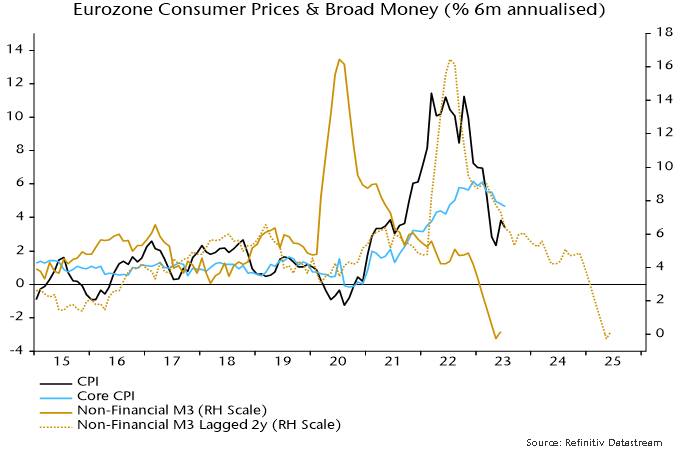

Eurozone CPI numbers for July were deemed disappointing because annual core inflation – excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco – stalled at 5.5%.

Or did it? The annual rise in the ECB’s seasonally adjusted core series slowed to 5.3%, below the consensus forecast of 5.4% for the Eurostat unadjusted measure. The two gauges rarely diverge to this extent (they both recorded 5.5% inflation in June).

The six-month rate of increase of the ECB series eased to 4.7% annualised in July, the slowest since June 2022 and down from a December peak of 6.2%. Six-month headline momentum was lower at 3.4%.

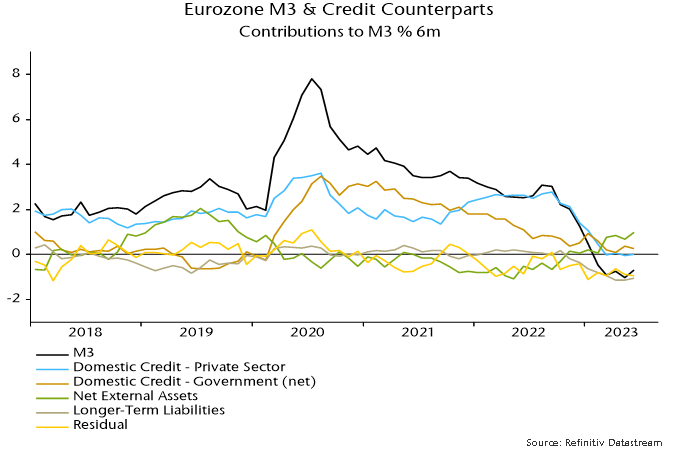

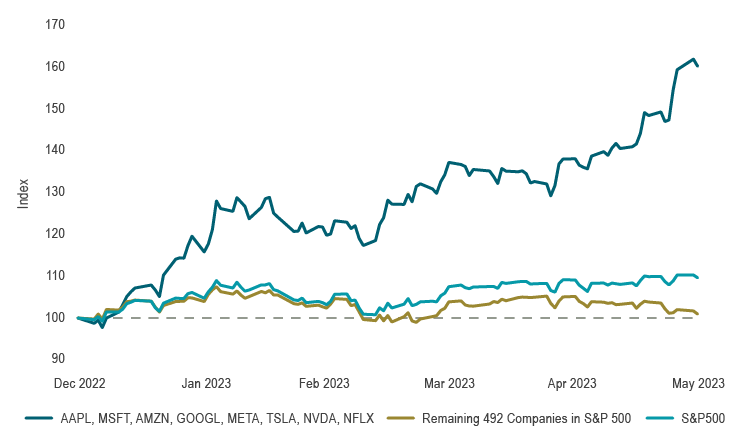

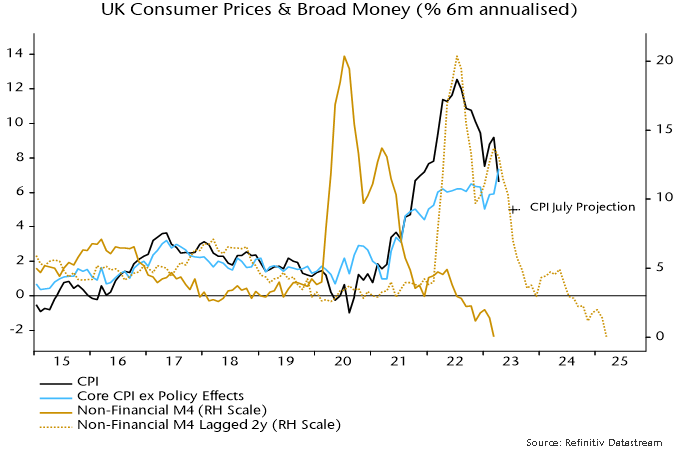

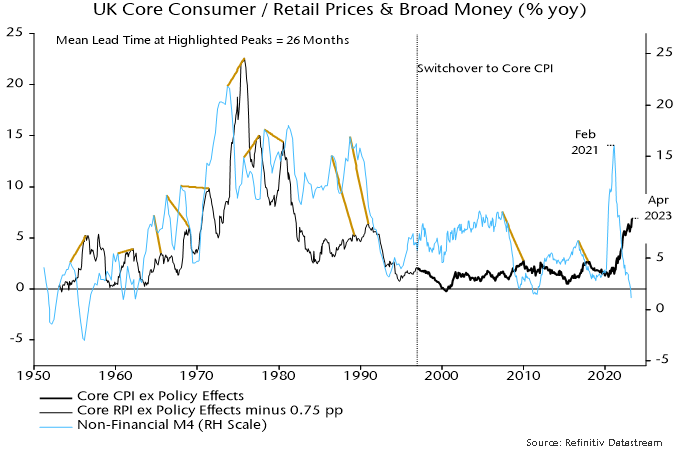

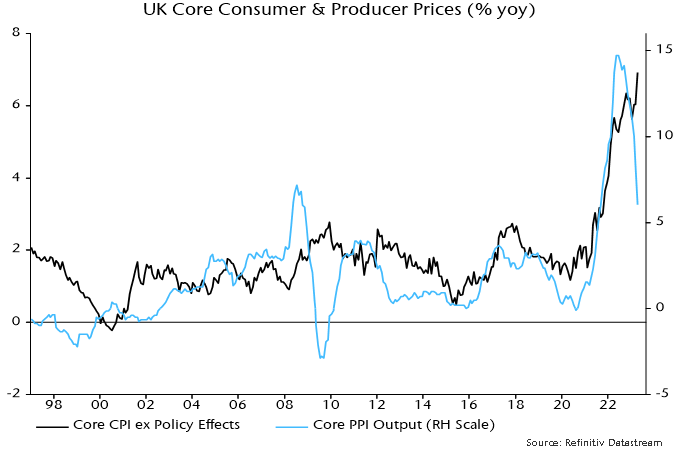

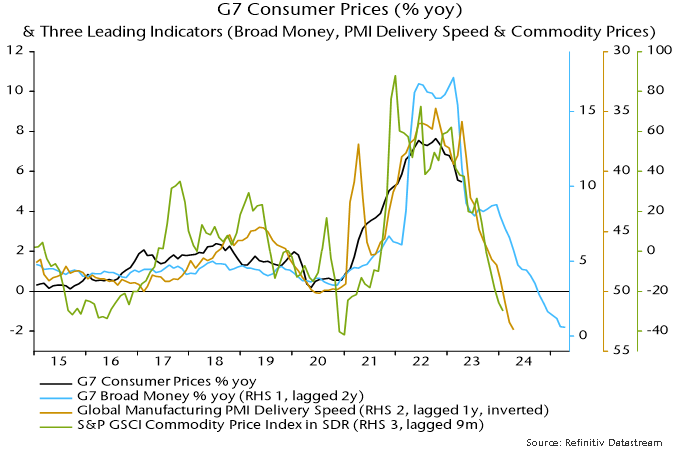

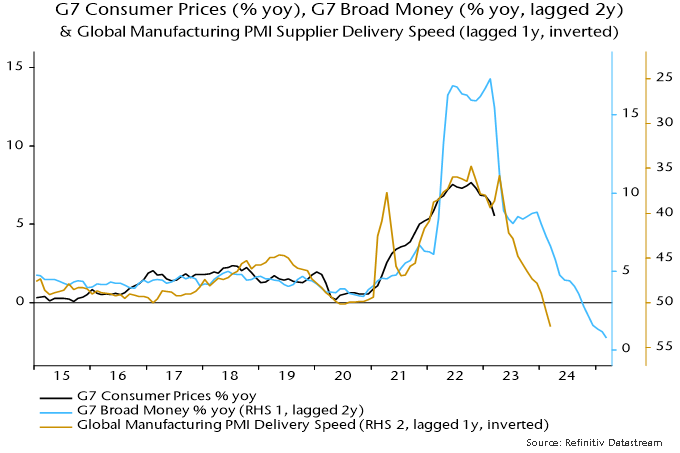

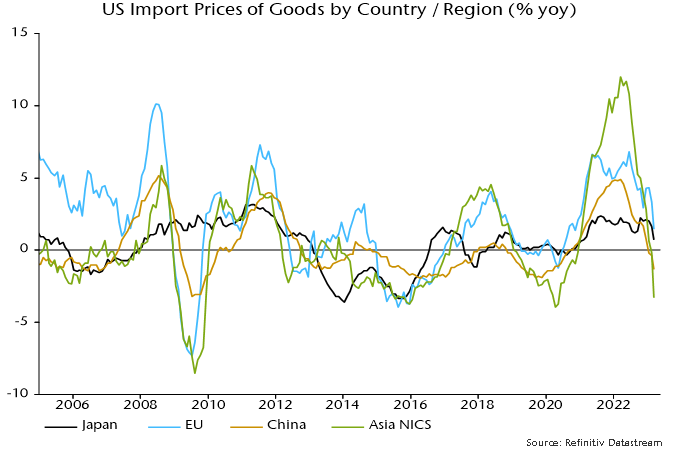

As in the UK, six-month headline inflation is tracking a simplistic “monetarist” forecast based on the profile of broad money momentum two years earlier – see chart 1. This relationship suggests that six-month CPI momentum will be back at about 2% in spring 2024, with the annual rate following during H2.

Chart 1

The projected return to 2% next spring is a reflection of a fall in six-month broad money momentum below 5% annualised in spring 2022. A subsequent decline in money momentum to zero suggests an inflation undershoot or even falling prices in 2025.

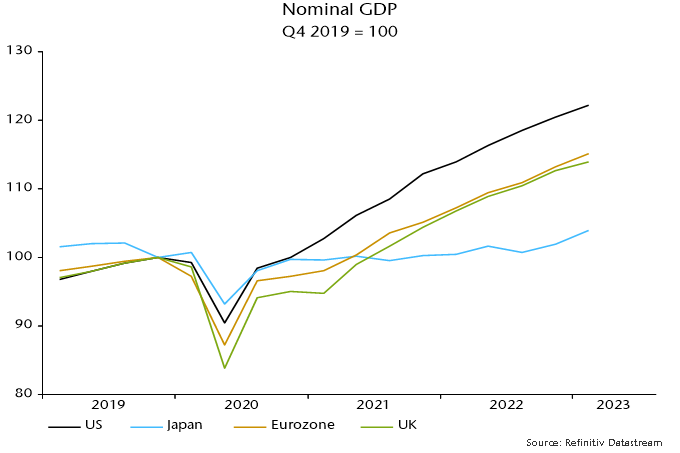

The shocking implication is that monetary trends were already consistent with a return of inflation to target before the ECB started hiking rates in July 2022. The 425 bp rise since then represents grotesque overkill, confirmed by recent monetary stagnation / contraction.

The corollary is that a huge and embarrassing policy reversal is likely to be necessary over the next 12-24 months, unless some other factor causes broad money momentum to recover to a target-consistent pace.

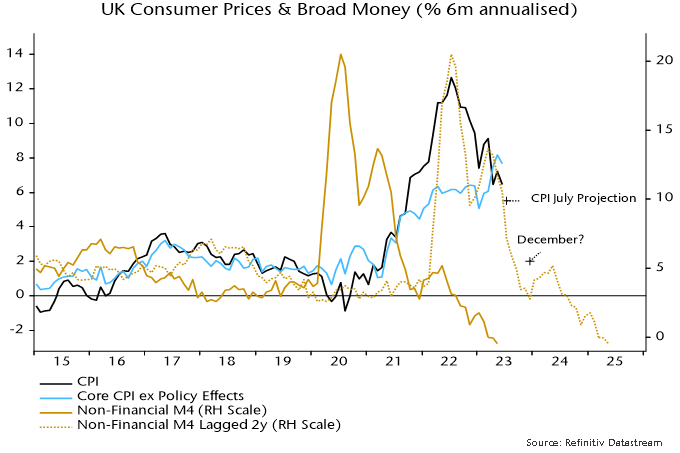

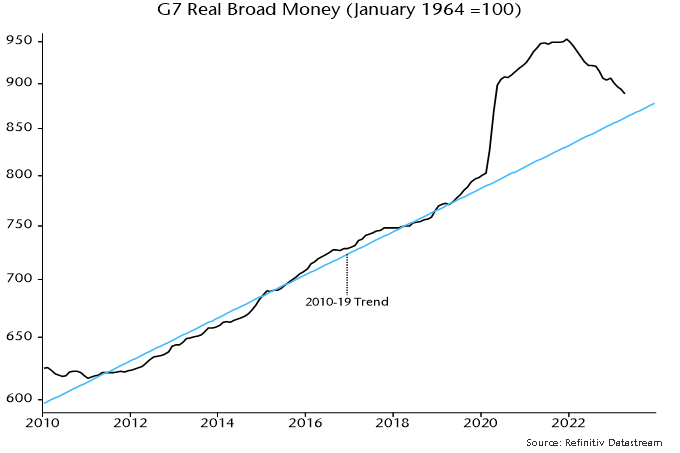

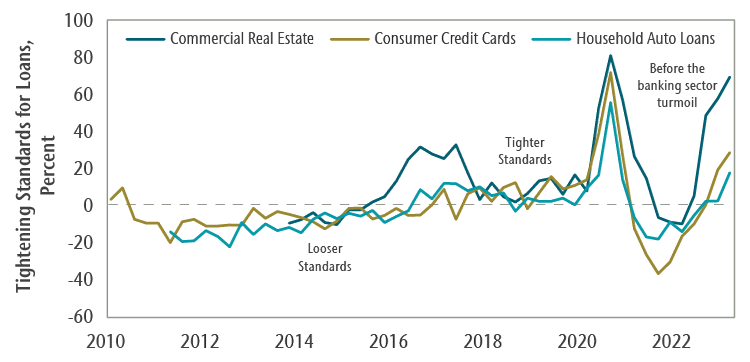

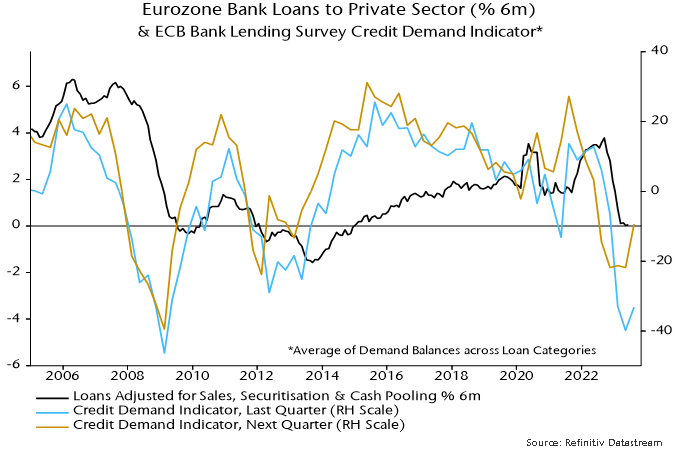

That seems a remote possibility, based on consideration of the “credit counterparts”. Loan demand balances in the latest ECB bank lending survey were less negative but still suggestive of negligible private credit expansion – chart 2.

Chart 2

Credit to government may contract given QT, withdrawal of TLTRO funding and inverted yield curves. (Banks previously used cheap TLTRO finance to buy higher-yielding government securities.) Redemptions of public sector debt held under the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme amount to €262 billion over the next 12 months, equivalent to 1.6% of M3.

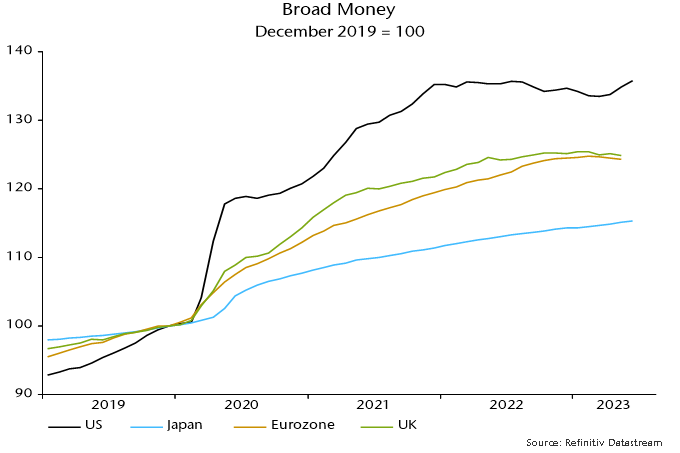

Broad money momentum has been supported recently by an increase in banks’ net external assets, reflecting a strengthening basic balance of payments (current account plus non-bank capital flows) – chart 3. This could accelerate as a Eurozone recession swells the current account surplus but is unlikely to outweigh domestic credit weakness.

Chart 3