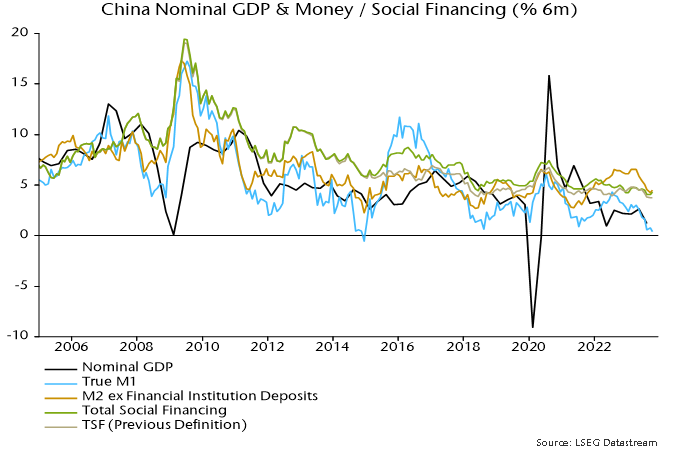

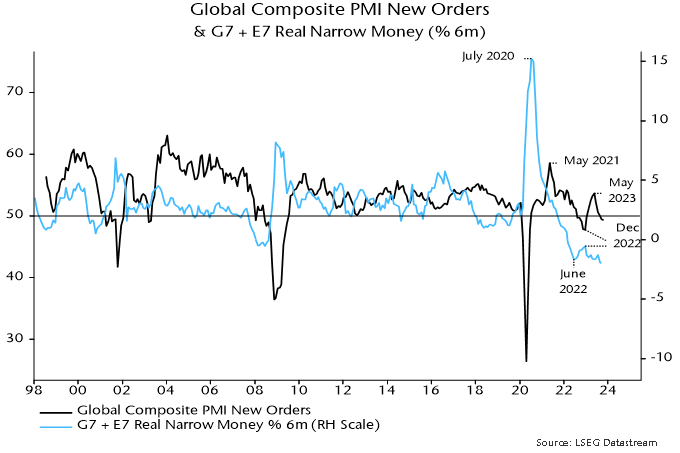

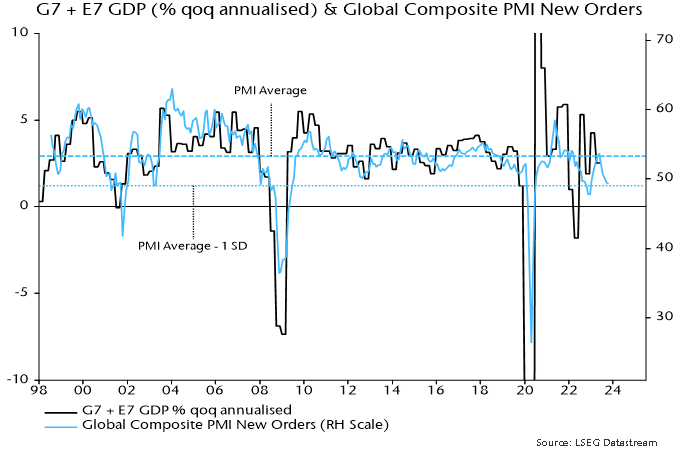

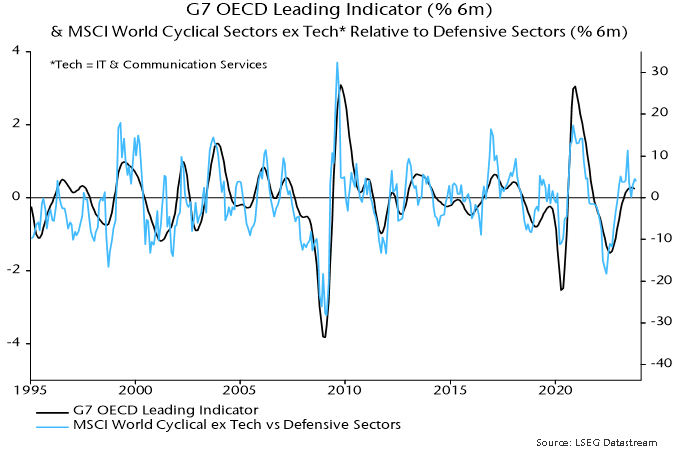

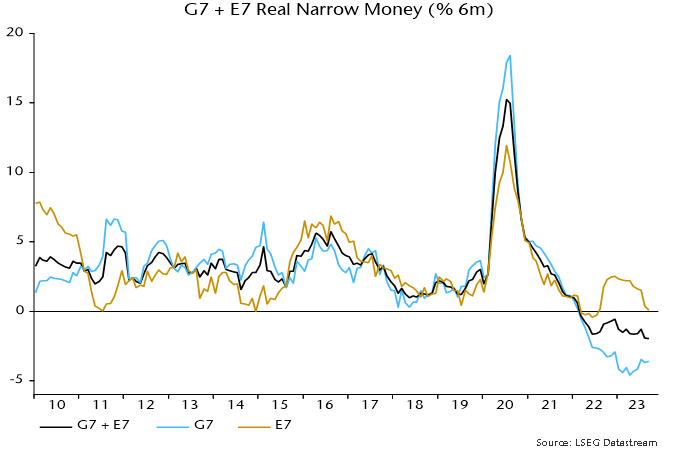

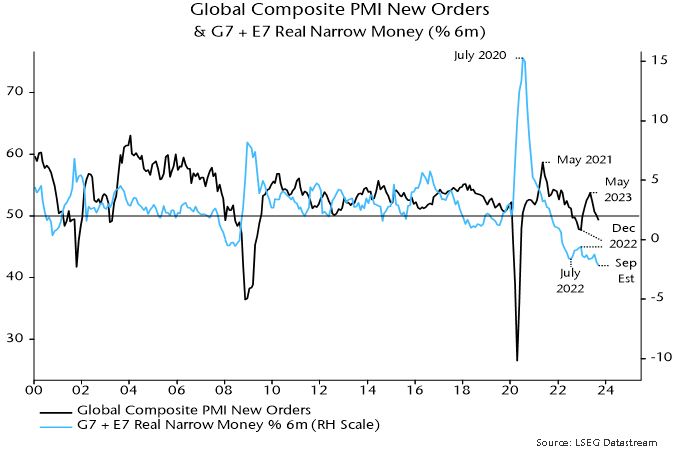

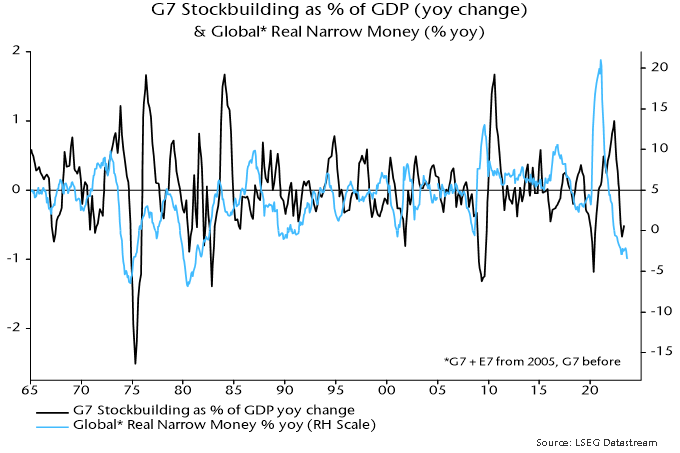

Global six-month real narrow money momentum – a key leading indicator in the forecasting approach employed here – is estimated to have rebounded in October, having reached a new low in September. Allowing for an average 6-7 month lead, this suggests that the global composite PMI new orders index will decline into end-Q1 2024 but may stabilise in Q2 if September is confirmed as a low for real money momentum – see chart 1.

Chart 1

One reason for thinking that September may have marked a low is that six-month consumer price momentum is likely to slow into Q1, based on current commodity prices.

In addition, six-month nominal narrow money momentum in the US, Eurozone and UK, while still very weak, appears to have bottomed, although a significant recovery is unlikely until central banks start easing.

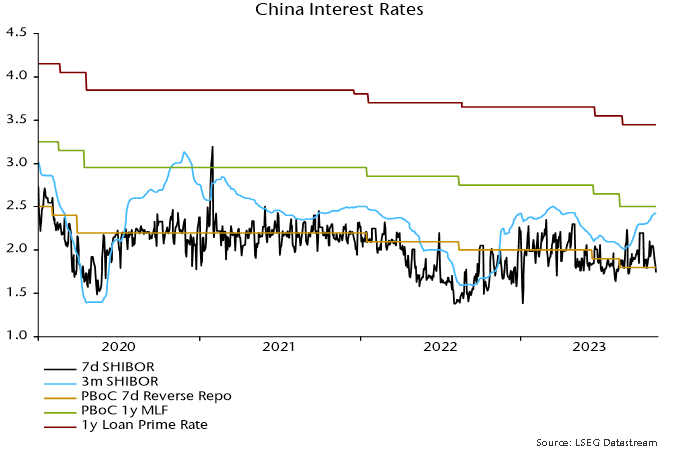

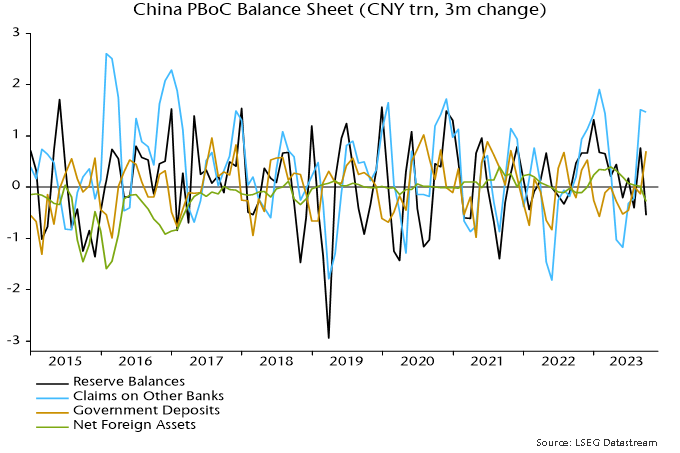

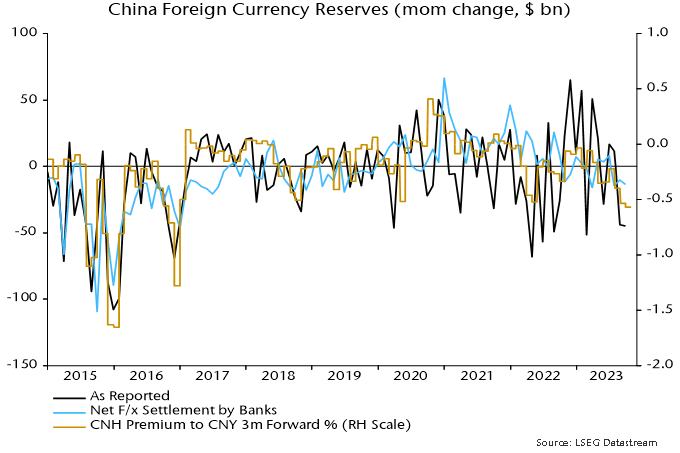

As previously discussed, the main driver of the further fall in global real money momentum into September was a sharp slowdown in China. A hope here that the PBoC would expand liquidity supply to lower elevated money market rates remains unfulfilled, suggesting that money trends will remain weak into early 2024. (The PBoC’s Q3 monetary policy report is worrying in this regard, apparently signalling a reduced emphasis on adjusting policy in response to strength or weakness in money and credit.)

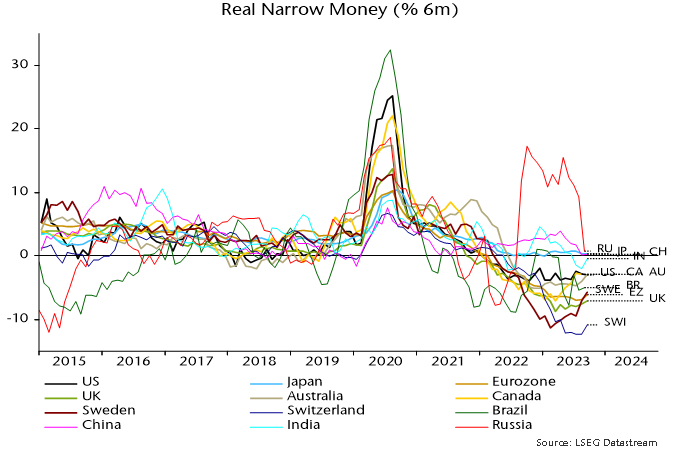

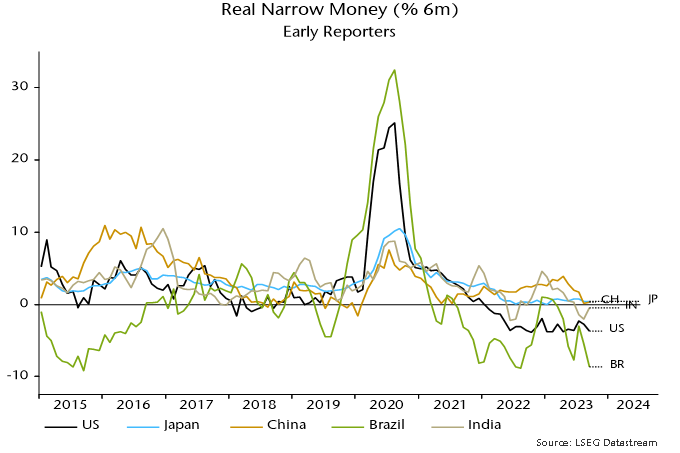

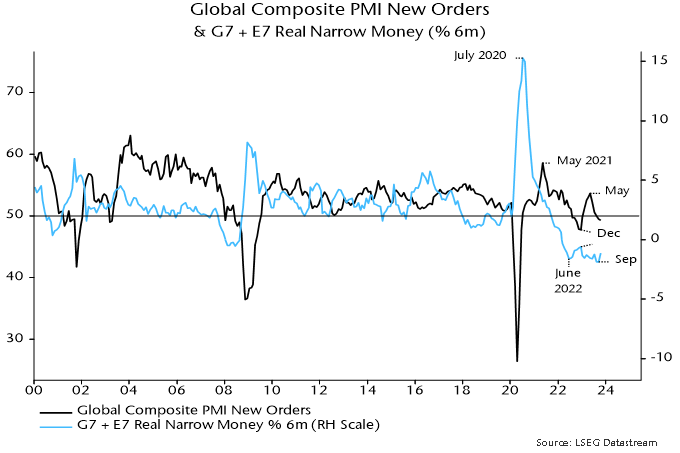

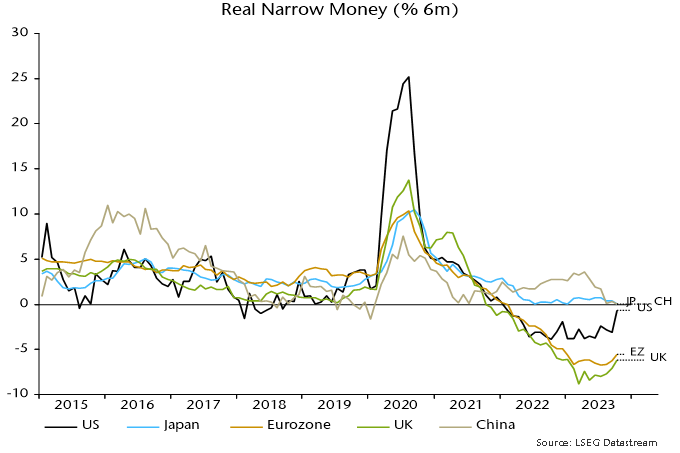

Among the major economies, six-month real narrow money momentum has recovered most in the US, although even here remains negative – chart 2.

Chart 2

This recovery suggests less bad US economic prospects for later in 2024 but should not be interpreted as implying a reduced probability of a near-term hard landing / recession.

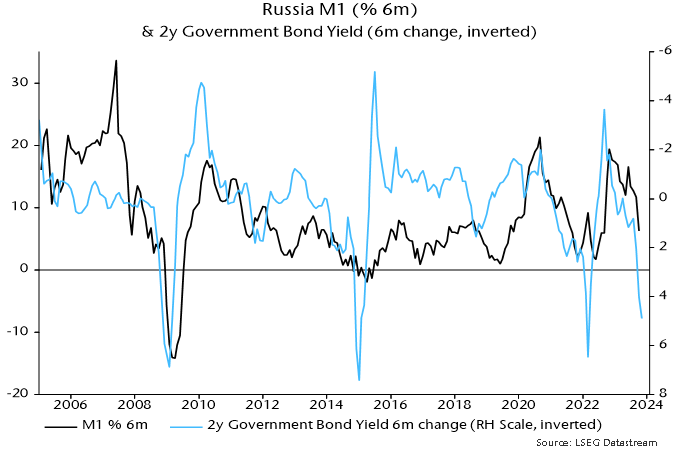

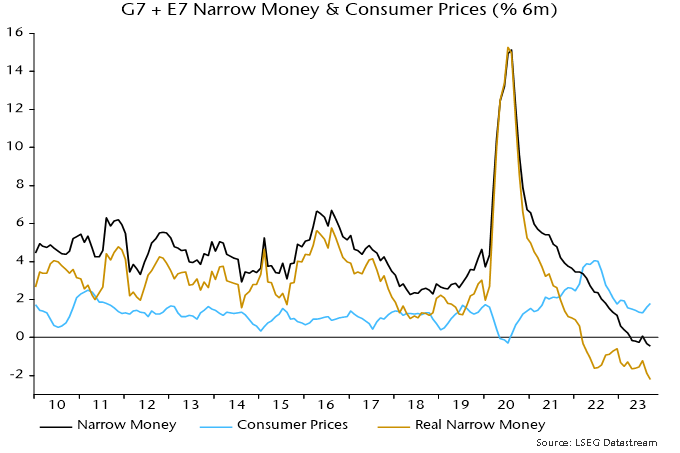

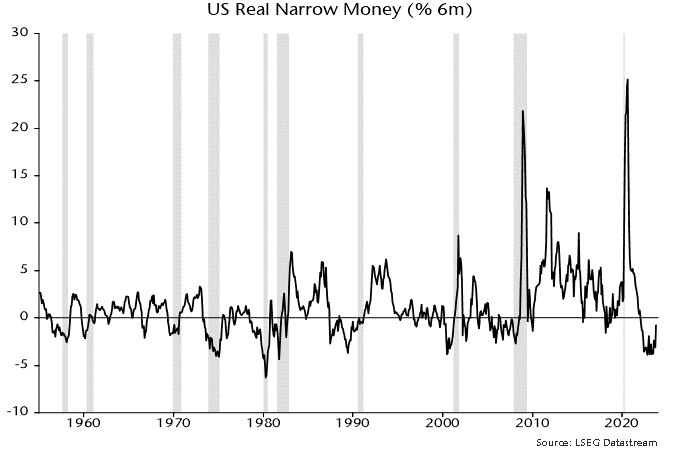

As chart 3 shows, it has been normal historically for six-month real narrow money momentum to start recovering before a recession hits or during its early onset.

Chart 3

One explanation for this relationship is that recessions are triggered by a sudden switch from spending to saving, with the latter reflected in an accumulation of liquid assets. A reversal of such “hoarding” in response to policy easing is a key driver of an eventual recovery.

So a further US monetary revival could both confirm an unfolding hard landing as well as laying the foundation for economic recuperation six to 12 months ahead.