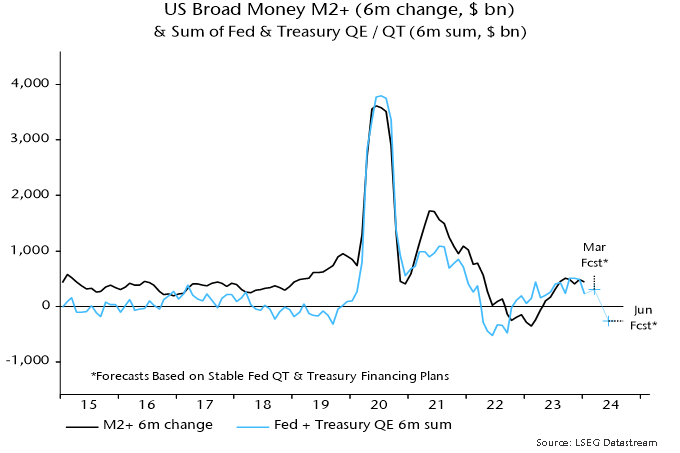

The strength of US equities may also have partly reflected the US Treasury’s decision, following the suspension of the debt ceiling in June, to “overfund” the federal deficit via issuance of bills, which were purchased mainly by money-creating institutions. This had the effect of more than offsetting the monetary drag from the Fed’s QT, while low coupon issuance created space in investors’ portfolios for additional purchases of credit and equities.

Support from these influences should be at or close to an end. The ratio of global real narrow money to industrial output returned to its March 2020 level in mid-2023, moving sideways since and now 4% below the pre-pandemic trend – chart 4. The Treasury’s financing plans, meanwhile, envisage a reduction in the bill float in Q2, raising the possibility of renewed monetary US weakness unless the Fed swiftly tapers QT.

Global real narrow money momentum has firmed again since Q3 2023 but remains negative, in both annual and six-month terms. A revival could, in theory, continue even if major central banks delay policy easing: rising economic confidence could be reflected in a switch out of time deposits and money funds into demand / overnight deposits, while EM money trends may improve further in response to recent policy easing. More likely, a normalisation of money growth will require a significant reversal of 2022-23 DM policy rate hikes.

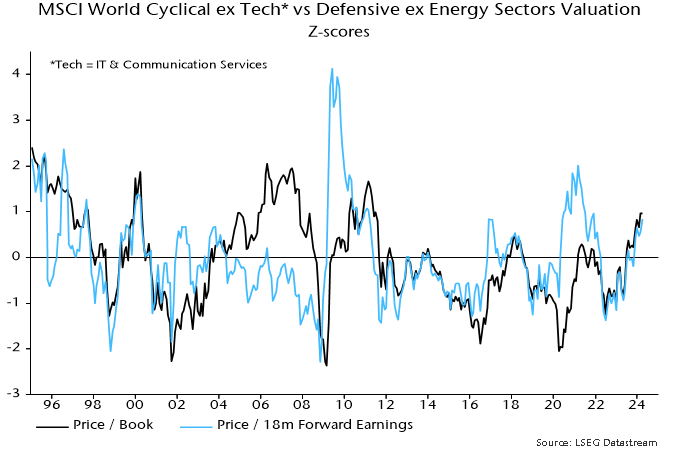

Without a further rise in real money momentum, the initial stockbuilding cycle recovery may prove disappointingly limp or even fizzle altogether, revisiting the H1 2023 low. Such a scenario would pose a major risk to some cyclical assets now apparently discounting solid / sustained economic growth, such as the DM cyclical equities sector basket – chart 5.

Chart 5

How could investors sharing the latter concern and favouring a defensive bias hedge against the possibility that a stockbuilding cycle upswing unfolds normally, implying economic acceleration into 2025? Some cyclical assets have lagged, including industrial commodity prices, the DM materials sector and EM cyclical sectors, which – unlike in DM – are at a low valuation versus defensive sectors relative to history.

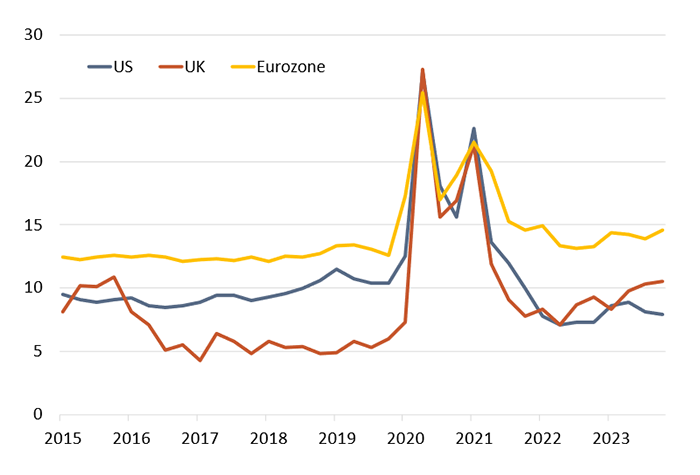

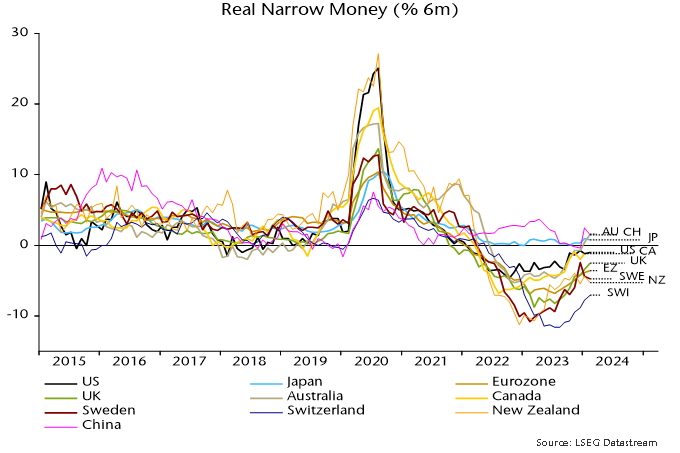

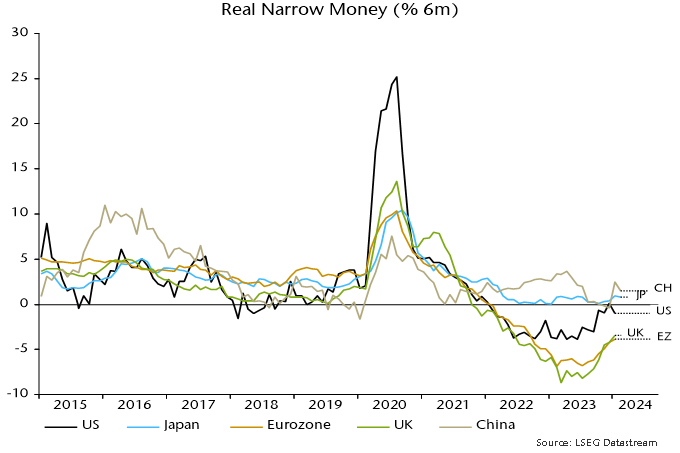

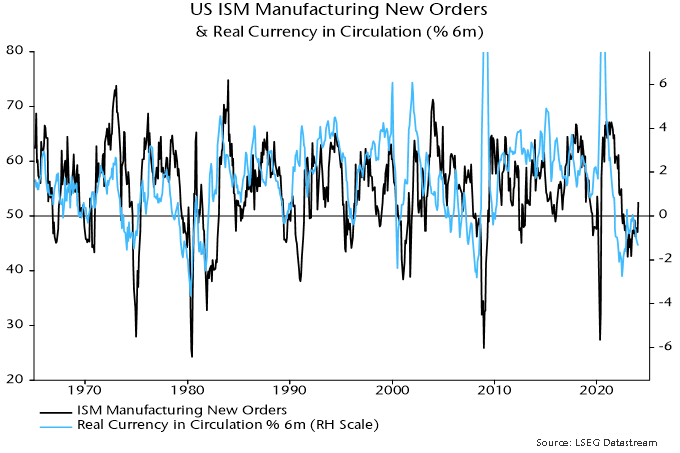

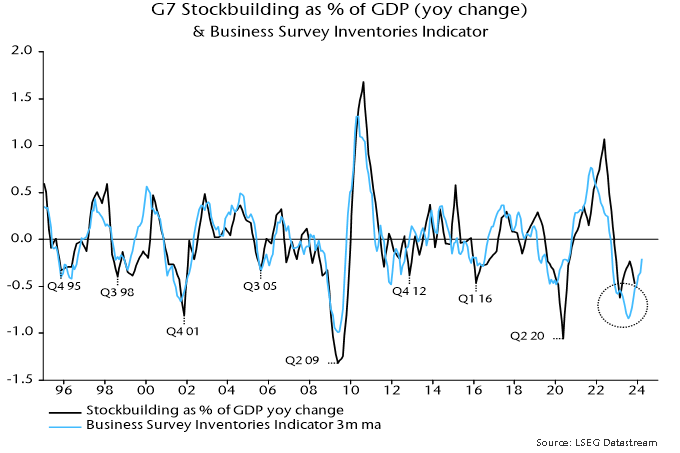

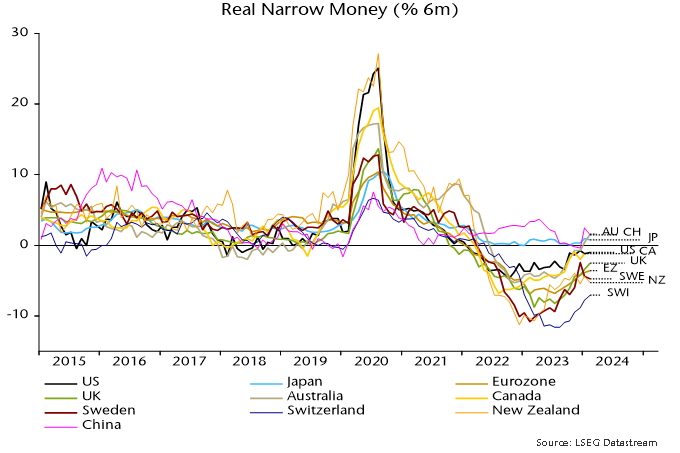

Chart 6 shows six-month real narrow money momentum in major countries. The US remains above Europe but the gap has narrowed, while, as argued above, the US recovery could go into reverse into Q2. The UK, meanwhile, has crossed above the Eurozone, suggesting improving relative economic prospects following GDP underperformance in the year to Q4.

Chart 6

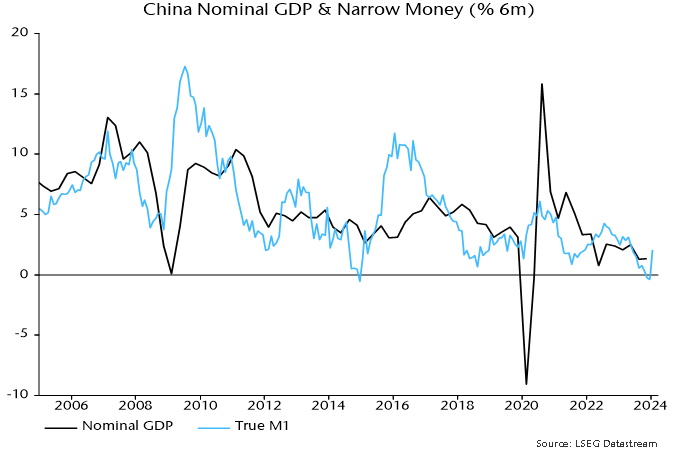

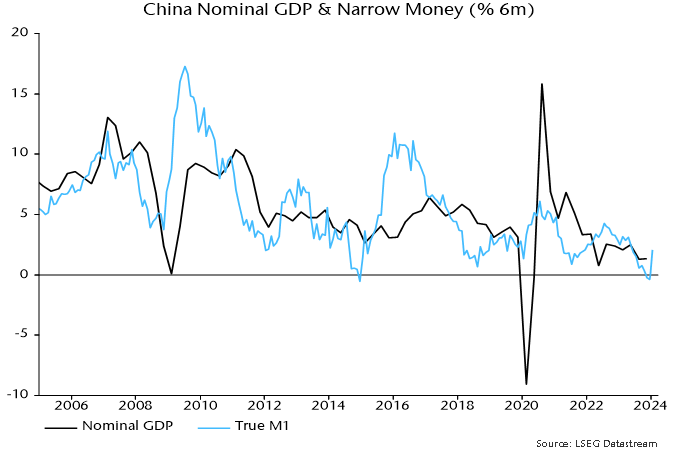

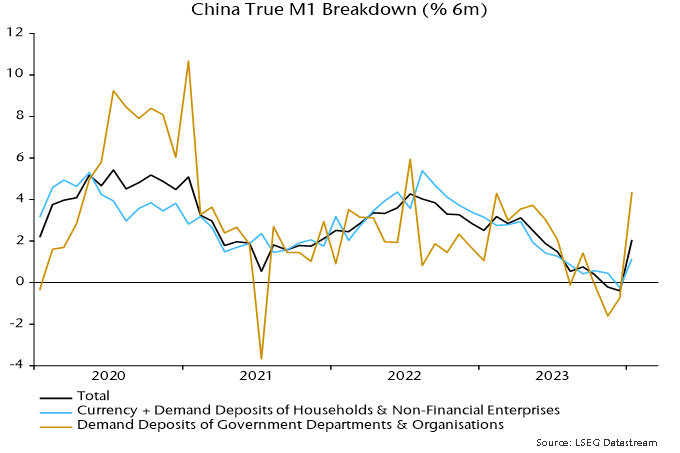

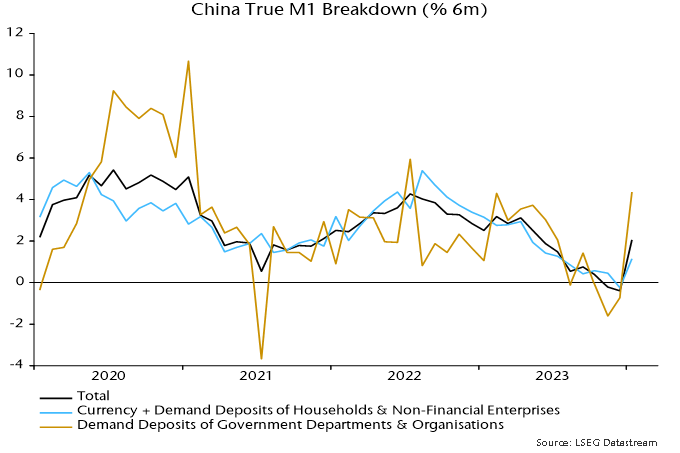

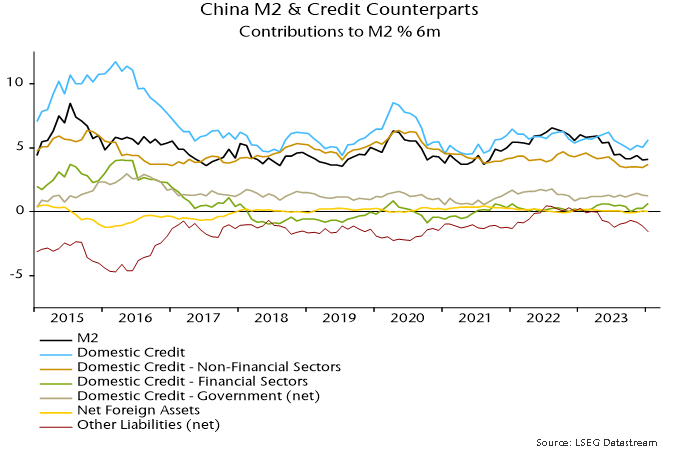

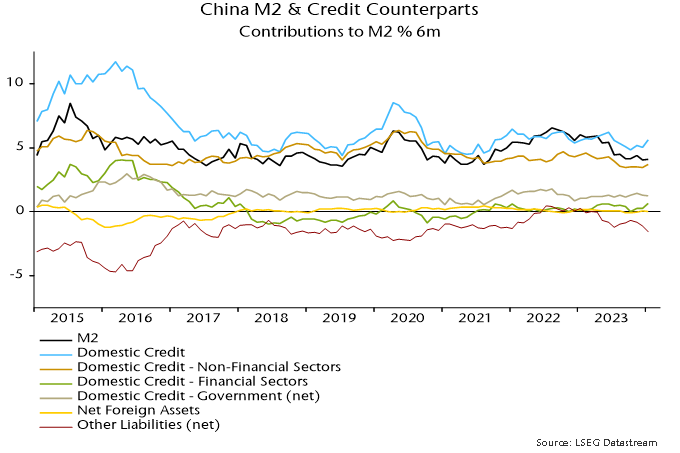

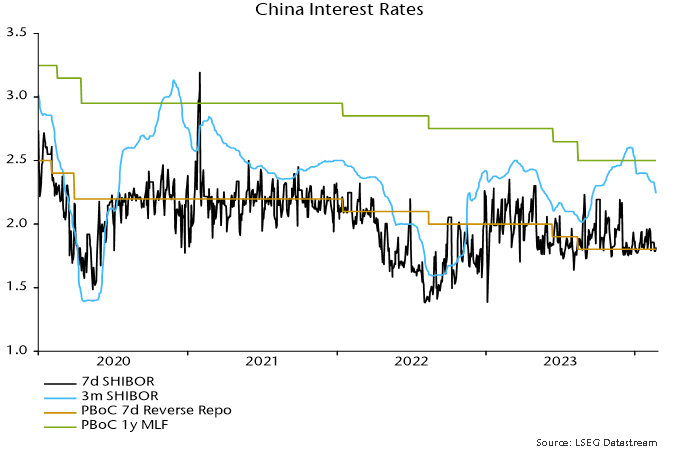

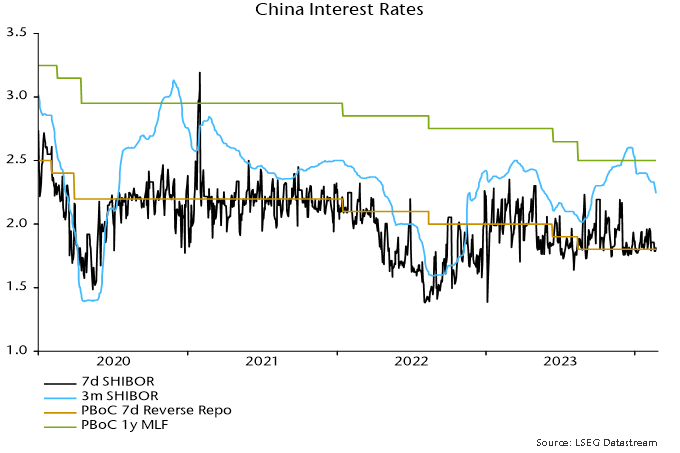

China was a significant contributor to the recent rise in global real narrow money momentum, following record PBoC lending to banks in Q4. Such lending, however, contracted in January / February and a decline in term money rates has stalled, raising concern that the recovery in money growth will falter.

Other notable features include a pick-up in Australia, continued relative weakness in Switzerland and a relapse in Sweden. The suggestion is that the Australian economy will outperform, delaying rate cuts; by contrast, the Swiss National Bank has already embarked on easing, with the Riksbank expected to follow in Q2.

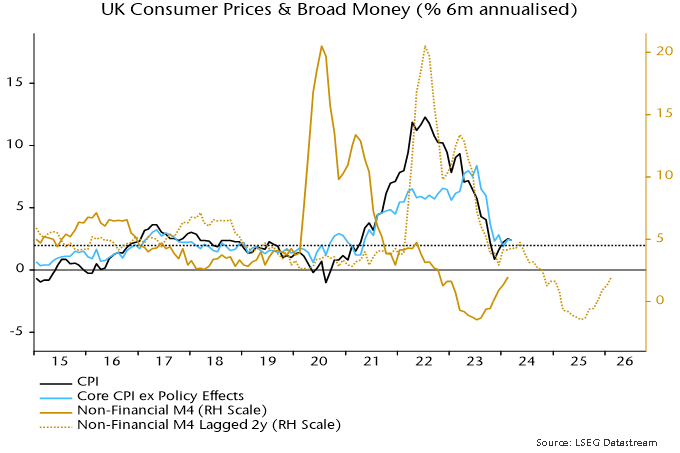

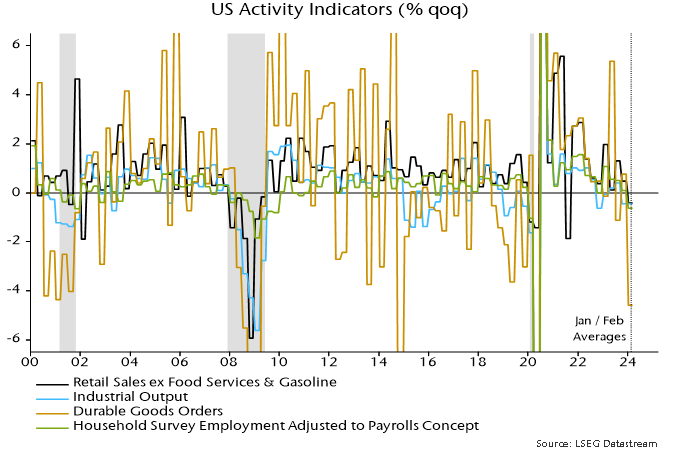

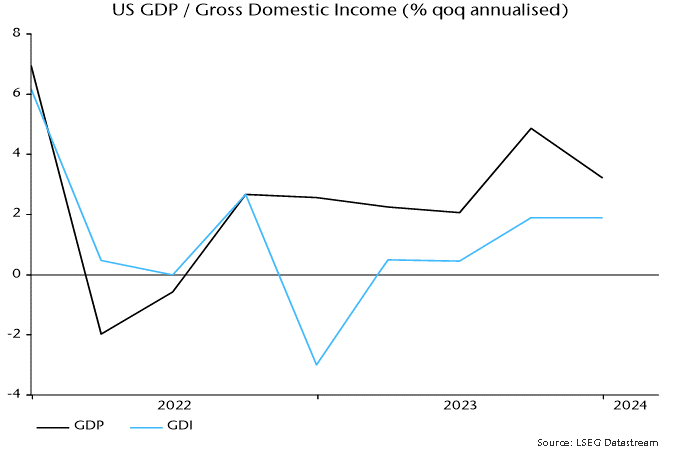

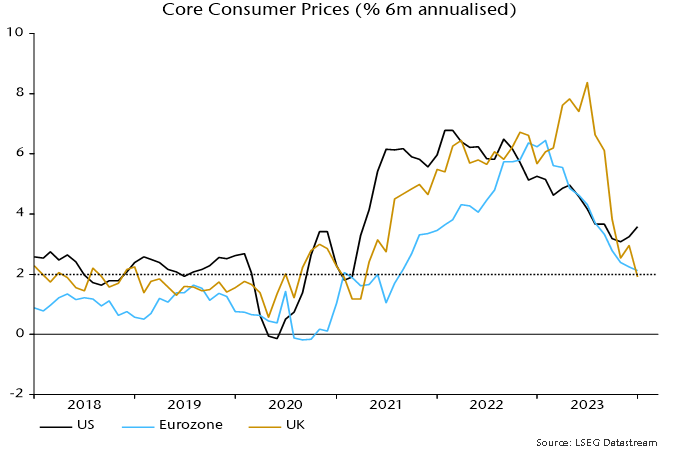

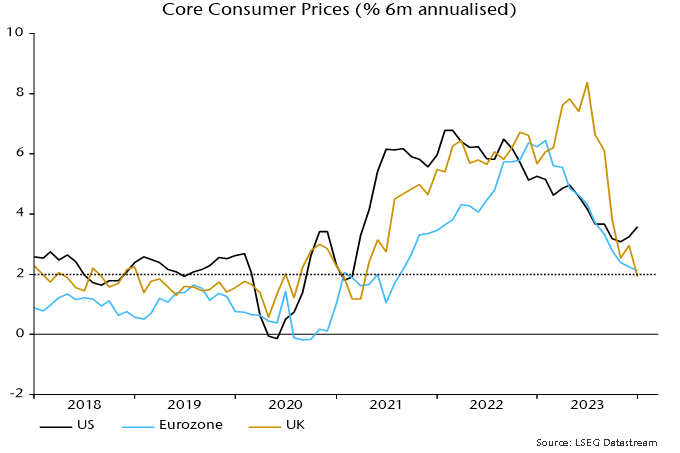

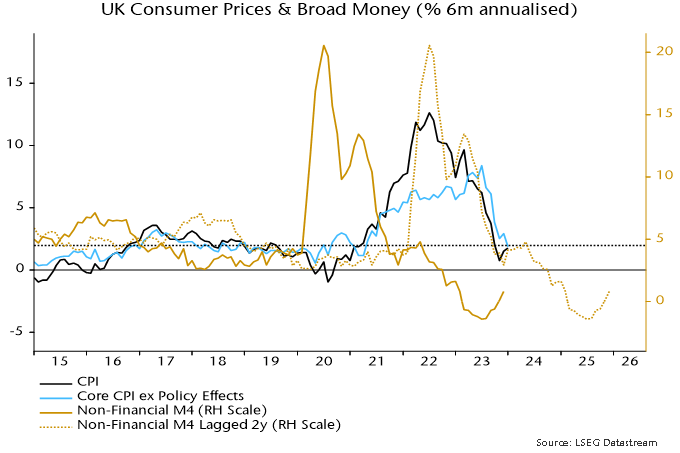

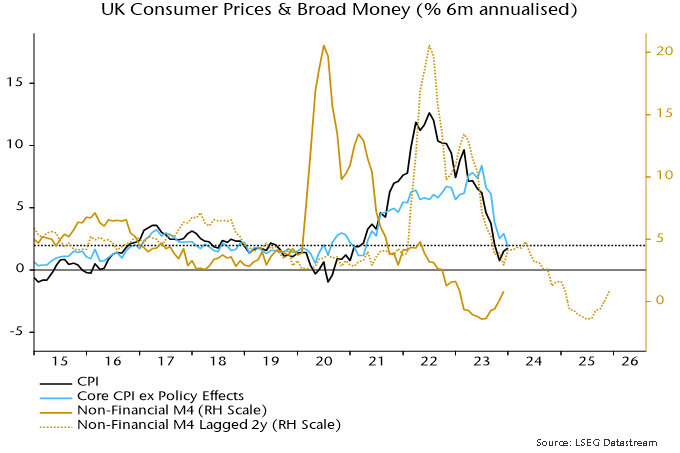

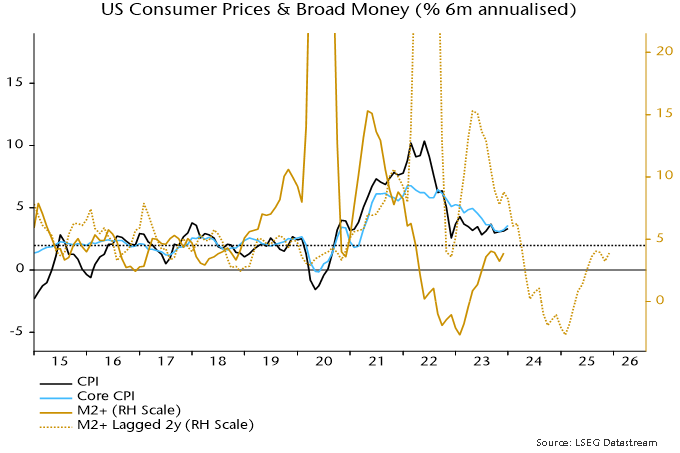

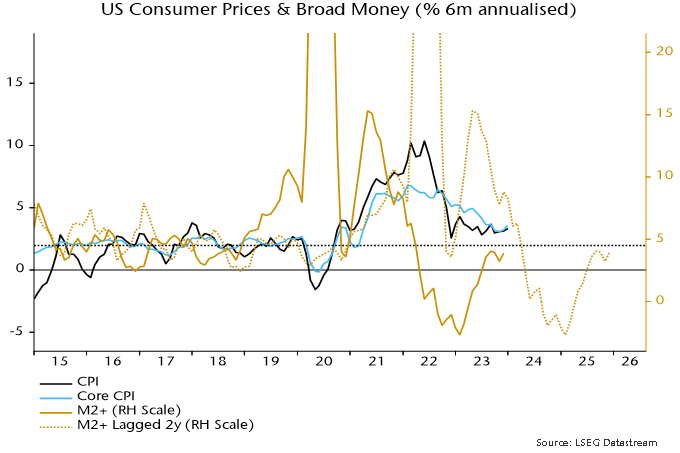

G7 inflation has continued to moderate in line with a simplistic monetarist forecast based on the profile of broad money growth two years earlier. A note in November 2022 suggested that annual consumer price inflation (GDP-weighted average), then at 7.8%, would fall below 3% by December 2023. The latest reading, for February, was 2.9%.

US annual core inflation on the Fed’s favoured PCE measure was 2.8% in February or 2.2% excluding lagging rents. Market concerns about inflation remaining “stubborn” are based on a rebound in shorter-term momentum measures but this has been mainly due to an outsized January gain, possibly reflecting residual seasonality (which could also explain unexpected weakness in late 2023), i.e. these measures are likely to fall back sharply as the January effect drops out.

G7 annual broad money growth continued to decline into April 2023, suggesting that the primary inflation trend will remain down into H1 2025. The reduction to date, however, was accelerated by post-pandemic normalisation of supply chains and weakness in commodity prices – the former effect is over and commodity prices usually rise during stockbuilding cycle upswings. The baseline view here remains that inflation rates will return to target by H2 2024 with significant risk of a subsequent undershoot and no sustained rebound before H2 2025.