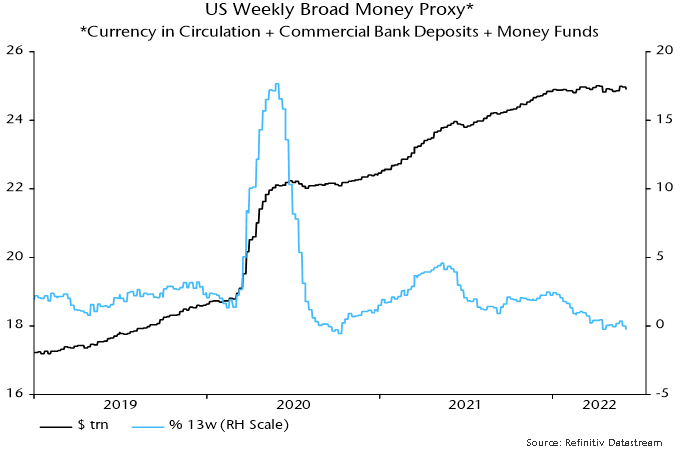

US broad money growth has slowed significantly despite a strong pick-up in bank lending expansion. How has this occurred and does lending strength portend a rebound in money growth?

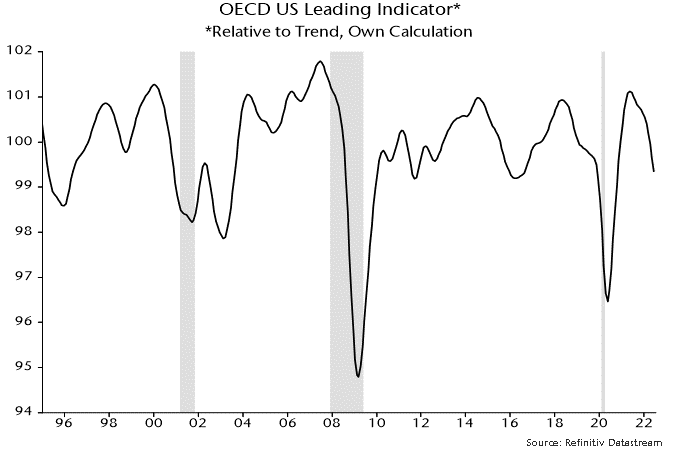

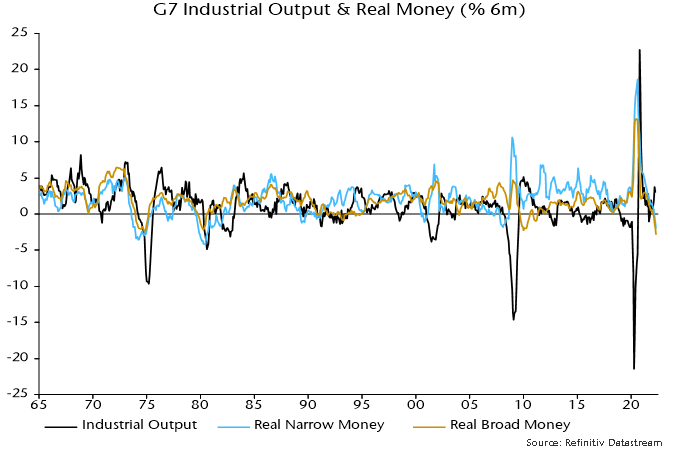

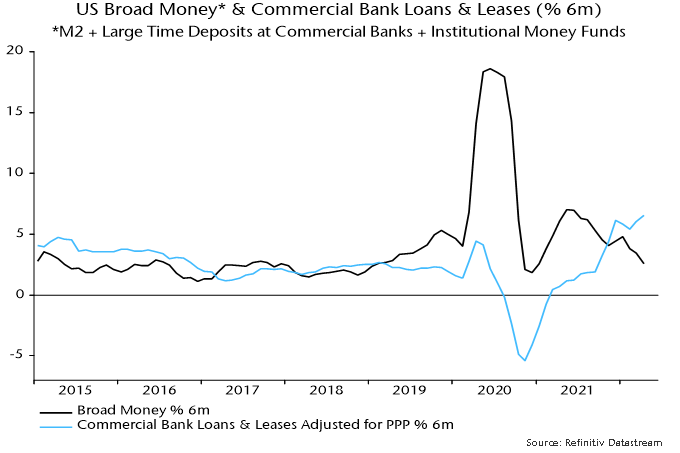

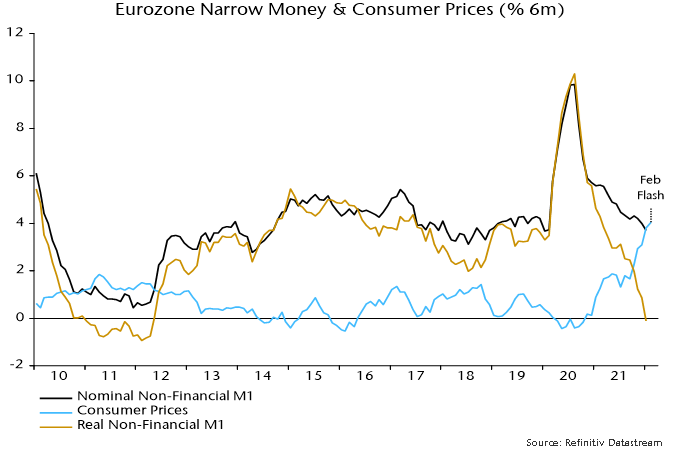

The broad money aggregate calculated here* rose by 2.6% (5.2% annualised) in the six months to April, down from 4.5% (9.2%) in the prior six months – see chart 1. All the growth over the last six months occurred over November-January: the aggregate has flatlined over the last three months.

Chart 1

The monetary slowdown contrasts with further strength in bank lending. Commercial bank loans and leases, adjusted for Payment Protection Program forgiveness, grew by 6.5% (13.5% annualised) in the six months to April, up from 3.3% (6.6%) in the previous six months.

Q. What happened to the additional deposit money created by the expansion of banks’ loan books?

A. It was mostly diverted into the coffers of the US Treasury.

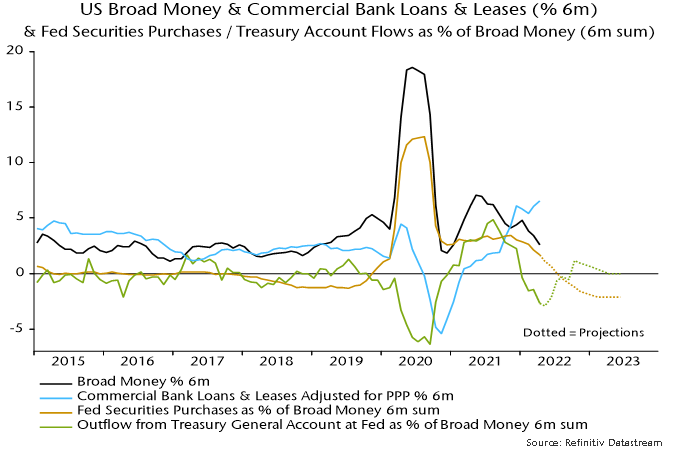

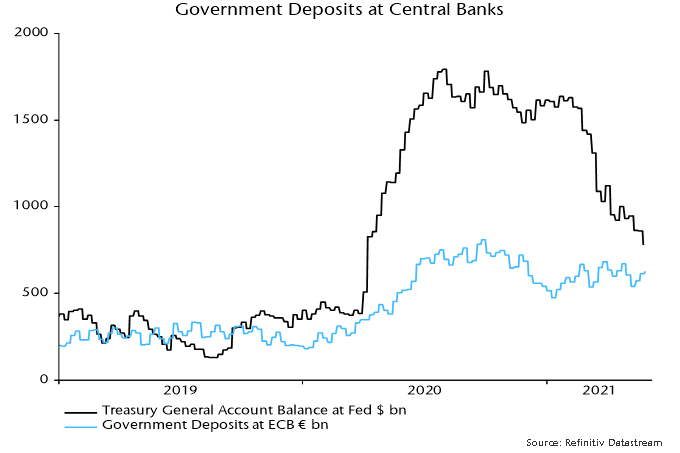

Political wrangling over raising the debt ceiling resulted in the Treasury running down its cash balance at the Fed from over $800 billion in mid-2021 to below $100 billion by December. This monetary injection boosted broad money growth late last year.

Since the ceiling was raised in December, the Treasury has “overfunded” the federal deficit to replenish its cash balance, which currently stands at over $900 billion.

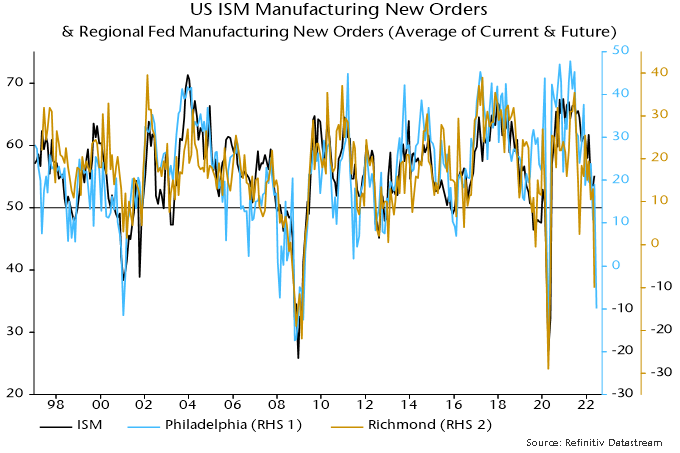

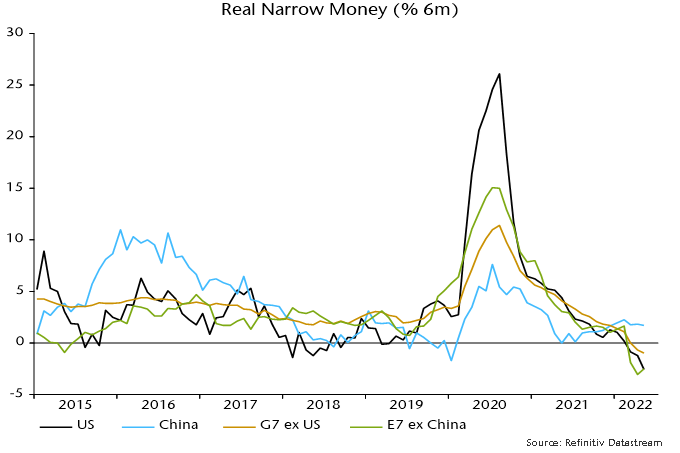

The monetary inflow to the Treasury amounted to 2.7% of broad money in the six months to April – chart 2.

Chart 2

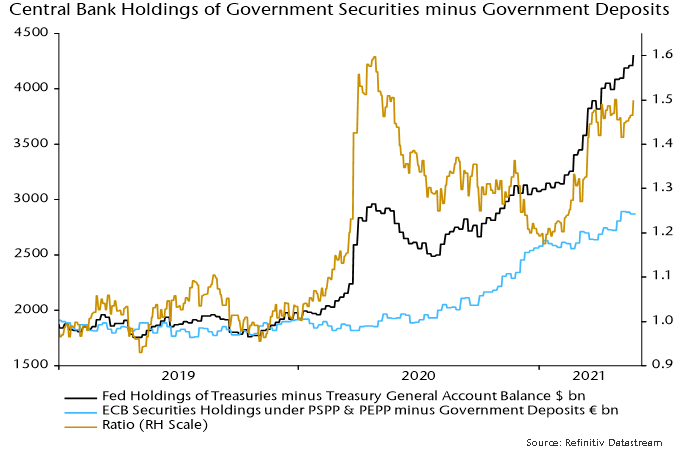

The monetary slowdown has also reflected – to a lesser extent – the wind-down of QE: securities purchases by the Fed were 1.7% of broad money in the six months to April, down from 3.4% in the prior six months.

Adding together the effects of QE and changes in the Treasury’s cash balance, there was a net monetary withdrawal of 1.0% of broad money in the six months to April, following an injection of 6.2% in the previous six months. This reversal more than offset the monetary impact of stronger bank lending expansion.

What happens next?

The Treasury’s latest financing projections assume a cash balance of $650 billion at end-September, representing a fall of about $310 billion from its level at end-April.

The Fed, meanwhile, plans to reduce its securities holdings at a monthly pace of $47.5 billion starting in June rising to $95 billion in September. This suggests cumulative QT of about $330 billion over the six months to October.

In combination, QT and changes in the Treasury’s cash balance may, therefore, result in a net monetary withdrawal of only about $20 billion, or 0.1% of broad money, in the six months to October, down from $280 billion or 1.0% in the six months to April.

In terms of the combined influence of the Treasury and Fed, QT effectively started in January and is about to slow temporarily before stepping up later in the year – assuming no further change in the Treasury’s cash balance beyond the expected fall to $650 billion and an ongoing $95 billion per month reduction in the Fed’s securities holdings.

Will a temporarily reduced “public sector” drag allow broad money growth to recover into H2?

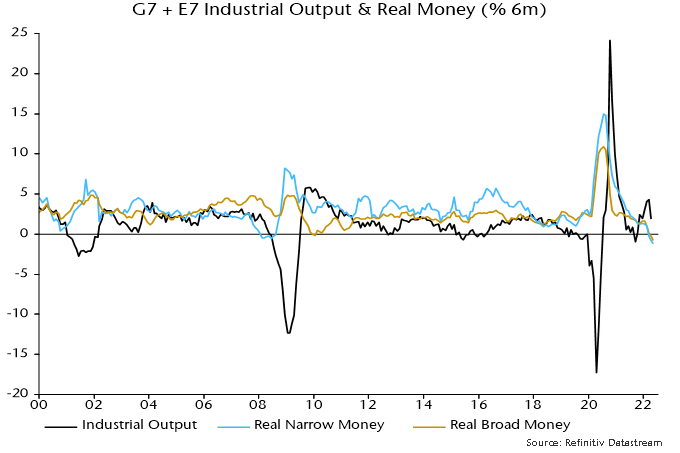

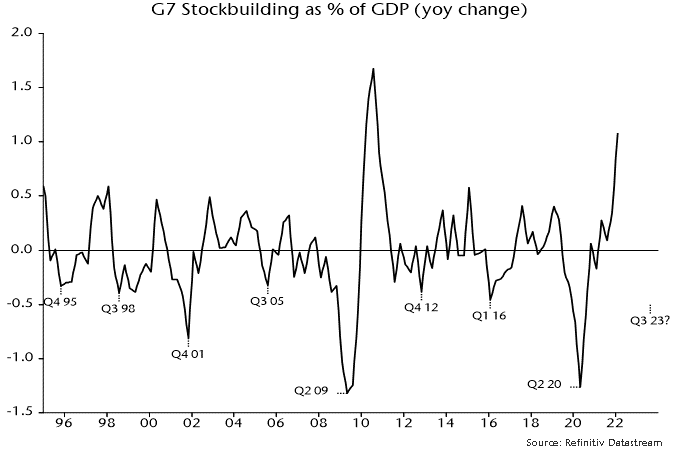

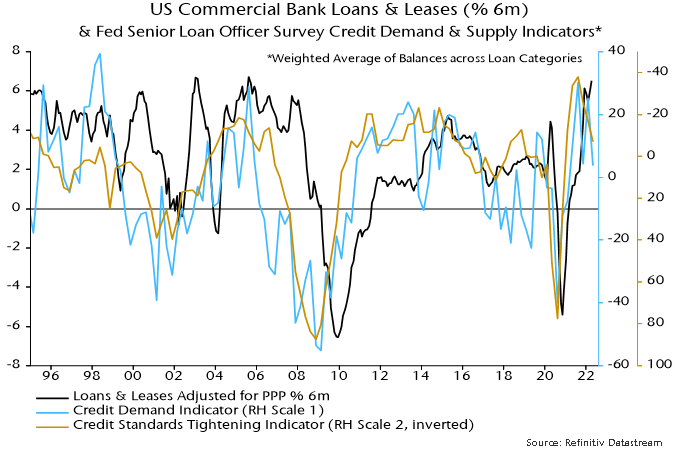

The forecast here is that this small positive will be outweighed by a slowdown in bank lending. Corporate credit demand has been boosted by inventory financing but the stockbuilding cycle is now entering a downswing. Higher mortgage rates will cool demand for real estate loans, while banks may rein back on consumer lending as economic prospects deteriorate.

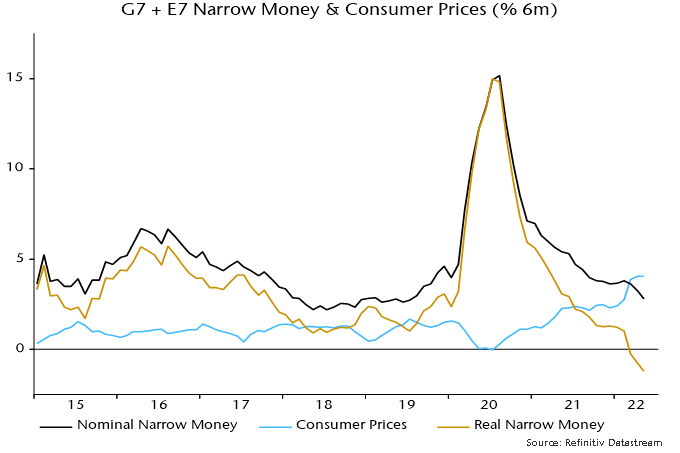

The suggestion of a lending slowdown is supported by the April Fed senior loan officer survey: the aggregate credit demand indicator fell sharply while the net percentage of banks tightening loan standards rose for a third successive quarter – chart 3.

Chart 3

*”M2+” = M2 + large time deposits at commercial banks + institutional money funds. M2 = currency + demand deposits + other liquid deposits + small time deposits + retail money funds. April estimated.