Chinese money and credit numbers for December suggest that policy stimulus is becoming effective, warranting an upgraded assessment of economic prospects.

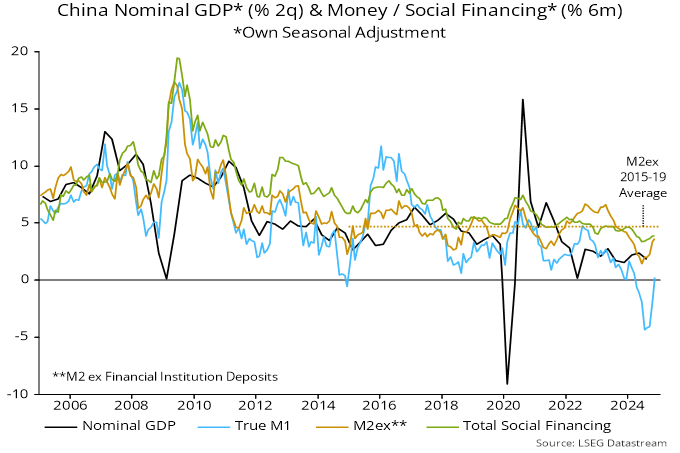

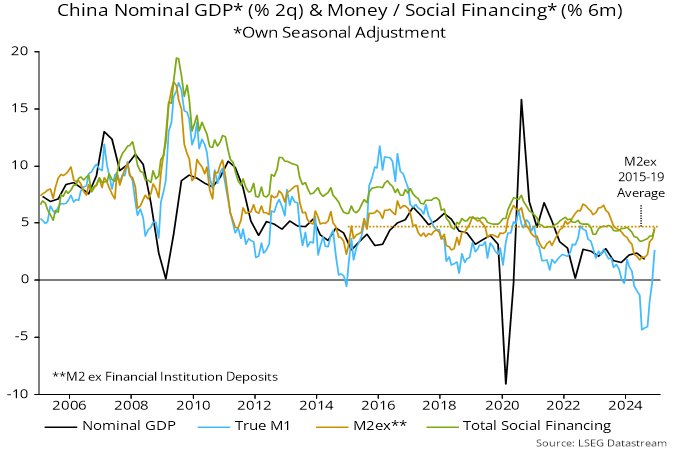

Six-month rates of change of broad / narrow money and broad credit (total social financing) bottomed in June / July but the recovery through November was modest. All three jumped higher in December – see chart 1.

Chart 1

Money measures – particularly narrow money – were negatively distorted last spring by regulatory enforcement of deposit rate ceilings*. The revival in six-month momentum partly reflects the dropping out of this effect. Still, December readings should be undistorted and broad money momentum is close to its 2015-19 average, when nominal GDP grew solidly.

Monetary financing of fiscal easing has been a key driver of the money growth pick-up. Banking system net lending to government (including by the PBoC) contributed 2.0 pp (not annualised) to M2 growth in the six months to December, the most since the 2015-16 stimulus episode.

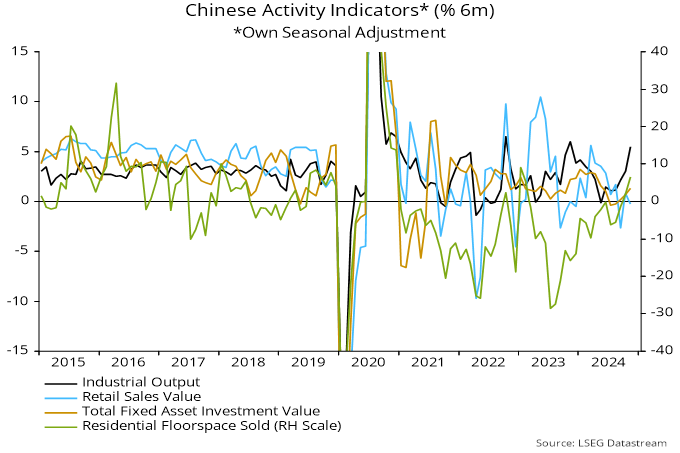

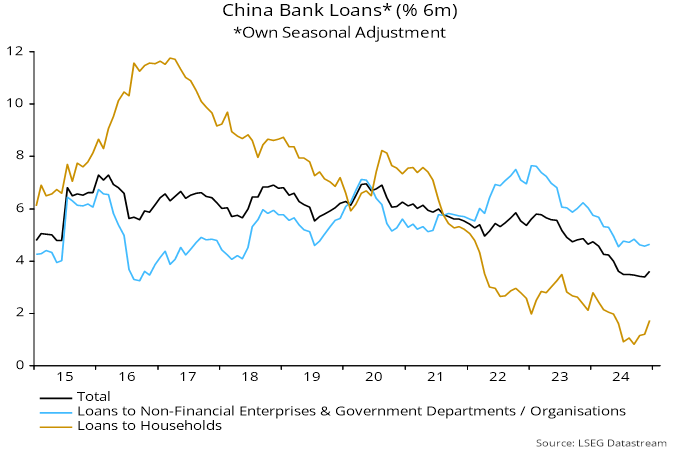

An apparent weak spot in the December release was a further fall in annual bank loan growth (i.e. excluding lending to government). The numbers, however, are being distorted by debt swap operations, involving repayment of bank loans by government-related organisations. Six-month loan momentum has edged up despite this drag, with household lending weakness abating – chart 2.

Chart 2

Will the money growth recovery continue? Recent renewed pressure on the currency has been associated with a resumption of f/x sales and a firming of money market rates. The increase in term rates has so far been modest and may be offset by ongoing support from money-financed fiscal easing.

*Lower interest rates on demand deposits resulted in enterprises moving money into time deposits and non-monetary instruments while repaying bank loans.