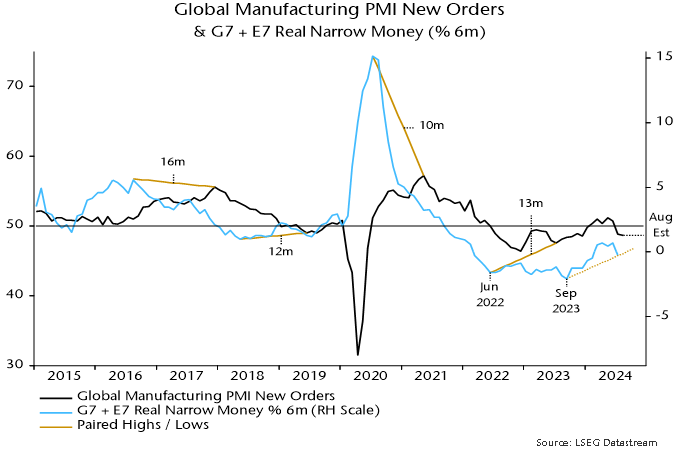

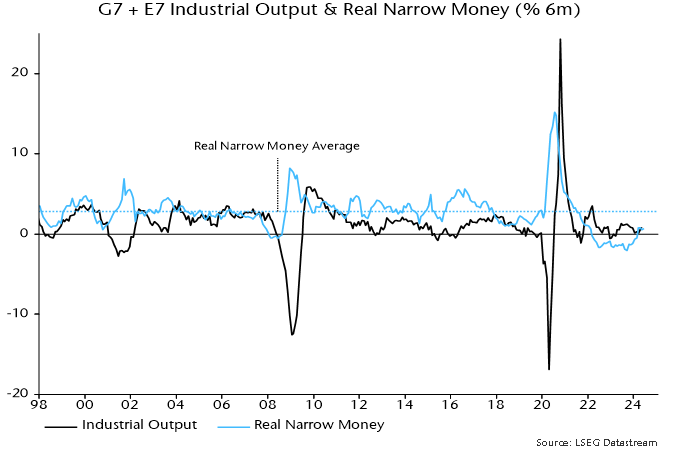

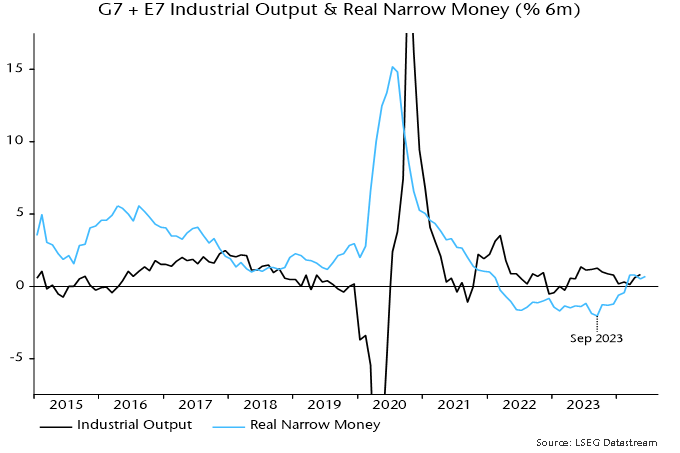

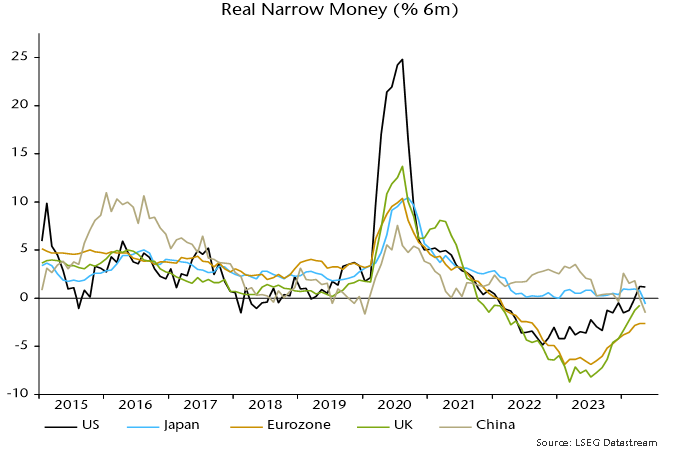

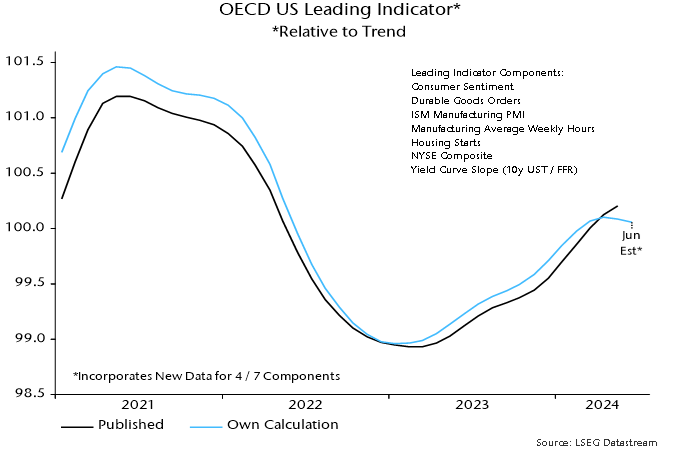

Global six-month real narrow money momentum is estimated to have moved sideways for a fourth month in July at a weak level by historical standards – see chart 1.

Chart 1

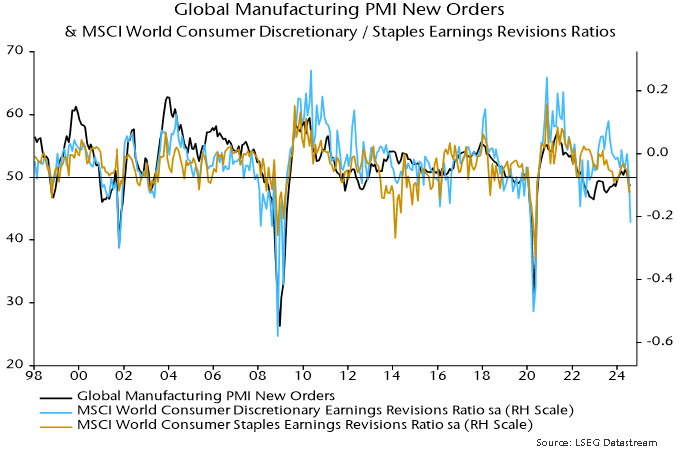

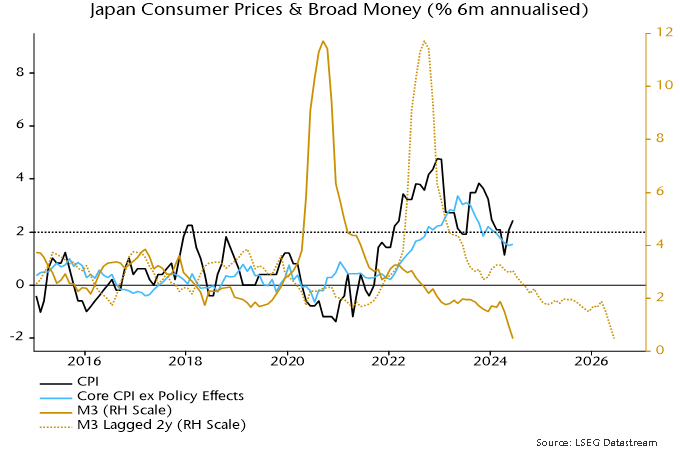

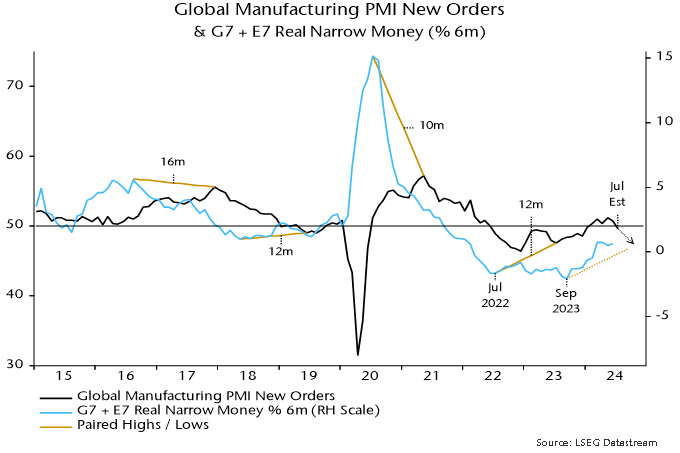

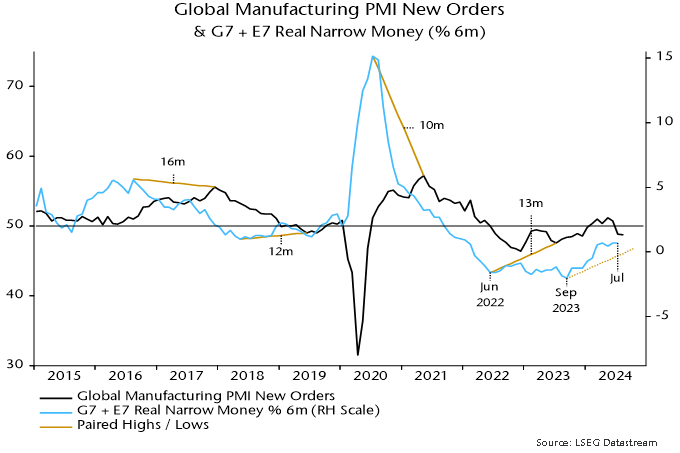

The baseline scenario here remains that global economic momentum – proxied by the global manufacturing PMI new orders index – will move down into late 2024, echoing a fall in real money momentum into September last year. Based on more recent monetary data, a subsequent recovery may prove limited, with weakness persisting well into H1 2025.

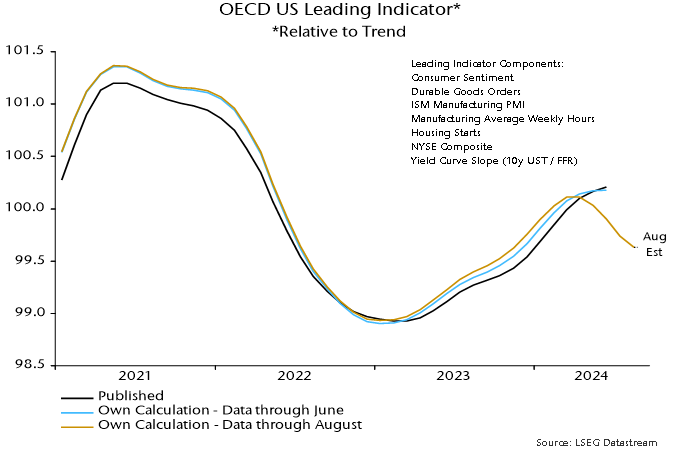

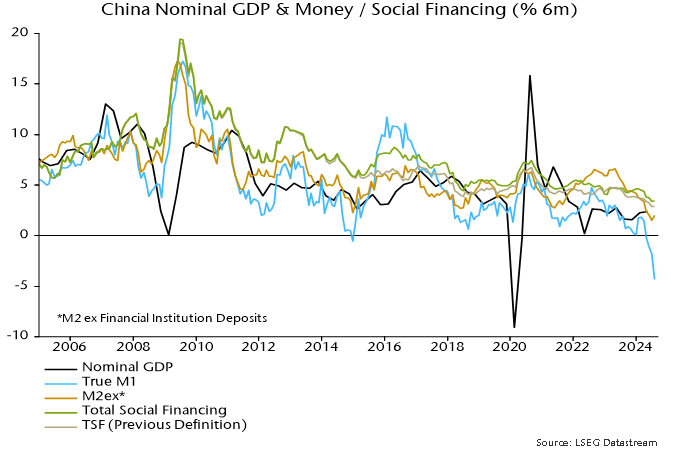

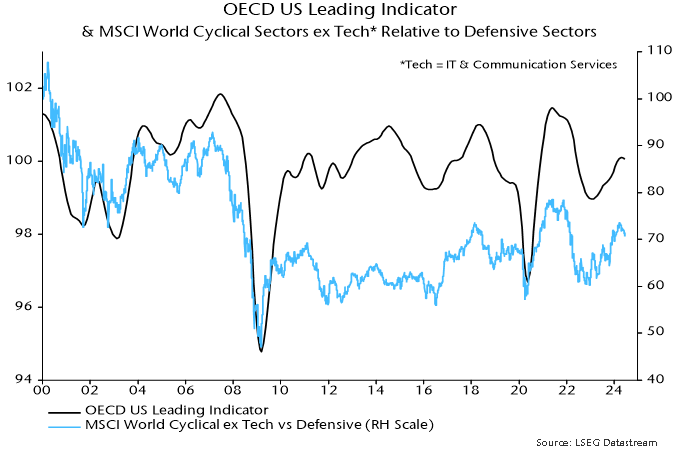

The unchanged July global real money momentum reading conceals a rise in the US offset by further weakness in China. The E7 ex. China component also cooled, while G7 ex. US momentum remained negative, moving sideways – chart 2.

Chart 2

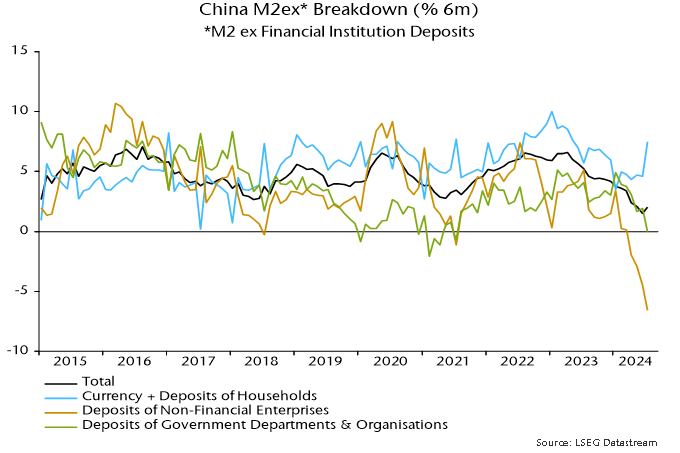

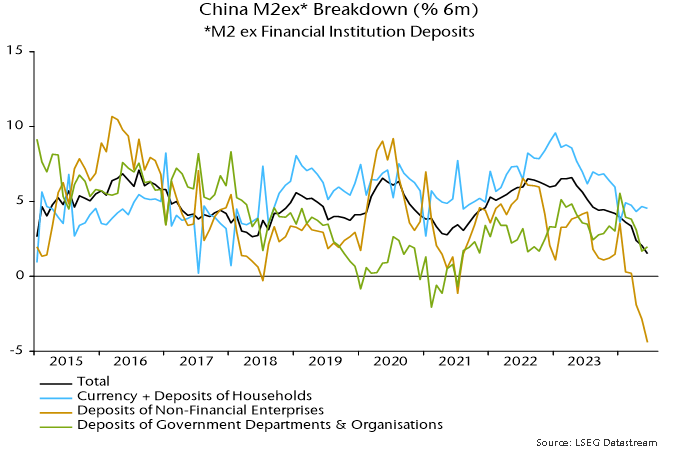

The Chinese series incorporates an adjustment* for a recent portfolio shift by non-financial enterprises from demand to time deposits in response to a regulatory change (a clampdown on payment of supplementary interest by banks). Chinese momentum would be significantly more negative without this adjustment, while the global series would be at its weakest level since February. (The adjustment may, however, underestimate the negative distortion to Chinese narrow money.)

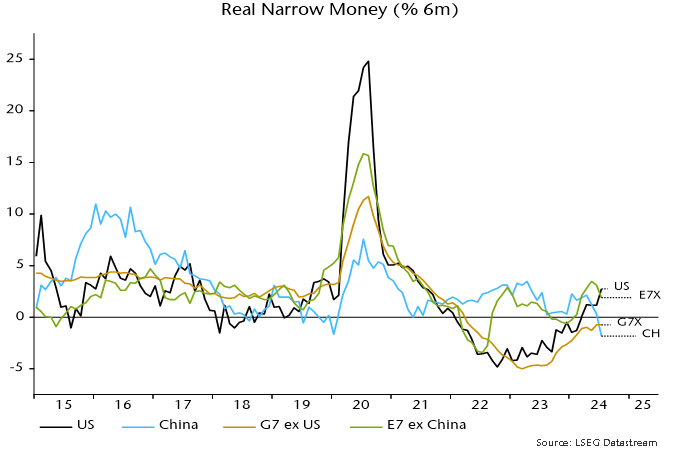

Chart 3 shows additional DM detail. Real narrow money momentum is relatively strong in Canada and Australia as well as the US.

Chart 3

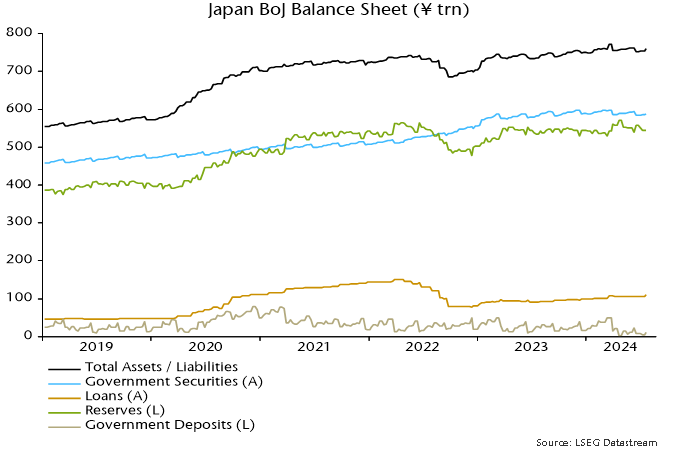

Japan moved deeper into negative territory but recent weakness partly reflects f/x intervention, so may abate.

Real money momentum is higher in the UK than the Eurozone but the difference is small, with both still negative. Recent UK economic outperformance is unlikely to last.

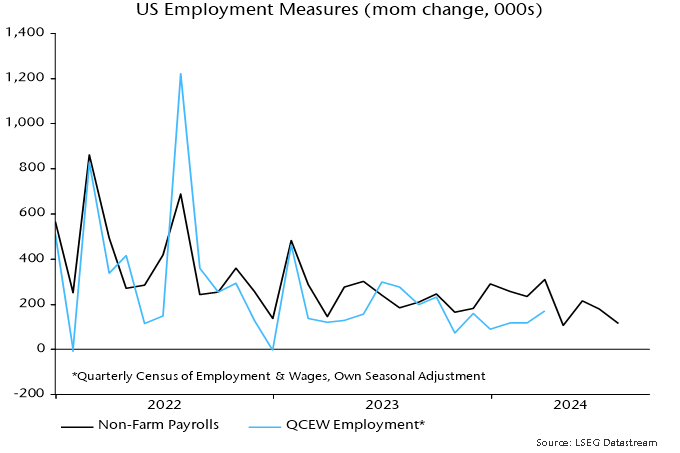

The pick-up in US real narrow money momentum suggests improving economic prospects but confirmation is required and lags should be respected.

The US July reading was boosted by a favourable base effect – narrow money contracted by 0.6% month-on-month in January. The base effect remains favourable for August but turns significantly negative in September / October.

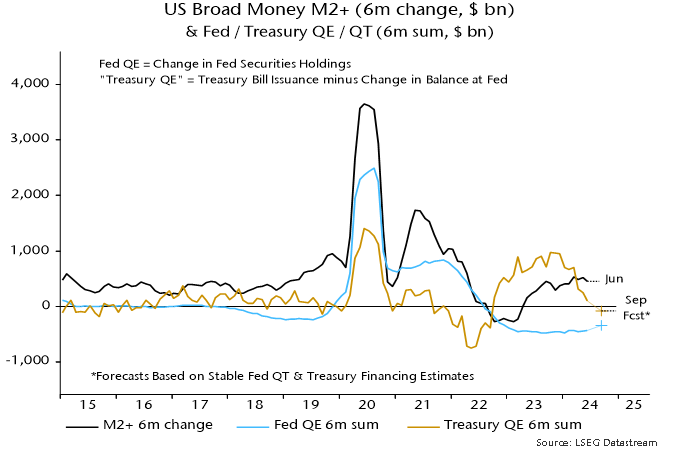

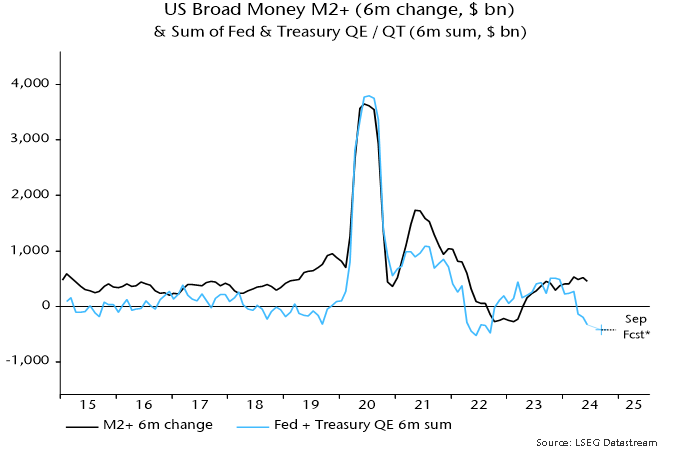

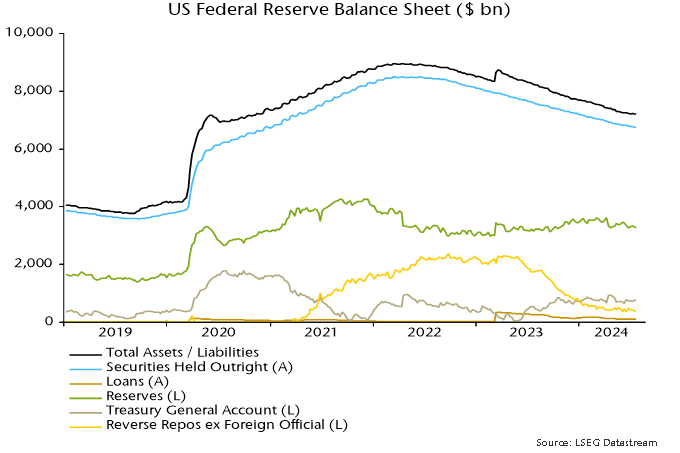

Six-month growth of US broad money is weaker than for narrow and has edged lower since May, though hasn’t yet fallen to the extent suggested by a contractionary shift in the joint influence of Treasury financing operations and Fed QT, discussed previously. The latest Treasury financing projections imply that this influence will turn expansionary again in Q4.

For perspective, US six-month real narrow money momentum had recovered to the current level in September 2008 as the financial crisis was reaching a crescendo with the recession having nine more months to run. In the prior 2001 recession, the current level was reached three months before the economy hit bottom. In both cases, the NBER business cycle dating committee had yet to determine that a recession had begun.

*The adjustment assumes that the share of demand deposits in total bank deposits of non-financial enterprises would have been stable at its March level in the absence of the regulatory change. The adjustment does not take into account any shift from bank deposits to non-monetary instruments (e.g. wealth management products) or effects on other money-holders.