Changes in household energy bills will cut 1.6 percentage points (pp) from UK annual CPI inflation between September and October, implying a drop from 6.7% to 5.1% if annual rates of increase of other components are unchanged. Slowing food prices promise to lop a further 1.5 pp off annual inflation by early 2024, both directly and via pass-through to the important catering services component. So a minimum expectation is that the headline rate will be back at about 3.5% by next spring, before allowing for likely moderation in other inflation components.

The energy bill effect in October reflects the dropping out of a 25% increase in October 2022 along with a 7% cut in the price cap this month. The annual rate of change will swing from 6% in September to -22%. A simple calculation would suggest a 1.3 pp impact on headline CPI inflation, i.e. the 28 pp swing multiplied by a published weight of 4.8%. It turns out that the actual impact is larger because of the way that monthly price changes have interacted with variations in the weight due to relative price movements and basket revisions.

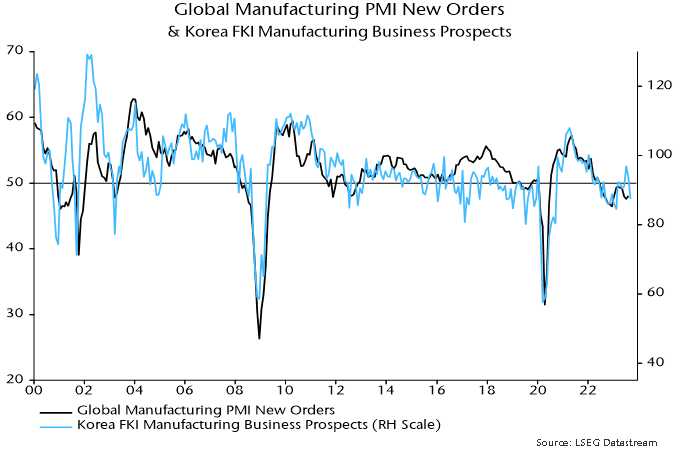

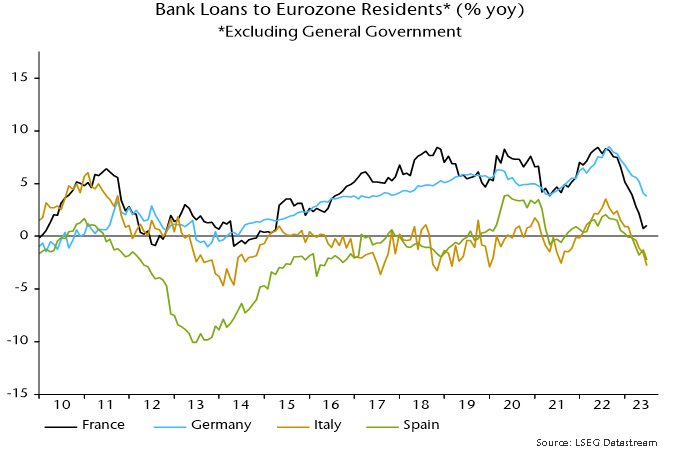

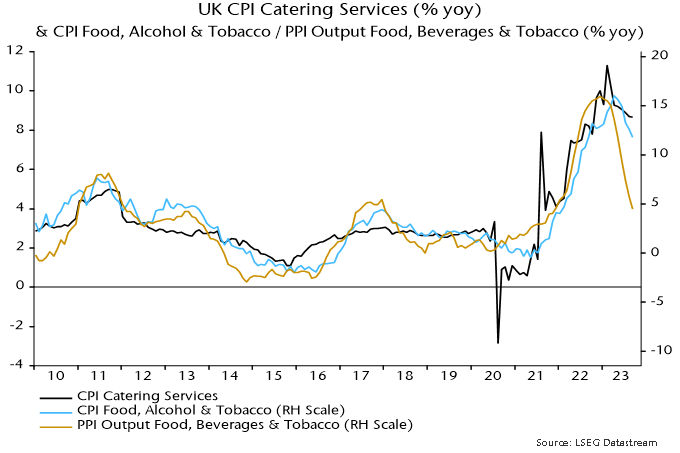

Annual inflation of food, beverages and tobacco has moderated but was still up at 11.8% in September. The CPI measure tracks the corresponding PPI component, annual inflation of which is now below 5% (4.5% in September) – see chart 1.

Chart 1

A fall in annual inflation of the CPI food measure to 5% by early 2024 would suggest a 1.1 pp impact on the headline rate, i.e. the 6.8 pp fall from the September multiplied by a published weight of 16.1%*.

As the chart shows, however, food prices are also a key driver of the catering services component, which has a 10.9% weight. The beta of this component to food prices has been about 0.5 historically, i.e. the suggested fall of 6.8 pp in annual food inflation would be expected to lower catering services inflation by 3.4 pp, cutting a further 0.4 pp from the headline rate.

Central bankers and commentators worried about sticky services inflation underestimate the pass-through effects of energy and food prices. Catering services accounts for 23.4% of the services basket, so the suggested 3.4 pp drop in the annual increase would cut 0.8 pp from annual services inflation (6.9% in September).

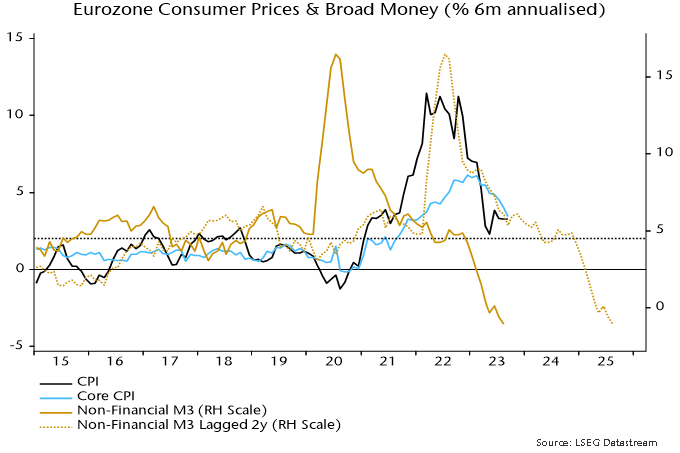

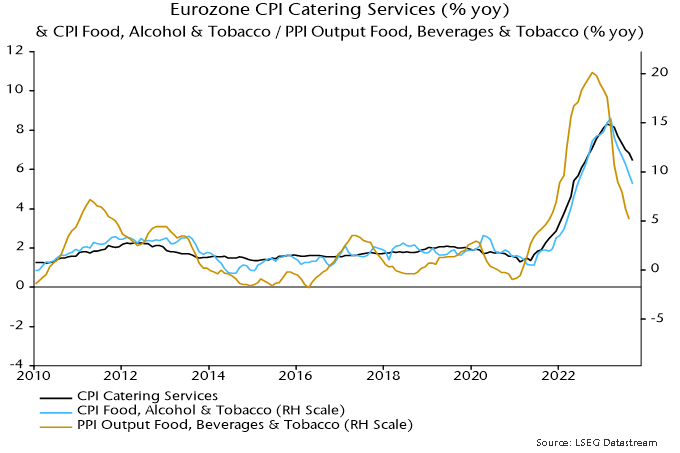

The above analysis also applies to the Eurozone, although the estimated impacts are smaller because annual inflation of food, beverages and tobacco is lower than in the UK, i.e. 8.8% versus 11.8% in September.

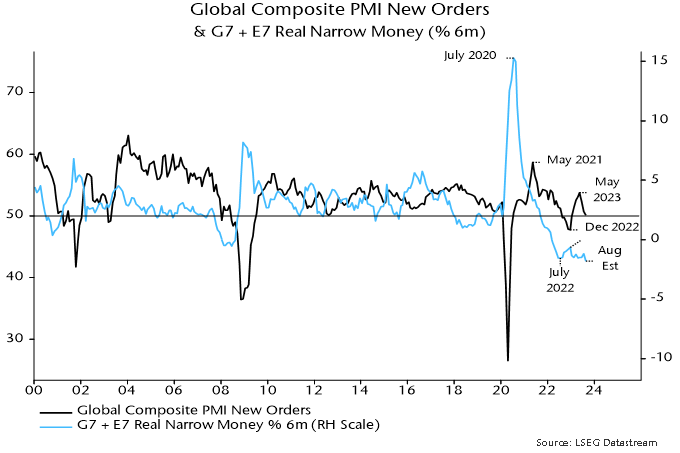

As in the UK, a slowdown in the corresponding PPI component suggests a fall in annual food inflation to 5% soon – chart 2. A 3.8 pp reduction would imply a 0.8 pp cut in headline inflation, based on a 20.0% weight.

Chart 2

Eurozone catering services inflation also has a beta of about 0.5 to food prices, so could fall by 1.9 pp. This would cut a further 0.2 pp from the headline rate and 0.4 pp from services inflation (based on weights of 8.4% and 19.2% in the overall and services baskets respectively).

So the combined direct and indirect effects of the food slowdown on CPI inflation would be about 1.0 pp in the Eurozone against 1.5 pp in the UK.

*As with the energy effect, a detailed calculation yields a slightly larger impact.