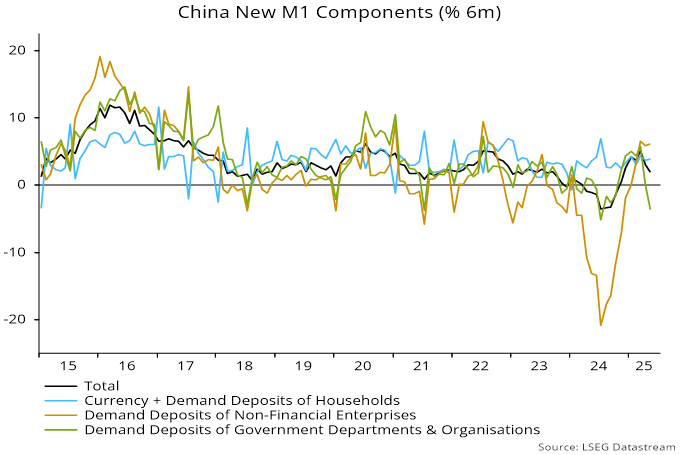

The latest signal from monetary data is that global economic momentum will inflect weaker from around late 2025. Cyclical considerations suggest that this will mark the beginning of a sustained downswing into 2027.

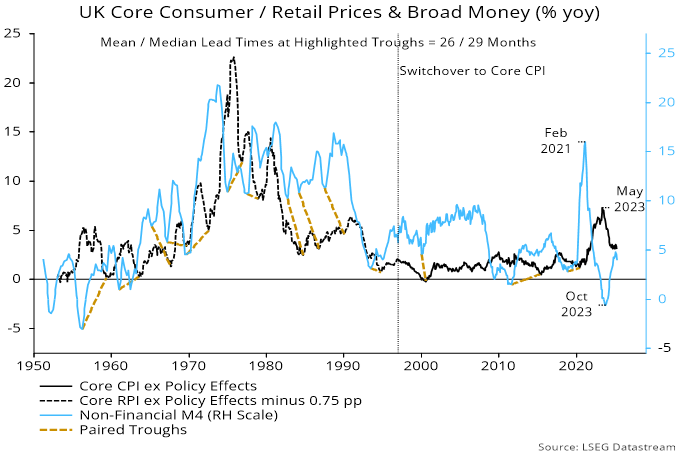

Lagged money trends argue that underlying inflation will fall further and remain low through 2026. Nevertheless, central banks may be slow to offset economic weakness with additional policy stimulus because of concerns about tariff effects and fiscal indiscipline, as well as scarring from the 2021-22 inflation surge.

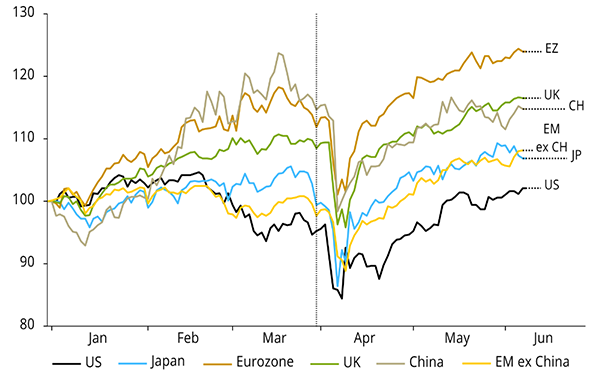

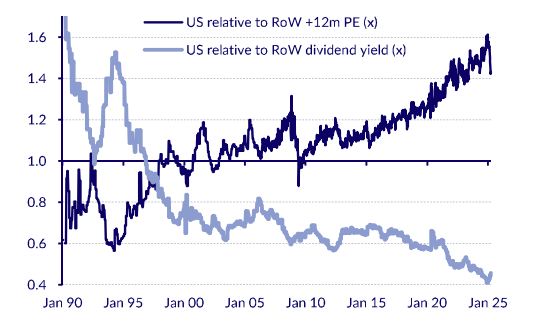

The suggestion is that equity markets face rising headwinds, with another sustained bull phase unlikely before 2027, when key cycles are scheduled to bottom. An appropriate strategy may be to underweight markets where monetary trends are relatively weak – Japan and the UK currently – while overweighting sectors with lower earnings sensitivity to expected cyclical weakness.

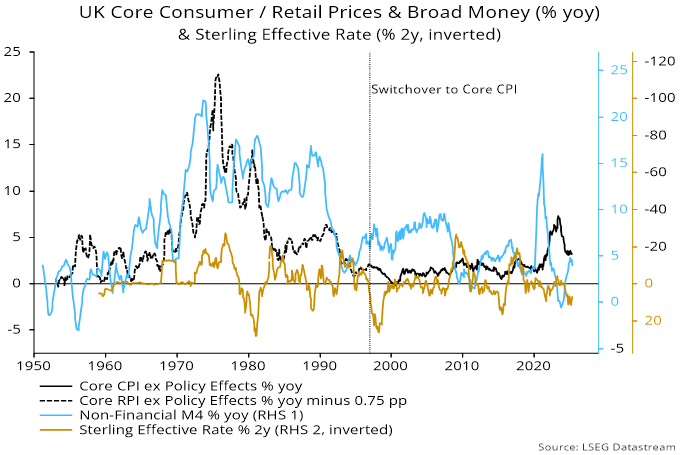

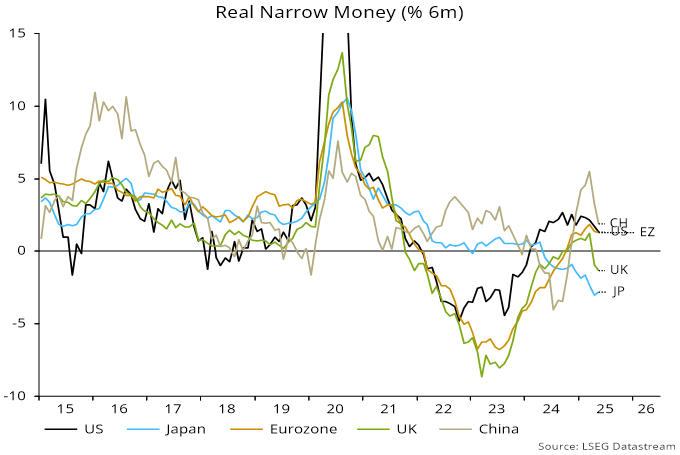

Elaborating on the above, global six-month real narrow money momentum – a key leading indicator in the approach followed here – reached a local high in March, falling sharply in April / May – see chart 1.

Chart 1

The rise from October 2024 into March suggested that the global economy would regain some momentum from around mid-2025, based on the recent average lag. A June rise in manufacturing PMI new orders could mark the start of such a shift, although results from national (as opposed to S&P Global) surveys were mixed. Still, April / May monetary weakness argues that any near-term recovery will be short-lived, with economic indicators likely to deteriorate again from around late 2025 – chart 2.

Chart 2

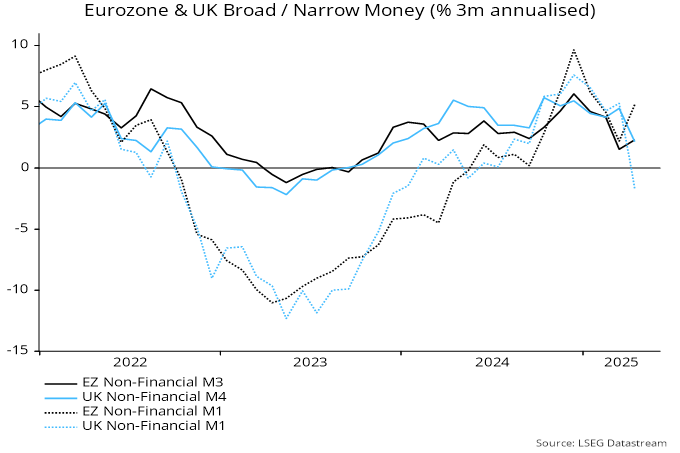

The latest fall in real money growth has been broadly based across countries, reinforcing the negative signal. Momentum is notably weak in Japan and the UK, arguing for economic underperformance. Eurozone growth has held up but hasn’t yet crossed above the US, cautioning against “europhoria” – chart 3.

Chart 3

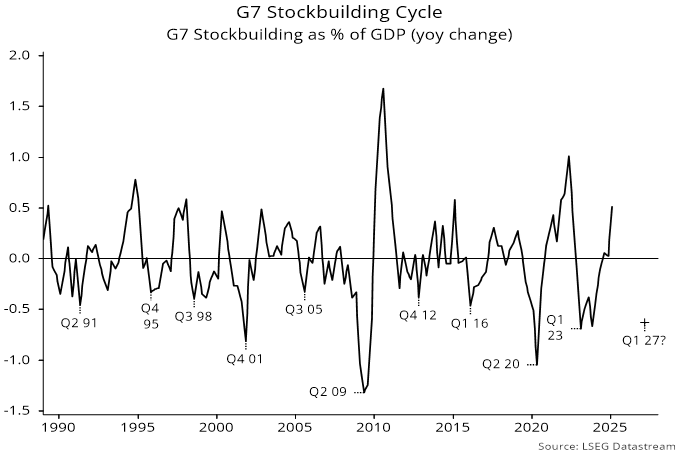

From a cyclical perspective, the stockbuilding cycle is in the window for a peak in terms of both time since the last low (Q1 2023) and the contribution of inventory accumulation to annual G7 GDP growth – chart 4. The latter has been boosted by front-loading to avoid tariffs, which appears to have continued in Q2.

Chart 4

The cycle should turn down by early 2026 at the latest and the baseline assumption here remains for a low in H1 2027, implying that the current cycle will be slightly longer than the 3.5 year historical average, balancing a shorter-than-average prior cycle. Stockbuilding cycle downswings are usually associated with significant slowdowns (or worse) in global economic growth and underperformance of risk assets.

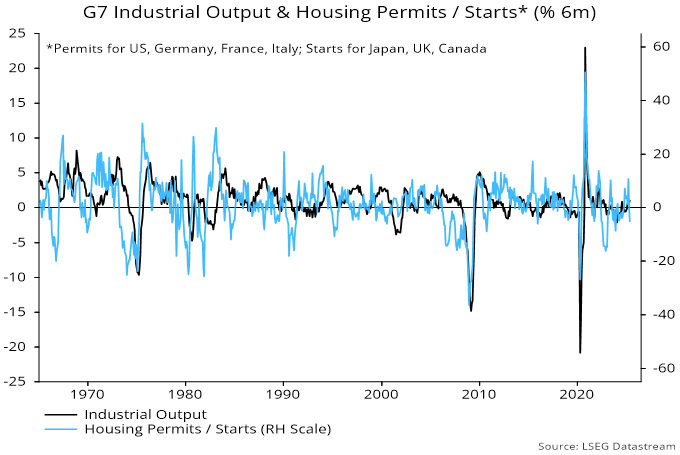

A key question is whether the coming downswing will be accompanied by weakness in the housing and / or business investment cycles, in which case a 2026-27 recession becomes the baseline. A housing downturn is more likely, given the maturity of the current cycle (16 years versus an 18-year average) and downward pressure from elevated longer-term interest rates. The business investment cycle is less advanced (year five versus a nine-year average), with corporate financial balances still healthy and AI deployment providing a tailwind.

Close attention, therefore, should be paid to housing indicators. The six-month rate of change of G7 housing permits / starts recently turned negative, suggesting a darkening outlook – chart 5.

Chart 5

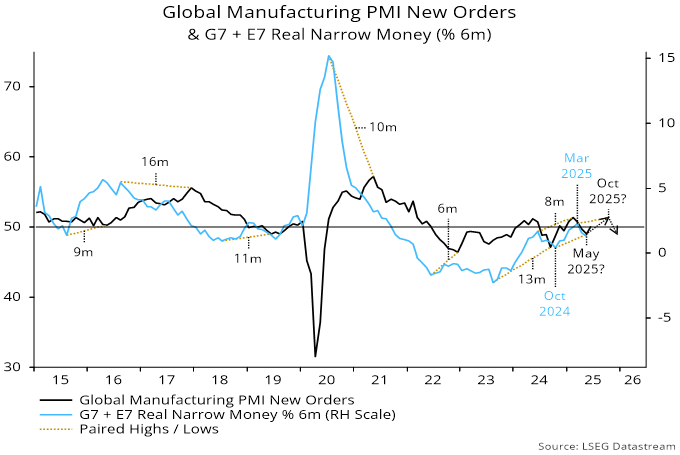

Inflation follows money growth with a roughly two-year lag, according to the simplistic monetary rule, which outperformed every other forecasting approach in 2021-22. Annual broad money growth bottomed in mid-2023 in the G7 and a year later globally, with limited subsequent recoveries. The suggestion is that underlying inflation will fall further and remain low through 2026.

On the analysis here, therefore, central banks could limit economic weakness by delivering timely additional policy stimulus while still meeting, or even undershooting, their inflation objectives. The US Fed, however, may continue to drag its feet amid uncertainty about near-term tariff effects and counterproductive political pressure, with a knock-on effect on the pace of easing elsewhere.

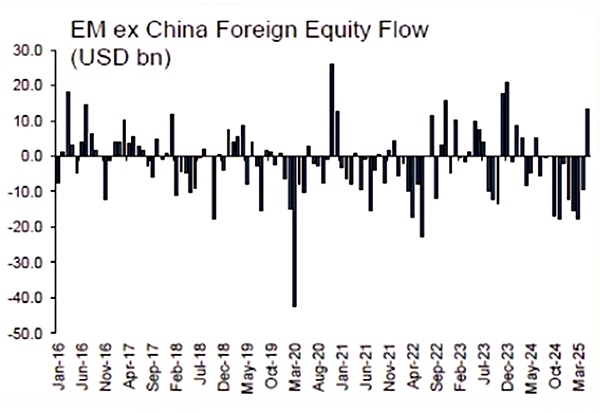

Both global “excess” money flow indicators used here to assess equity market prospects are currently negative, having been mixed three months ago. Specifically, global six-month real narrow money momentum has crossed back below industrial output momentum, while 12-month real money momentum remains beneath its long-run average – chart 6.

Chart 6

The indicators were misleadingly negative in 2023-24 because of a stock overhang resulting from the 2020-21 money growth surge. The assessment here is that there is no longer any excess relative to current levels of nominal GDP and asset prices.