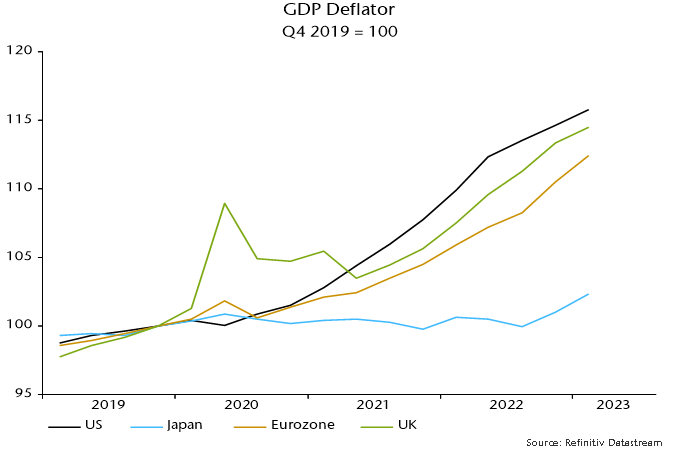

The money and cycles forecasting approach suggested that global inflation would fall rapidly during 2023 but at the expense of significant economic weakness. The inflation forecast played out but activity proved more resilient than expected. What are the implications for the coming year?

One school of thought is that economic resilience will limit further inflation progress, resulting in central banks disappointing end-2023 market expectations for rate cuts, with negative implications for growth prospects for late 2024 / 2025.

A second scenario, favoured here, is that the economic impact of monetary tightening has been delayed rather than avoided, and a further inflation fall during H1 2024 will be accompanied by significant activity and labour market weakness, with corresponding underperformance of cyclical assets.

The dominant market view, by contrast, is that further inflation progress will allow central banks to ease pre-emptively and sufficiently to avoid material near-term weakness and lay the foundation for economic acceleration into 2025.

On the analysis here, the second scenario might warrant a two-thirds probability weighting versus one-sixth for the first and third. This assessment reflects several considerations.

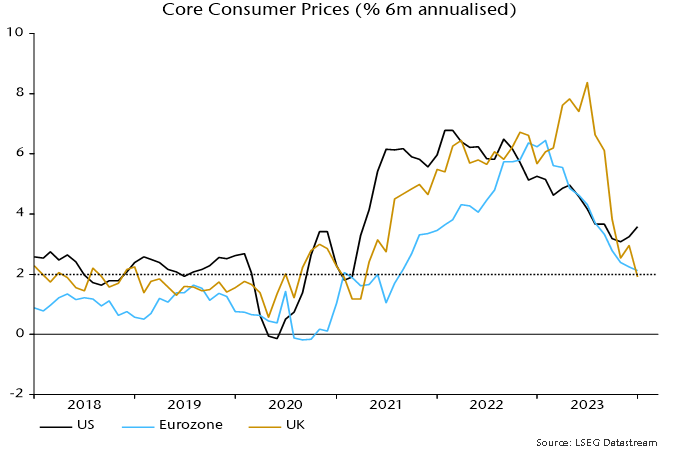

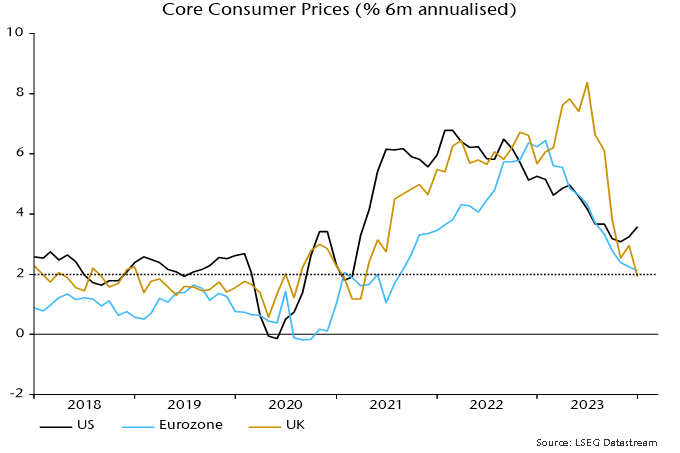

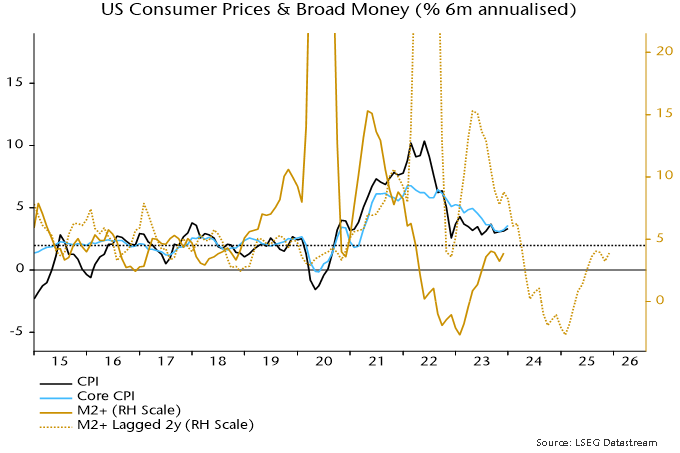

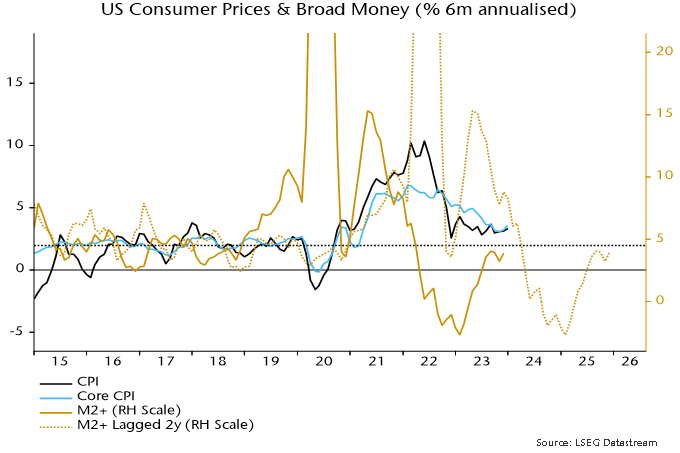

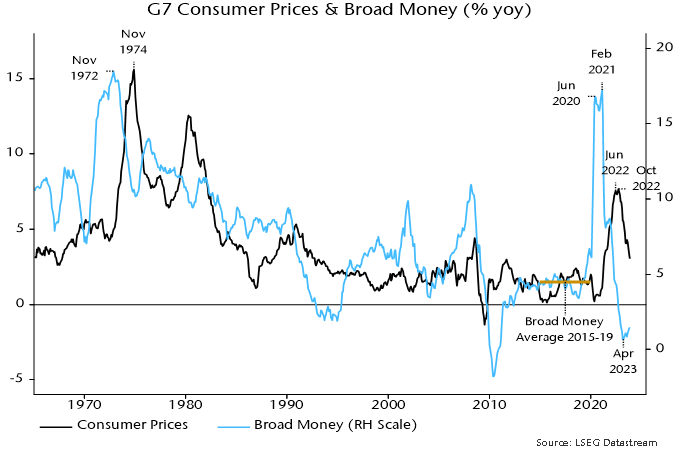

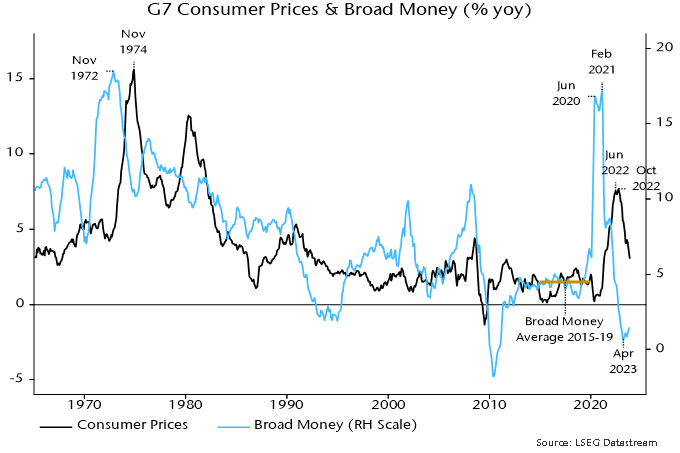

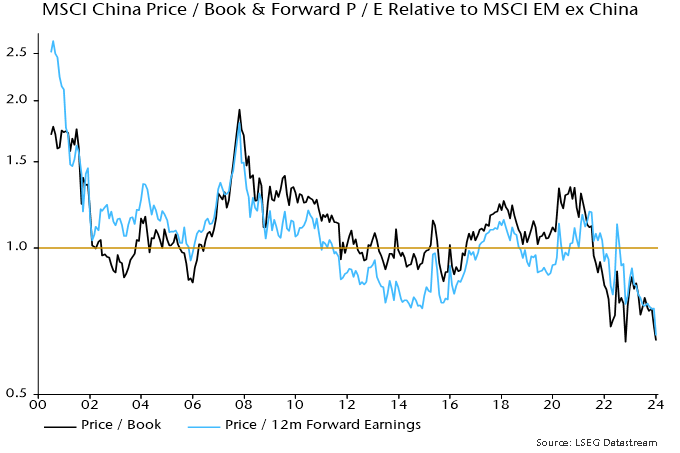

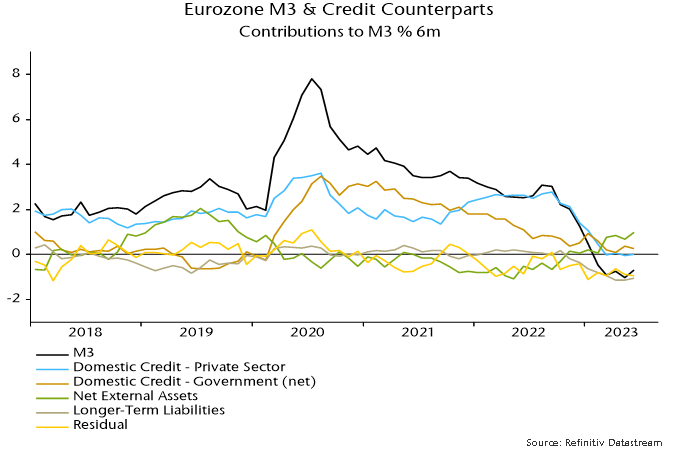

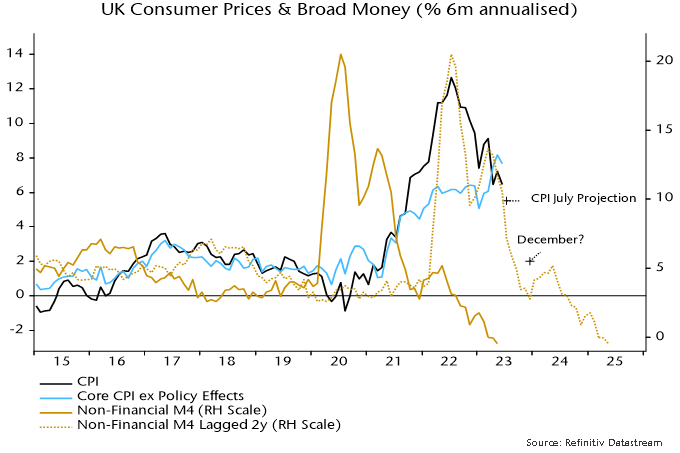

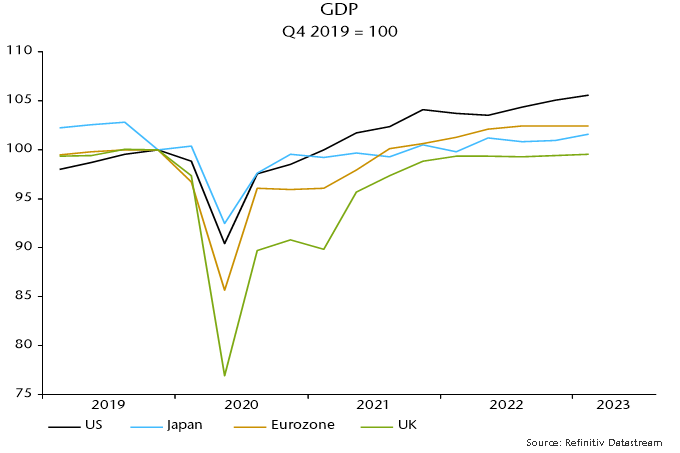

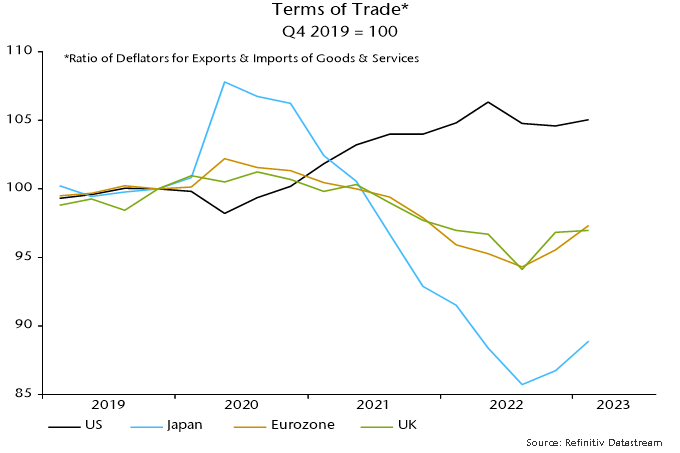

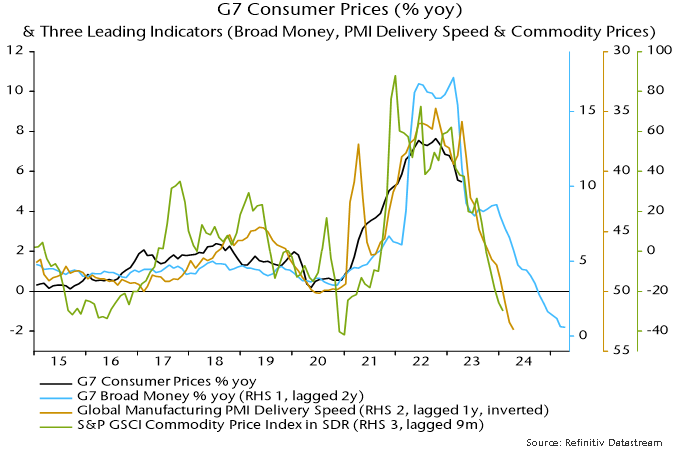

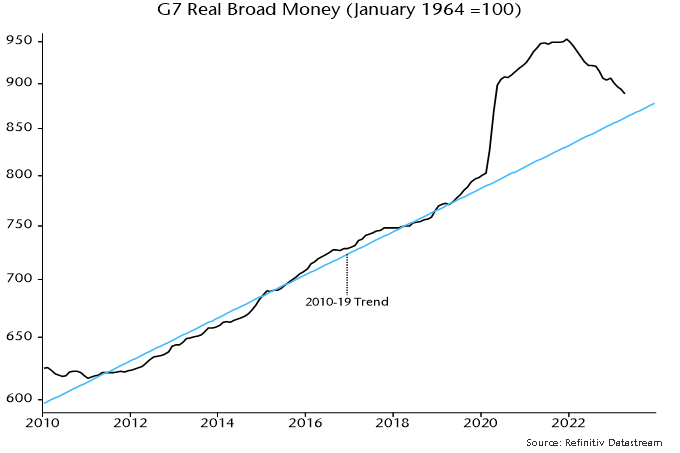

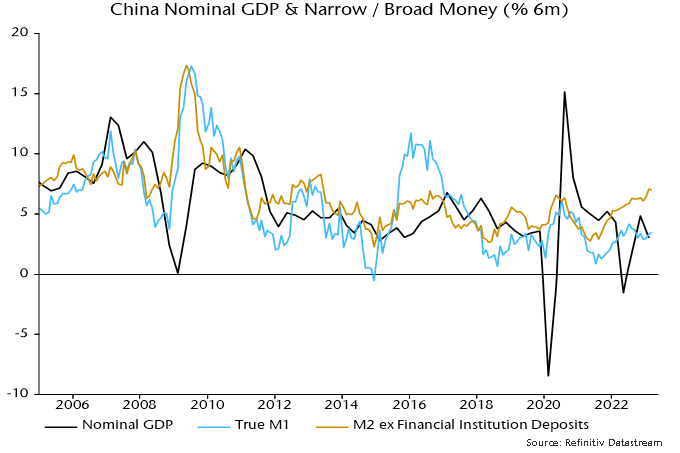

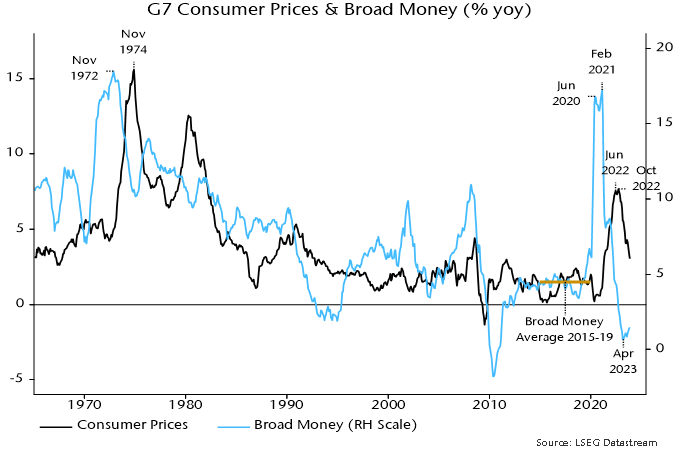

First, on inflation, developments continue to play out in line with the simplistic “monetarist” proposition of a two-year lead from money to prices. G7 annual broad money growth formed a double top between June 2020 and February 2021 – mid-point October 2020 – and declined rapidly thereafter. Annual CPI inflation peaked in October 2022, falling by 60% by November 2023 – chart 1.

Chart 1

Broad money growth returned to its pre-pandemic average in mid-2022 and continued to decline into early 2023. The suggestion is that inflation rates will return to targets by H2 2024 with a subsequent undershoot and no sustained revival before mid-2025.

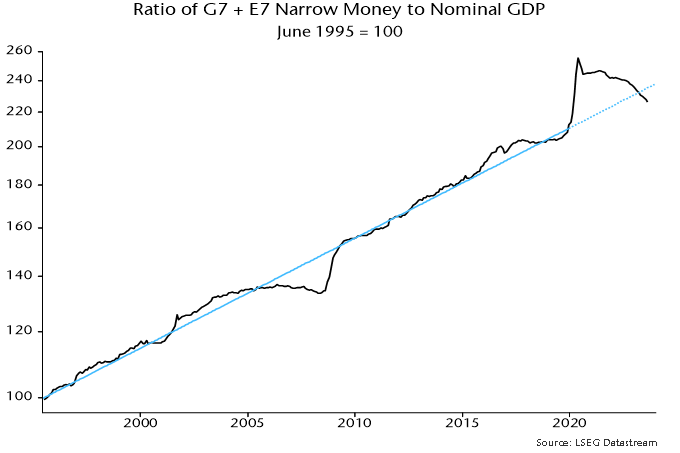

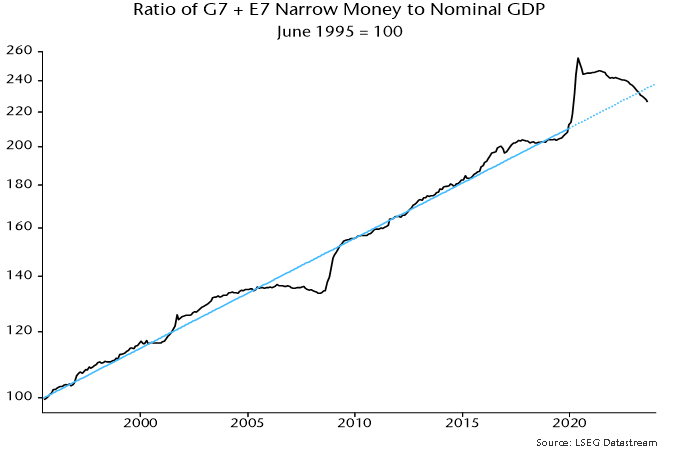

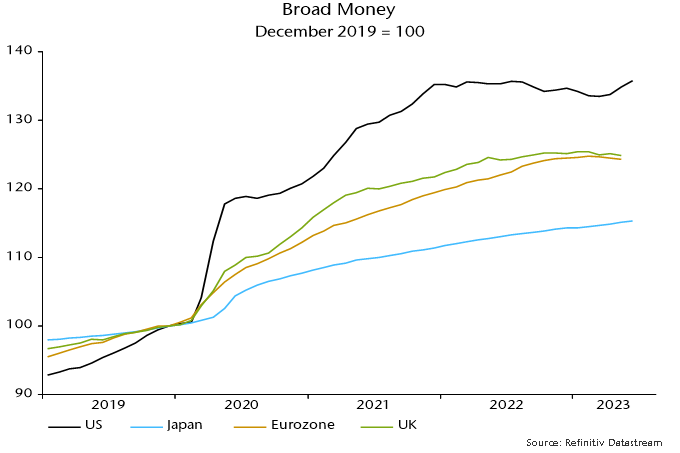

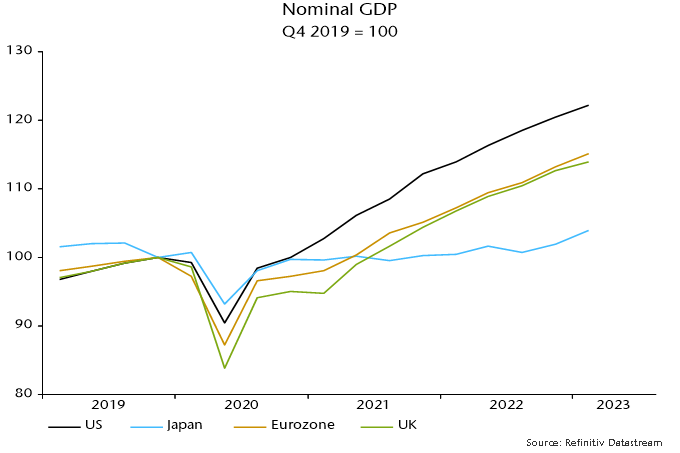

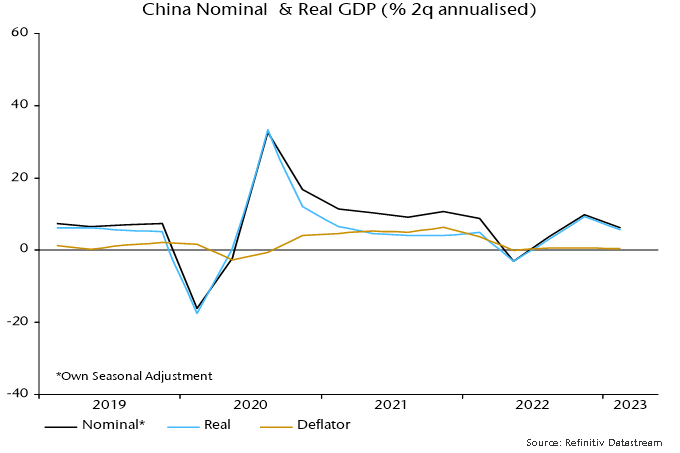

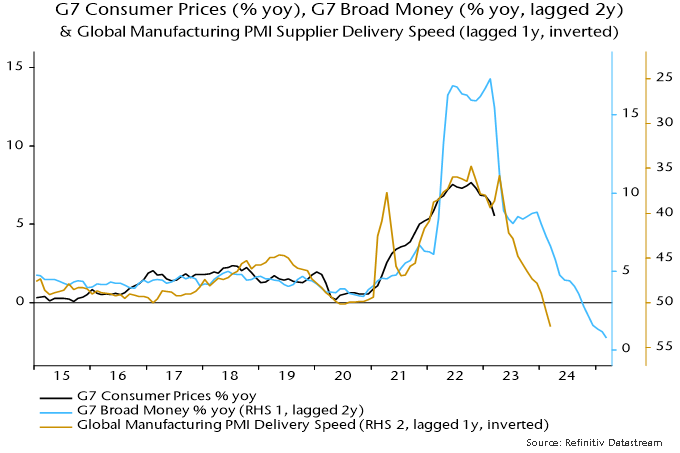

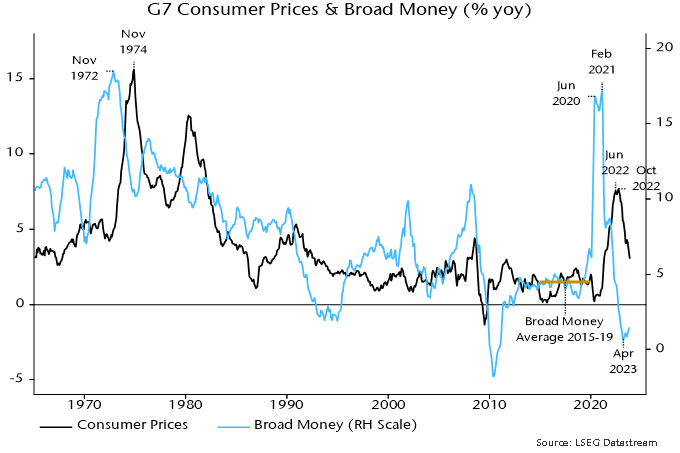

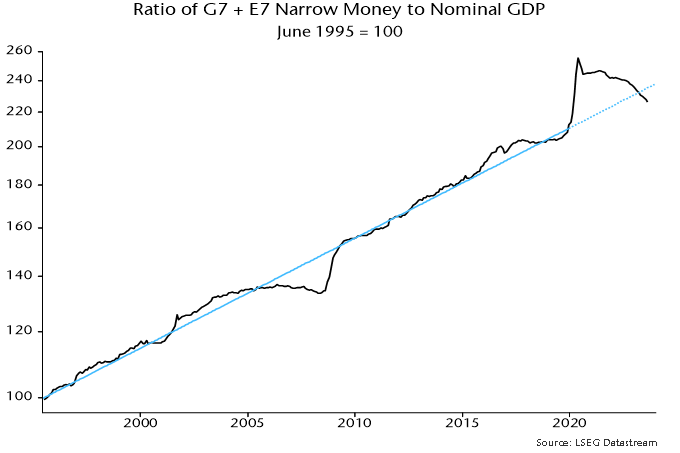

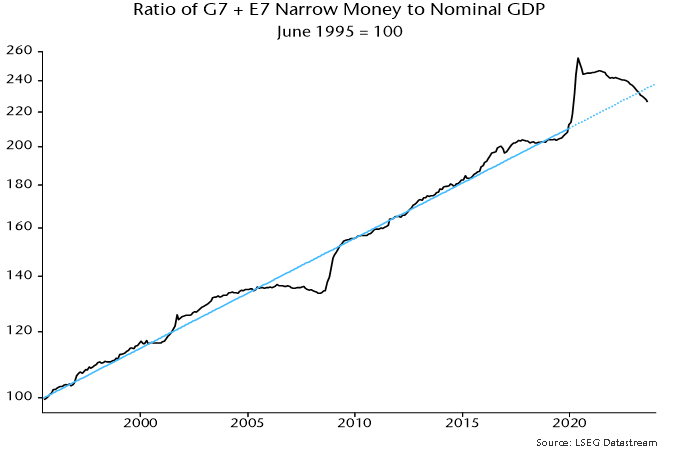

Secondly, economic resilience in 2023 partly reflected post-pandemic demand / supply catch-up effects. On the demand side, an analytical mistake here was to downplay the supportive potential of an overhang of “excess” money balances following the 2020-21 monetary explosion. Globally, this excess stock has probably now been eliminated – chart 2.

Chart 2

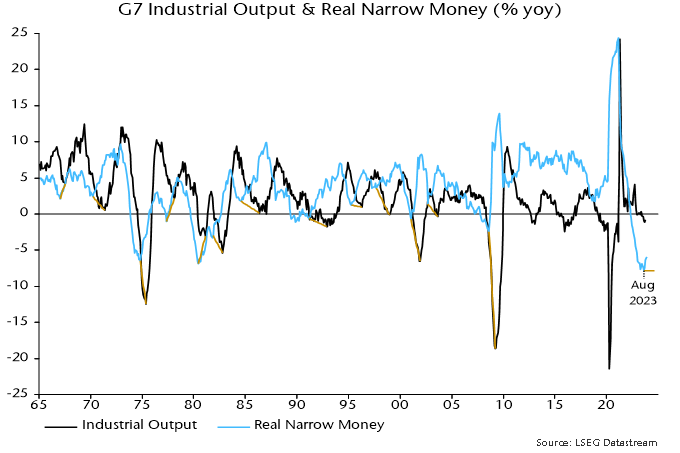

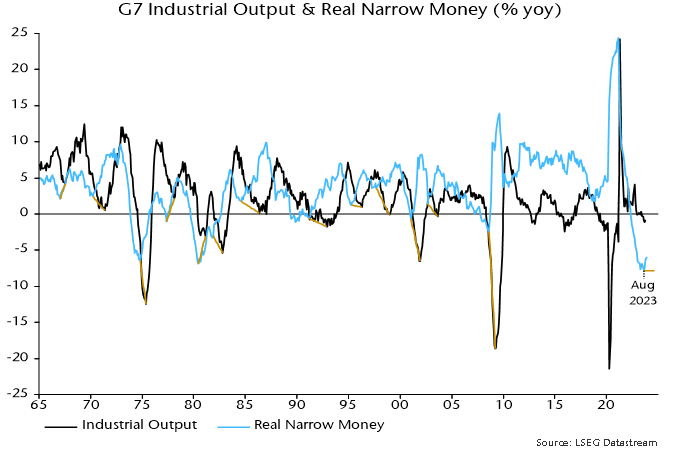

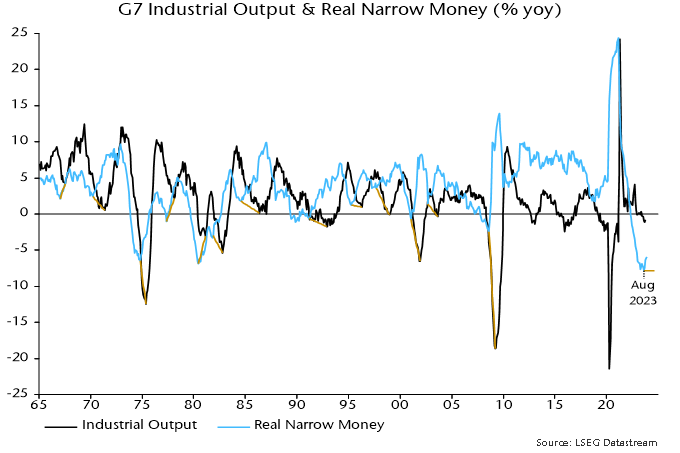

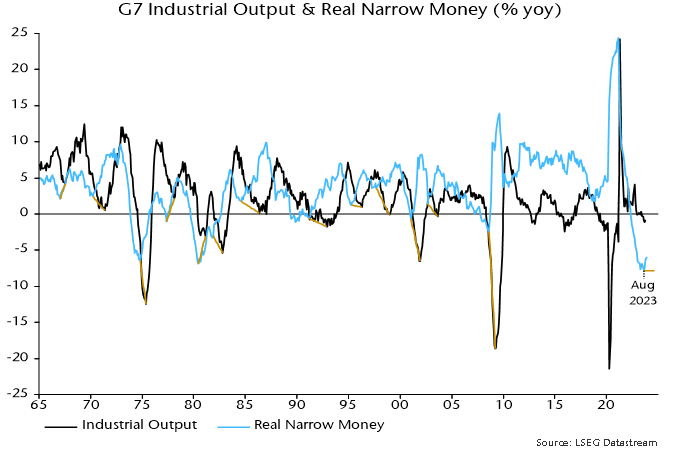

The moderate economic impact of monetary tightening to date, moreover, is consistent with historical experience. Major lows in G7 annual real narrow money momentum led lows in industrial output momentum by an average 12 months historically – chart 3. With a trough in the former reached as recently as August 2023, economic fall-out may not be fully apparent until H2 2024.

Chart 3

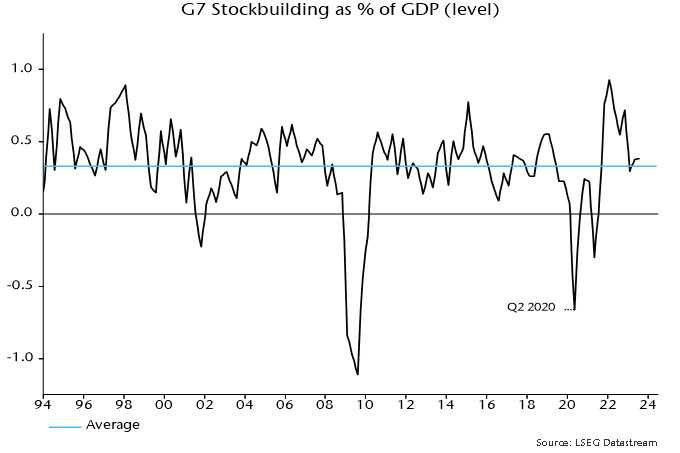

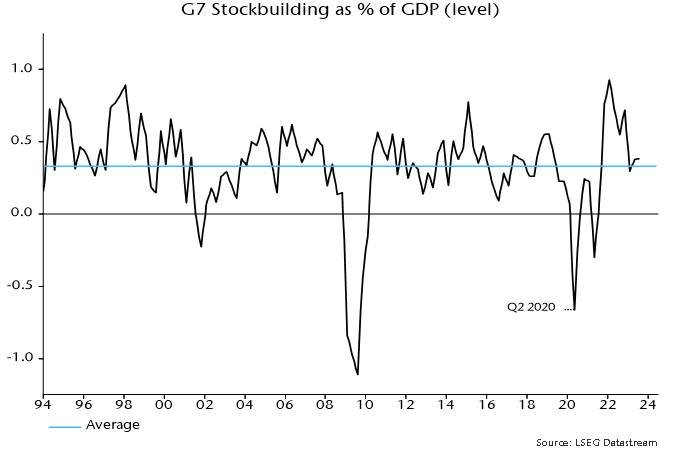

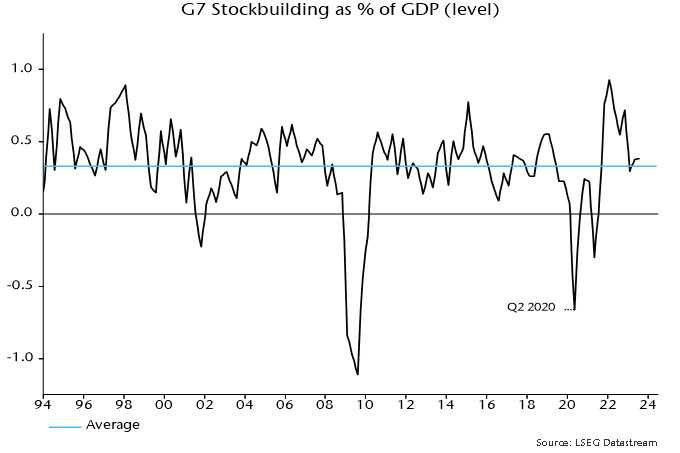

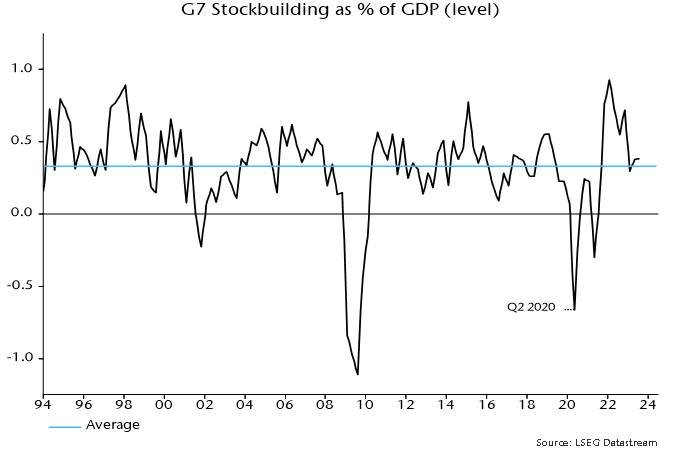

The suggestion that economic downside is incomplete is supported by a revised assessment of cyclical influences. The previous hypothesis here was that the global stockbuilding cycle would bottom out in late 2023 and recover during 2024. Recent stockbuilding data, however, appear to signal that the cycle has extended, with a recovery pushed back until H2 2024.

The assumption of a late 2023 trough was based on a previous low in Q2 2020 and the average historical cycle length of 3 1/3 years. This seemed on track at mid-2023: G7 stockbuilding had crossed below its long-run average in Q1, consistent with a trough-compatible level being reached in H2 – chart 4. The downswing, however, was interrupted in Q2 / Q3, with a further decline likely to be necessary to complete the cycle and form the basis for a recovery.

Chart 4

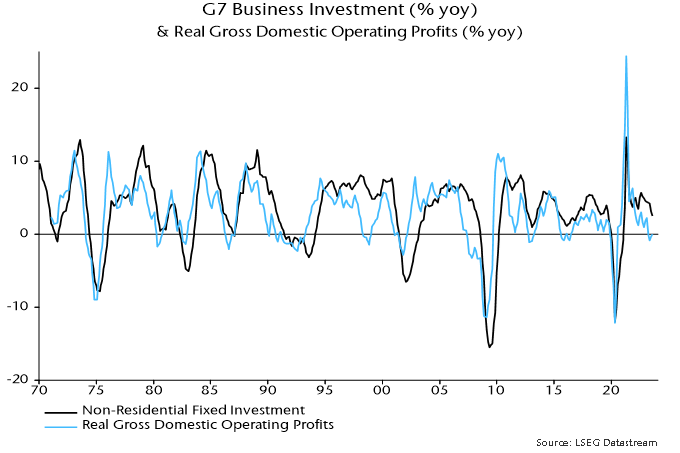

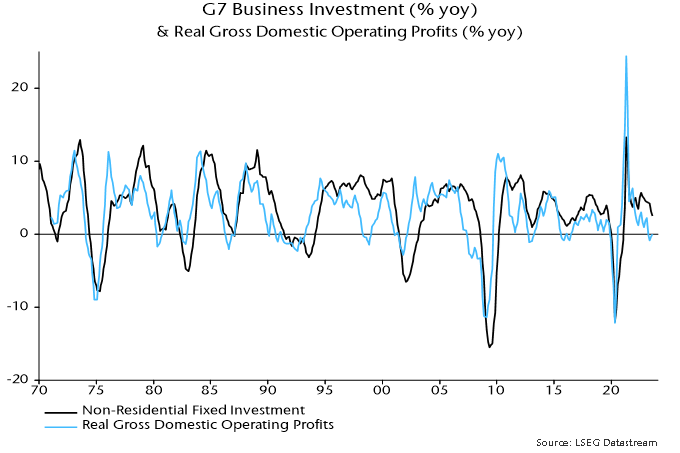

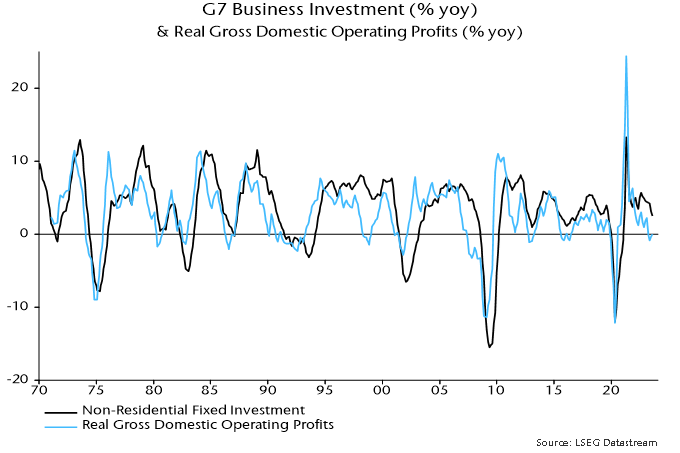

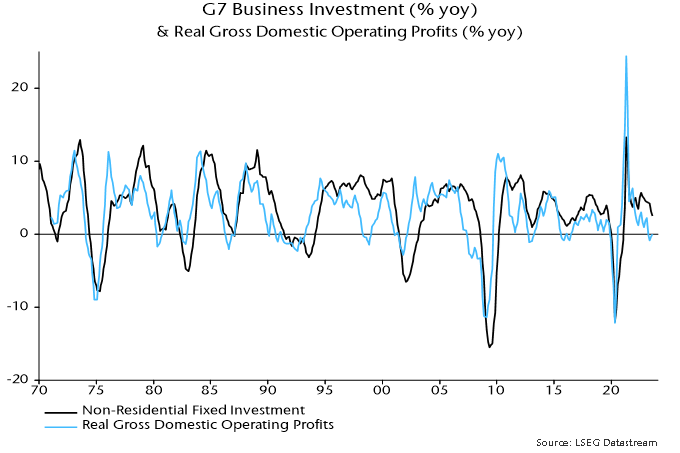

A resumed drag from stockbuilding may be accompanied by a further slowdown or outright weakness in business investment, reflecting recent stagnation in real profits – chart 5. Capex is closely correlated with hiring decisions, so this also argues for a faster loosening of labour market conditions.

Chart 5

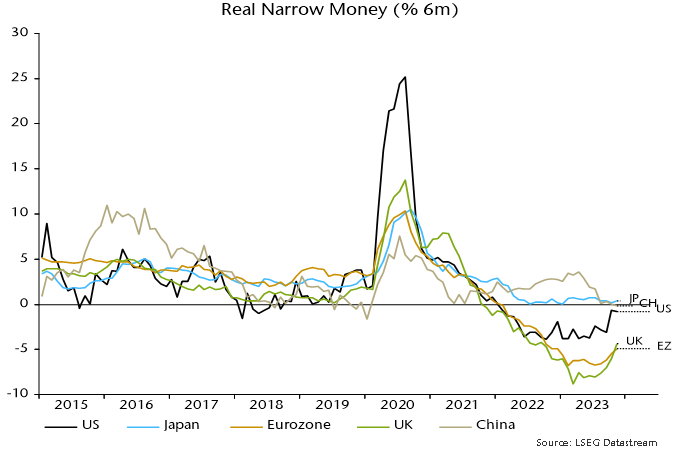

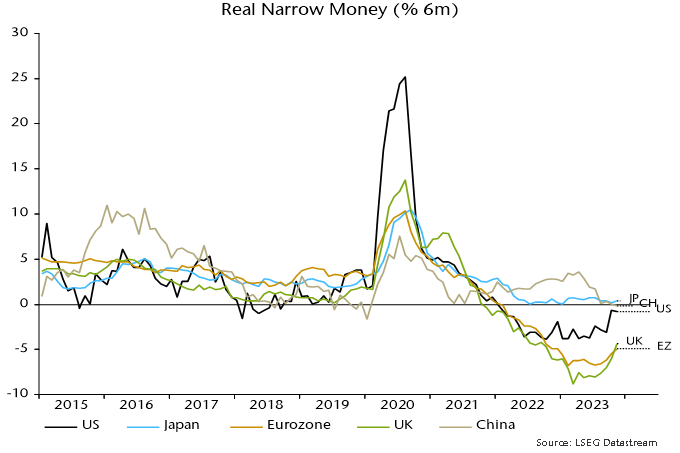

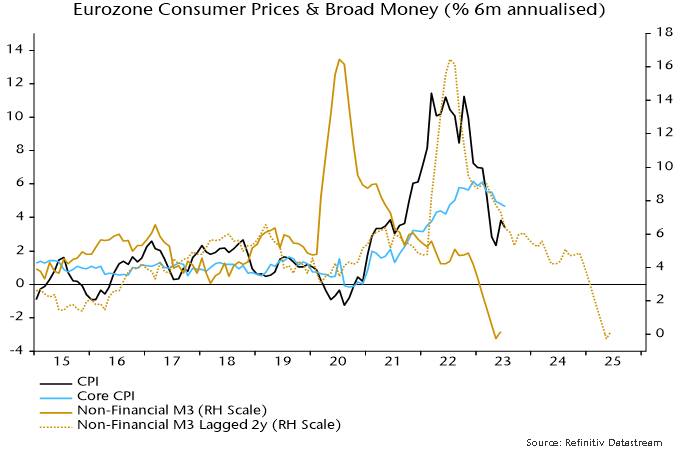

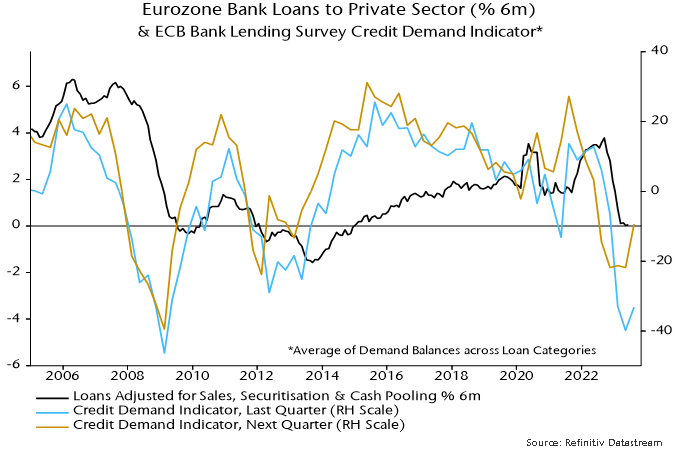

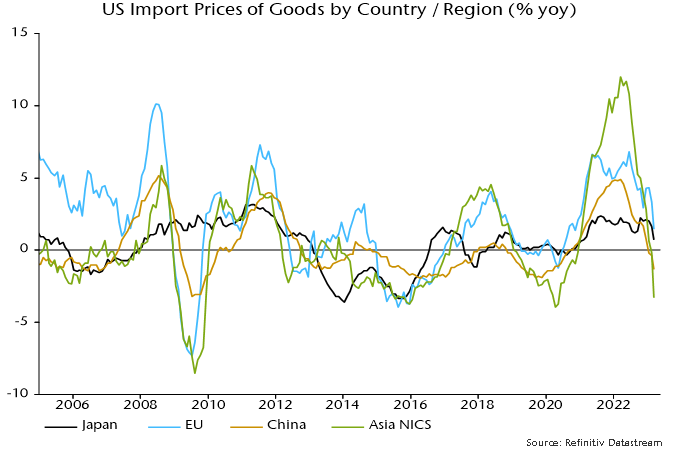

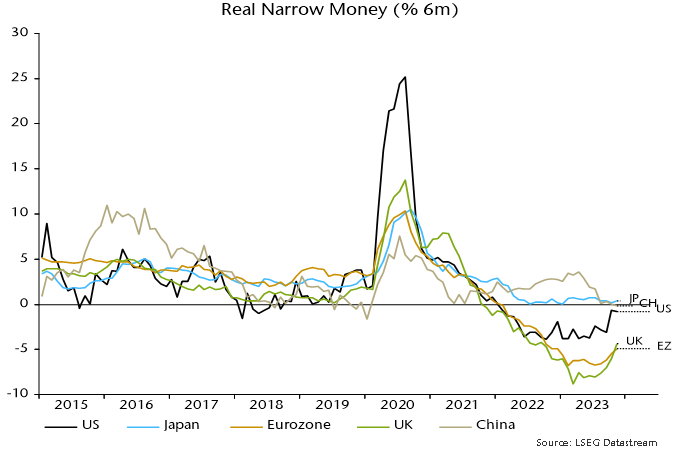

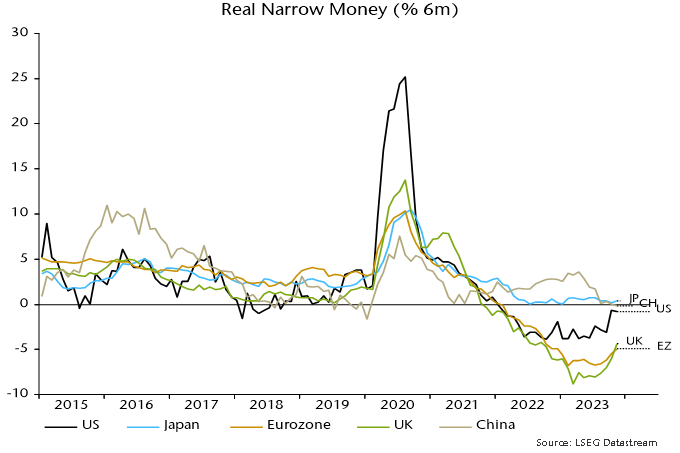

Real narrow money momentum remains weaker in Europe than the US, suggesting continued economic underperformance and a more urgent need for policy relaxation – chart 6. Six-month rates of change are off the lows but need to rise significantly to warrant H2 recovery hopes. Globally, the US / European revivals have been partly offset by a further slowdown in China, suggesting still-weakening economic prospects.

Chart 6

The frenetic rally of the final two months resulted in global equities delivering a strong return during 2023 despite the two “excess” money indicators tracked here* remaining negative throughout the year. The indicators, however, started flashing red around end-2021, since when the MSCI World index has slightly underperformed US dollar cash.

Historically (i.e. since 1970), equities outperformed cash on average only when both indicators were positive, a condition unlikely to be met until mid-2024 at the earliest.

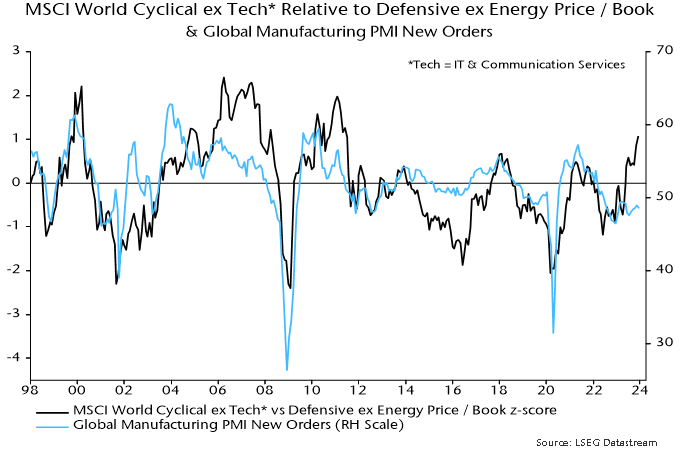

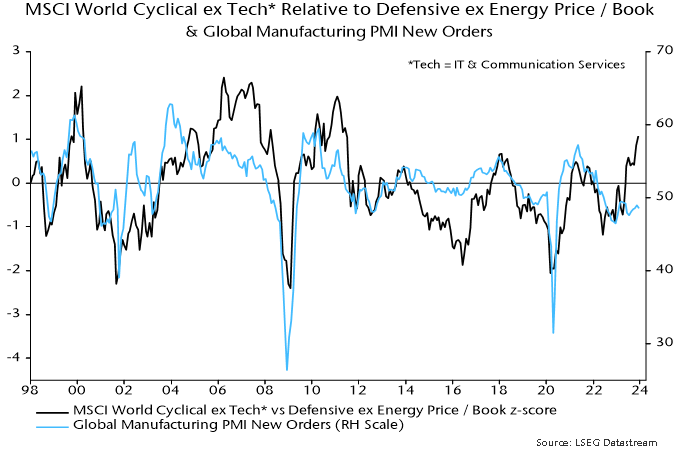

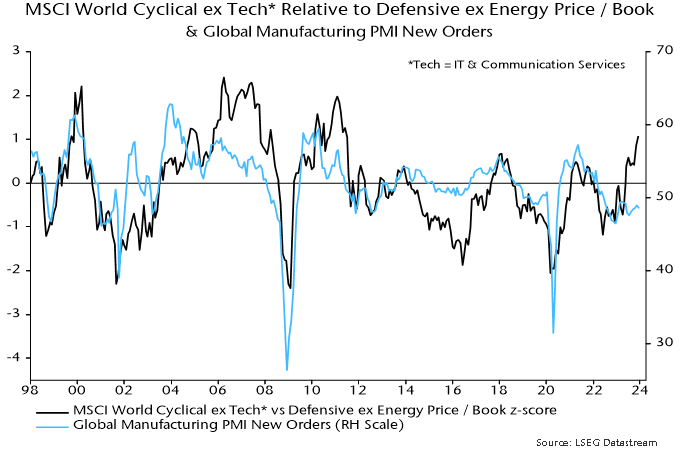

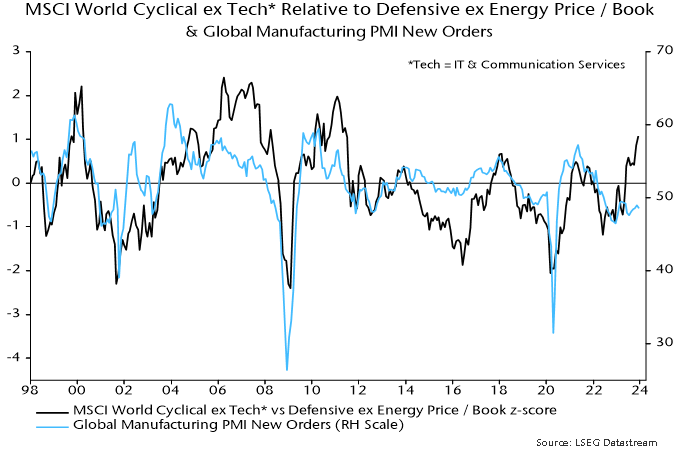

The late 2023 rally was led by cyclical sectors as investors embraced a “soft landing” scenario. Non-tech cyclical sectors ended the year more than one standard deviation expensive relative to history versus defensive ex. energy sectors on a price / book basis – chart 7. Current prices appear to discount an early / strong PMI recovery, which the earlier discussion suggests is unlikely.

Chart 7

Quality stocks outperformed during 2023, reversing a relative loss in 2022 and consistent with the historical tendency when “excess” money readings were negative. Earlier underperformance partly reflected an inverse correlation with Treasury yields, a relationship now suggesting further catch-up potential.

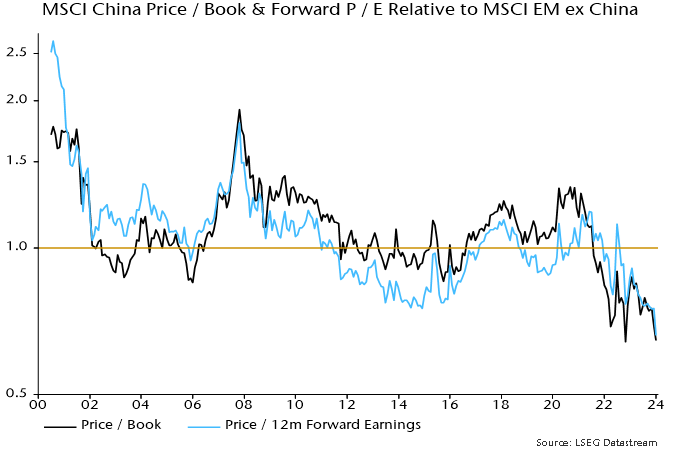

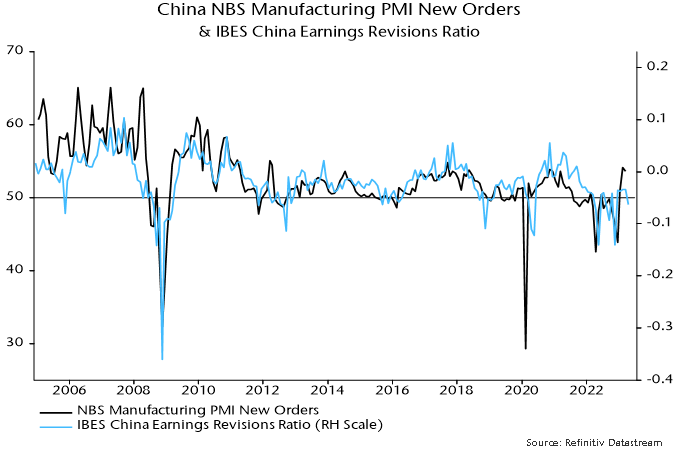

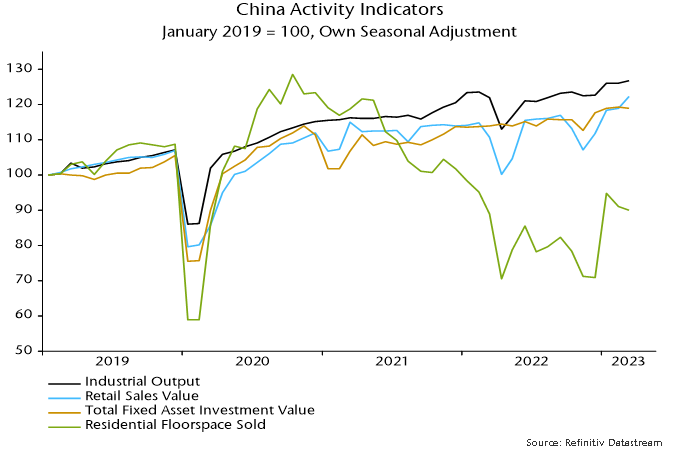

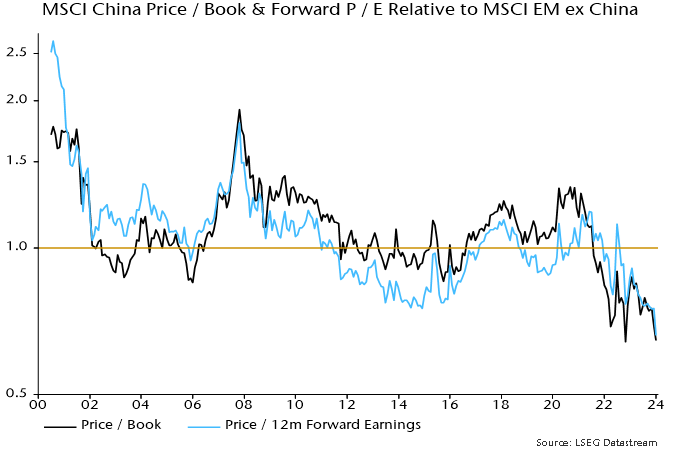

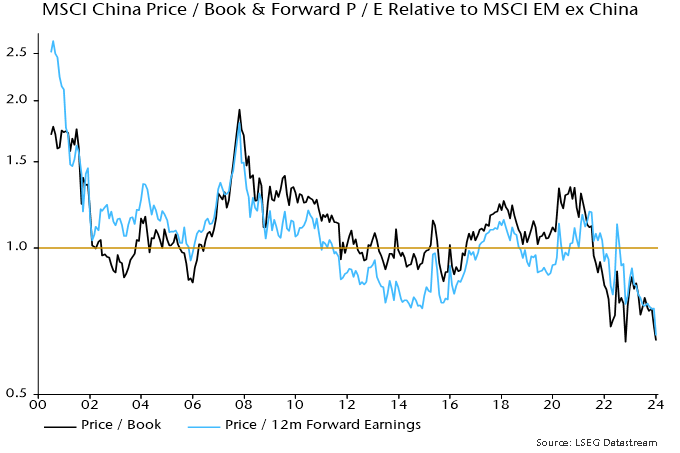

Contributing factors to the dramatic underperformance of Chinese stocks during 2023 include excessively optimistic post-reopening economic expectations at end-2022 and unexpectedly restrictive monetary / fiscal policies. MSCI China is at a record** valuation discount to the rest of EM – chart 8 – while monetary / economic weakness suggests an early policy pivot.

Chart 8

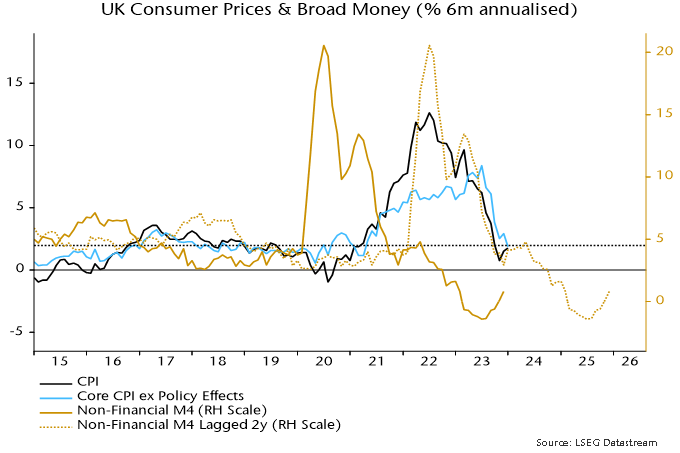

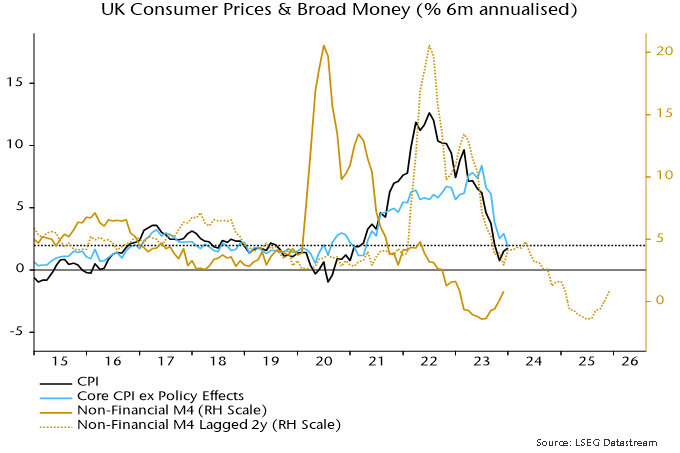

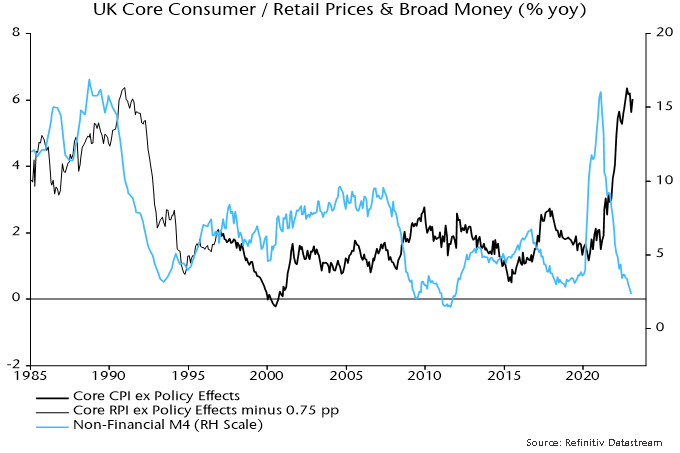

A key issue for 2024 is the extent to which central bank policy easing will revive money growth. While inflation is expected to trend lower into early 2025, the cycles framework suggests another upswing later this decade – the 54-year Kondratyev price / inflation cycle last peaked in 1974. Aggressive Fed easing 54 years ago – in 1970 – pushed annual broad money growth into double-digits the following year, creating the conditions for the final Kondratyev ascent. Signs that a similar scenario is playing out would warrant adding to inflation hedges.

*The differential between G7 plus E7 six-month real narrow money and industrial output momentum and the deviation of 12-month real narrow money momentum from a long-term moving average.

**Since June 2000. MSCI China included only B-shares through May 2000, when red chips and H-shares were added.