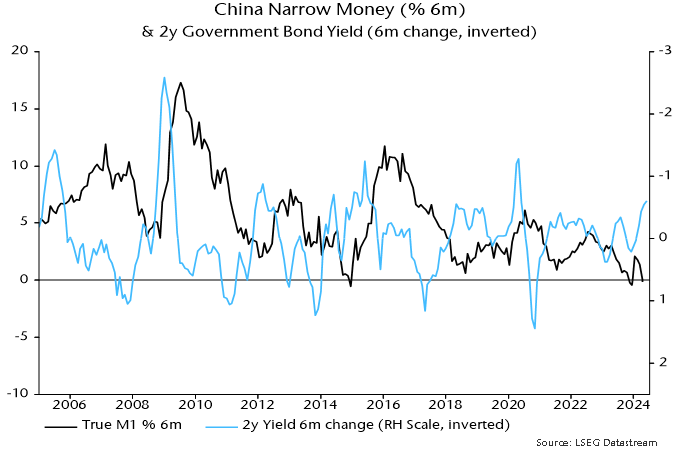

Chinese May money numbers were weak even allowing for a distortion from a recent regulatory change.

The preferred narrow and broad aggregates here are “true M1” (which corrects the official M1 measure for the omission of household demand deposits) and “M2ex” (i.e. M2 excluding bank deposits held by other financial institutions – such deposits are volatile and less informative about economic prospects).

Six-month rates of change of these measures fell to record lows in May – see chart 1.

Chart 1

April / May numbers, however, have been distorted by a clampdown on the practice of banks making supplementary interest payments to circumvent regulatory ceilings on deposit rates. This appears to have triggered a large-scale outflow from corporate demand deposits.

The April / May drop in six-month narrow money momentum into negative territory was entirely due to a plunge in demand deposits of non-financial enterprises (NFEs), with household and public sector components little changed – chart 2.

Chart 2

Where has the money gone? The answer appears to be into time deposits (included in M2ex) and wealth management products (WMPs), with a small portion used to repay debt.

NFE demand deposits contracted by RMB3.82 trillion in April / May combined. Their time and other deposits grew by RMB1.14 trillion over the same period. Total sales of WMPs with a term of six months or less, meanwhile, were unusually large, at RMB2.60 trillion, according to data compiled by CICC.

It has been suggested that banks were paying supplementary interest to meet lending targets – the additional payments gave NFEs an incentive to draw down credit lines while leaving funds on deposit at the lending bank (“fund idling” or “roundtripping” in UK parlance). Repayments of short-term corporate loans, however, were a relatively modest RMB0.53 trillion in April / May.

The appropriate response to regulatory or other distortions to monetary aggregates is to focus on a broadly-defined measure that captures shifts between different forms of money.

Chart 3 includes the six-month rate of change of an expanded M2ex measure including short-maturity WMPs. While momentum is stronger than for M2ex – and not quite at a record low – a decline since December 2023 continued in April / May, suggesting still-deteriorating economic prospects.

Chart 3