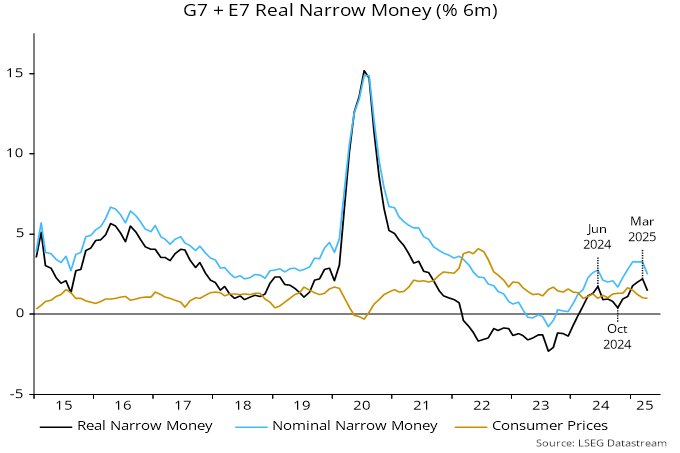

Global money growth has picked up since late 2024 but remains subdued, while the stock of money is no longer in excess relative to nominal economic activity and asset prices. The monetary backdrop, therefore, appears insufficiently supportive to offset economic / market damage from US-led tariff hikes.

Prospective tariff effects, meanwhile, require a revision to the previous forecast here of a downside global inflation surprise in 2025 related to extreme monetary weakness in 2023. A price level boost this year is unlikely to yield second-round effects given disinflationary monetary conditions, so a near-term lift to annual inflation should reverse in 2026. The effect may be to extend the lag between the money growth low of 2023 and the associated inflation low from two to three years.

The elimination of a surplus stock of money has been mirrored by erosion of excess labour demand, with job openings / vacancy rates mostly now around or below pre-pandemic levels. Economic weakness, therefore, may be reflected in a rise in unemployment that eventually dominates central bank concerns about inflationary tariff effects, suggesting that current policy caution will give way to renewed easing later in 2025.

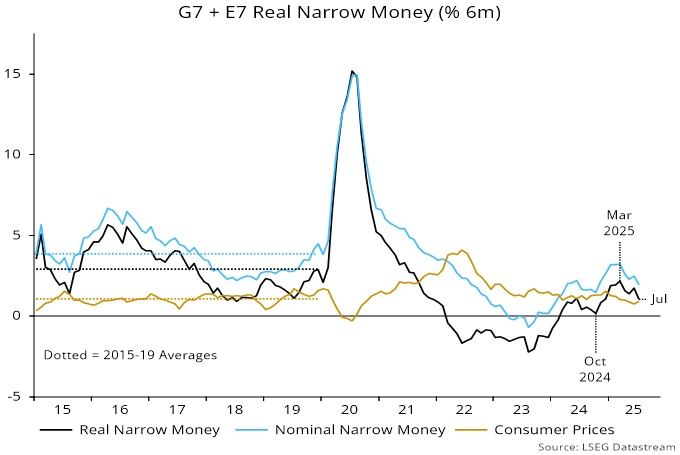

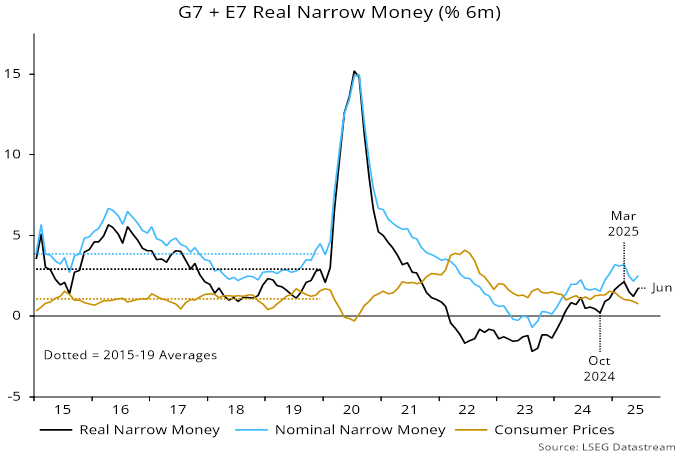

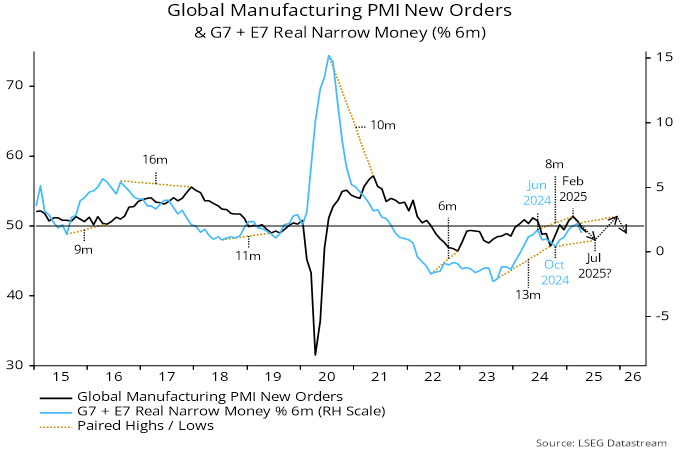

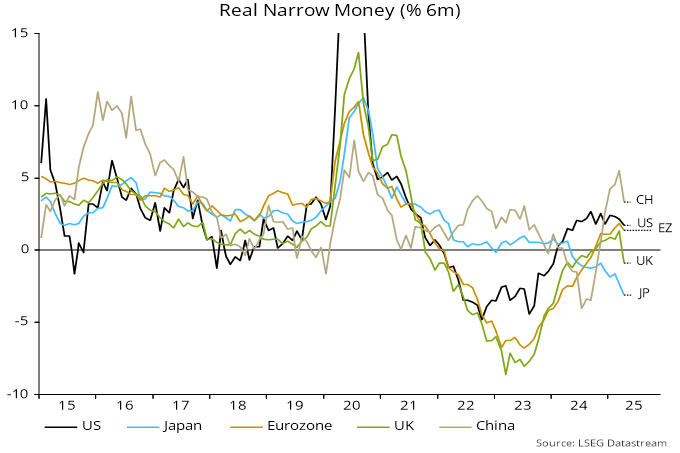

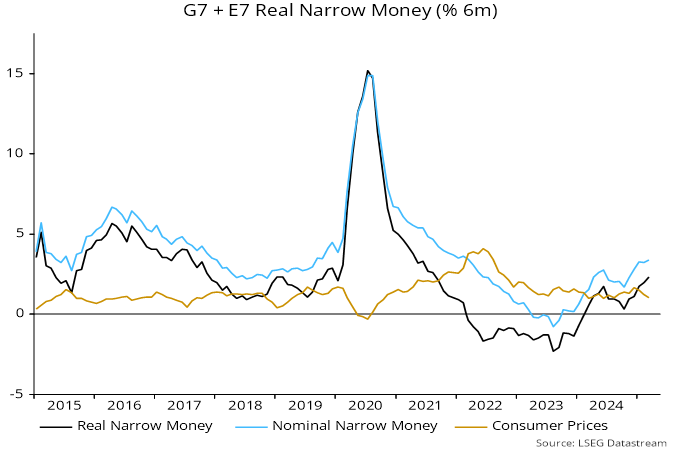

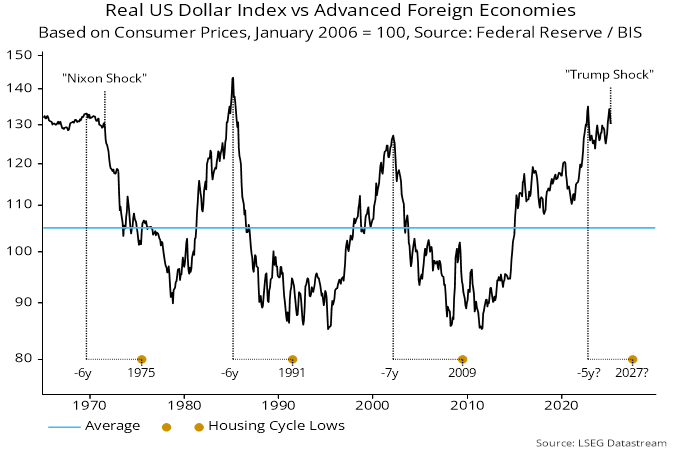

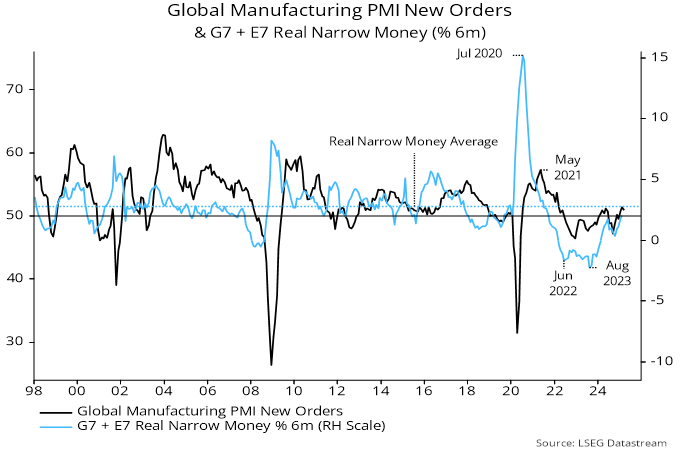

Global six-month real narrow money momentum – the key monetary leading indicator followed here – fell between June and October 2024 but has since rebounded, reaching a post-pandemic high in February. (The timing of the mid-2024 dip has changed slightly from previous posts, mainly reflecting annual revisions to seasonal adjustment factors for US monetary data.) Real money momentum, however, remains below its long-run average – see chart 1.

Chart 1

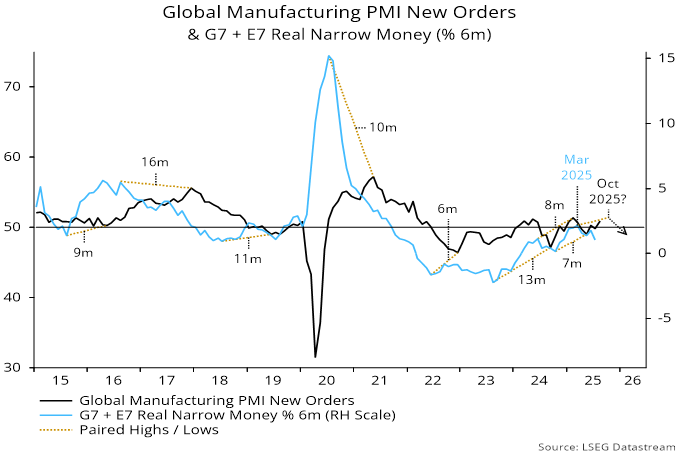

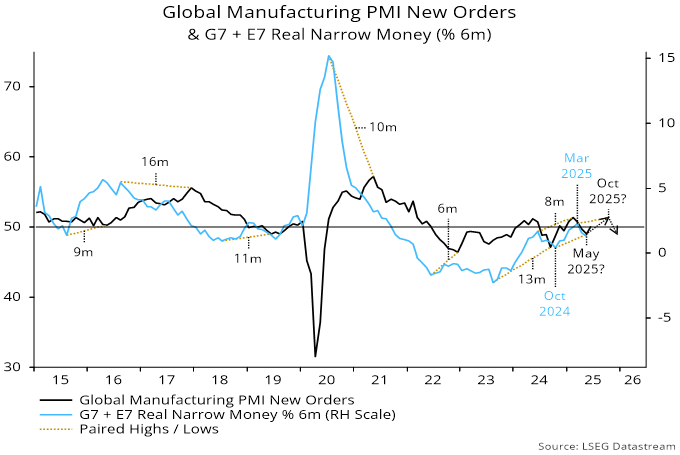

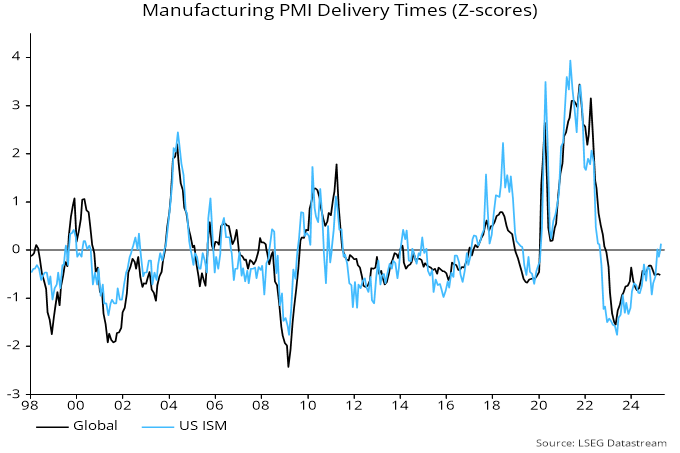

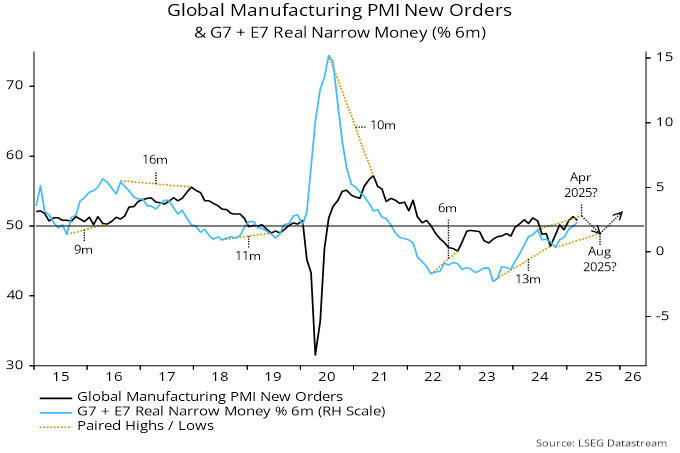

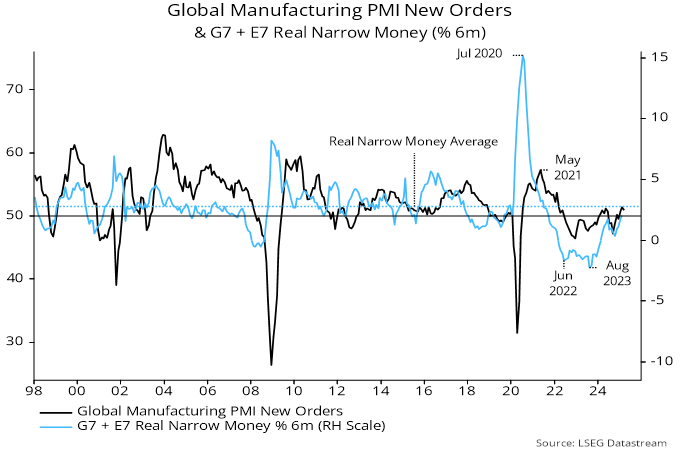

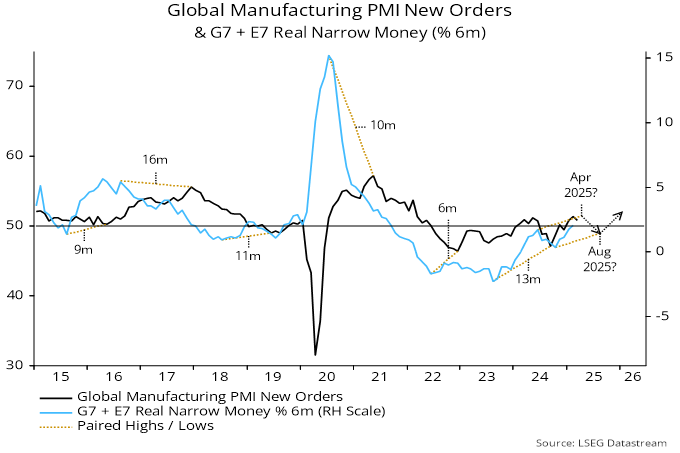

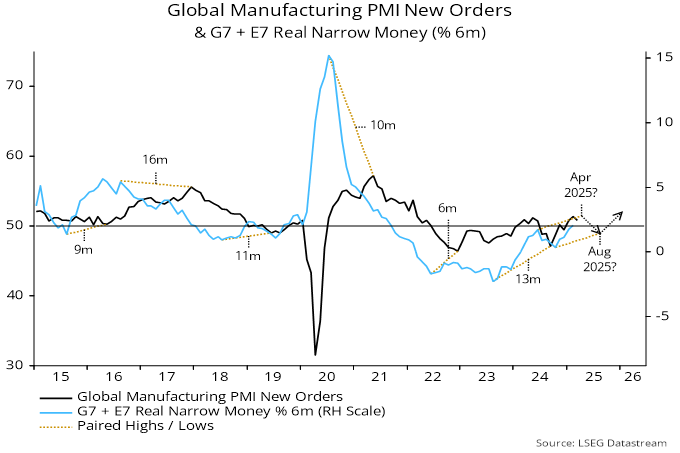

The lead time between real money momentum and manufacturing PMI new orders has averaged 10 months at the four most recent turning points. Based on this average, the 2024 real money slowdown and subsequent reacceleration suggest a PMI relapse in Q2 / Q3 followed by renewed strength in late 2025 – chart 2.

Chart 2

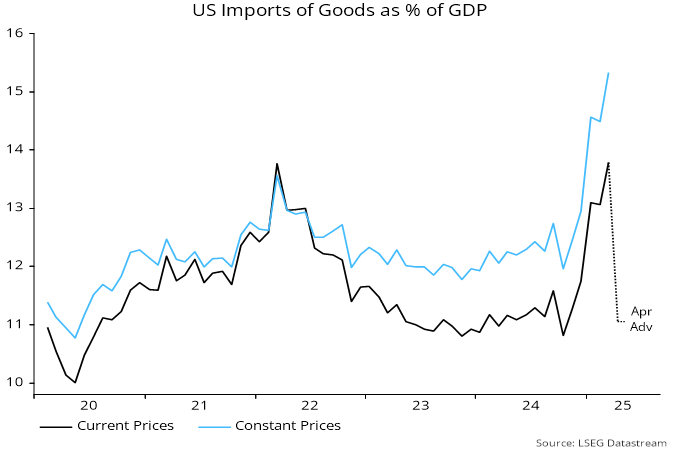

Tariff effects – including payback for a front-loading of trade flows – are likely to magnify mid-year economic weakness and could push out or even abort a subsequent recovery: delayed central bank easing, a confidence hit to business / consumer credit demand and a near-term inflation lift could reverse the recent pick-up in real money momentum.

Previous posts, meanwhile, argued that stocks of (broad) money in the US, Japan and Eurozone are no longer higher than warranted by prevailing levels of nominal economic activity and asset prices, implying an absence of a monetary “cushion” against negative shocks. Excess money appears to be substantial in China but could remain frozen as US trade aggression and domestic policy caution sustain weak business / consumer confidence.

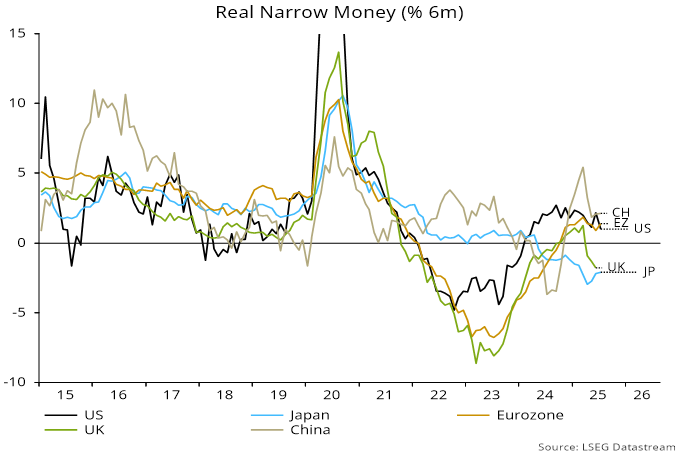

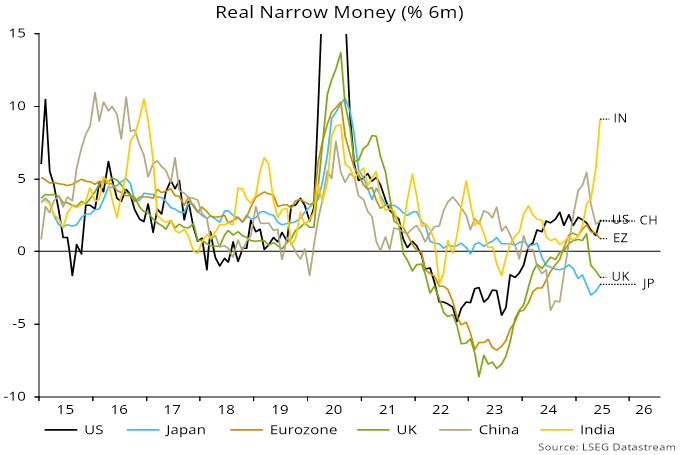

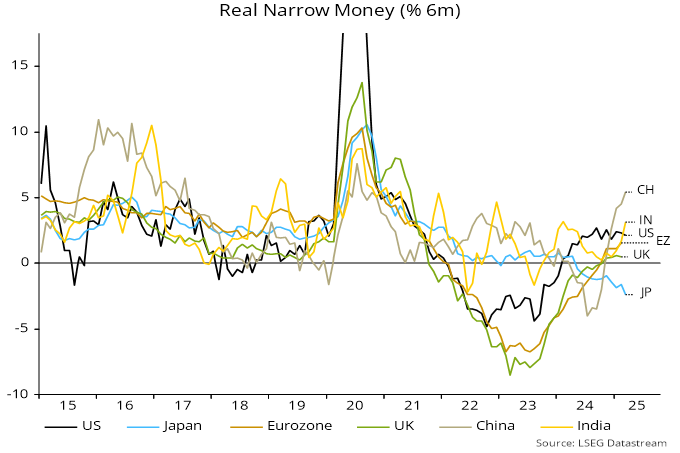

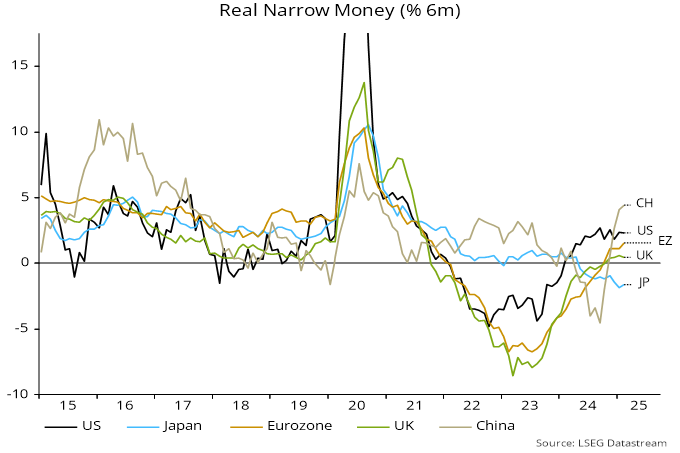

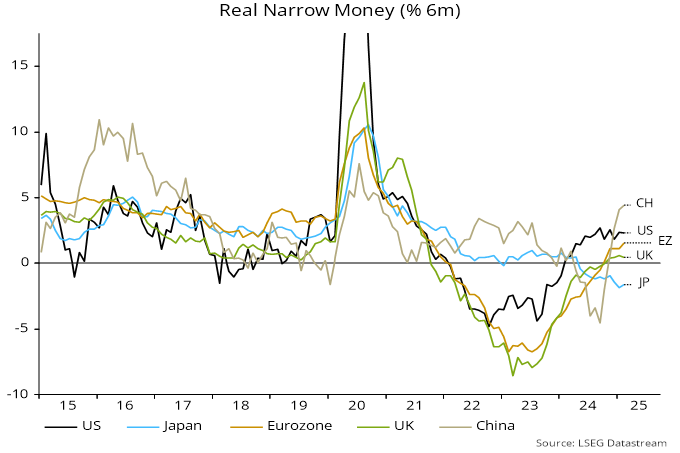

Chart 3 shows six-month real narrow money momentum in major economies. Chinese strength is a stand-out but may partly reflect payback for earlier weakness – momentum needs to remain solid to warrant continued (relative) optimism. A Eurozone recovery still leaves momentum lagging the US (where revised numbers show less of a recent slowdown), with the UK further behind. Japanese weakness is alarming, suggesting significant downside economic / inflation risk and consistent with recent lacklustre equity market performance.

Chart 3

European economic optimism has been boosted by a relaxation of German fiscal rules and a wider drive to increase defence spending. This is significant for medium-term prospects but has limited relevance for the near-term economic outlook, which hinges on whether an uplift from monetary easing will prove sufficient to offset trade war damage.

The two flow indicators of global “excess” money followed here are giving a mixed message: six-month growth of real narrow money has crossed above that of industrial output (positive) but 12-month growth remains below a long-term moving average (negative). This combination was associated with global equities slightly underperforming US dollar cash on average historically.

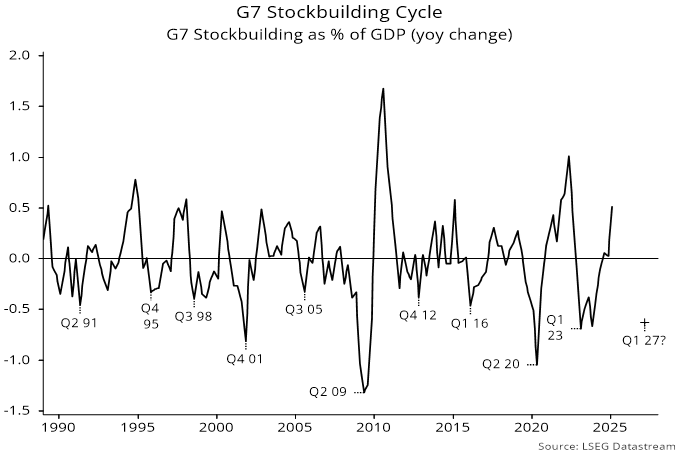

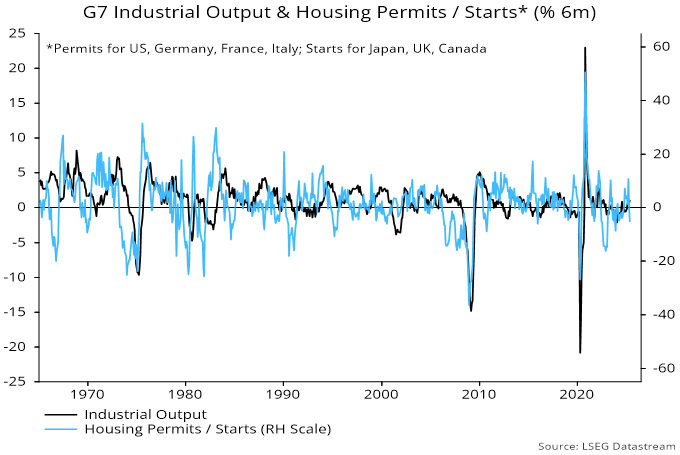

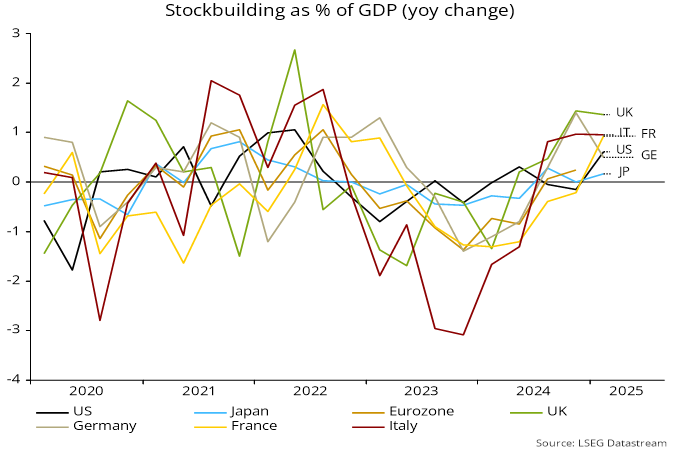

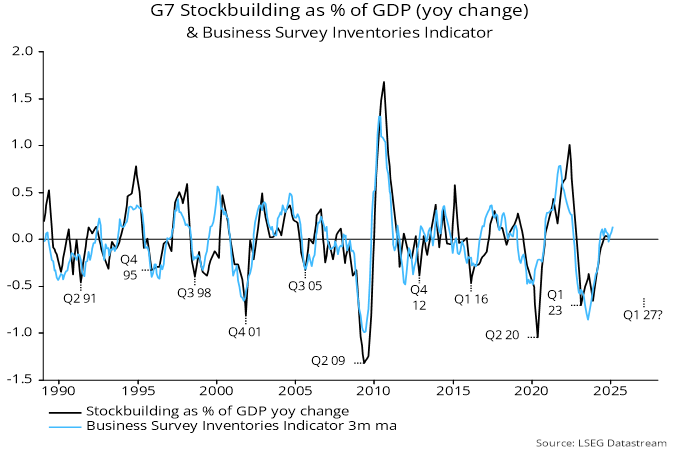

From a cyclical perspective, a key issue is whether the US tariff war shock brings forward peaks and downswings in the stockbuilding and business investment cycles, which are scheduled to reach lows in 2026-27 and 2027 or later respectively. The previous baseline here was that upswings in the two cycles would extend into 2026, a scenario supported by the current monetary signal of a rebound in economic momentum in late 2025.

The next downswings in the two cycles are likely to coincide with a move of the 18-year housing cycle into another low. Triple downswings are usually associated with severe recessions and financial crises. Such a prospect is probably still two years or more away but the US policy shock may have closed off the possibility of a final boom leg to current upswings before a subsequent crash.

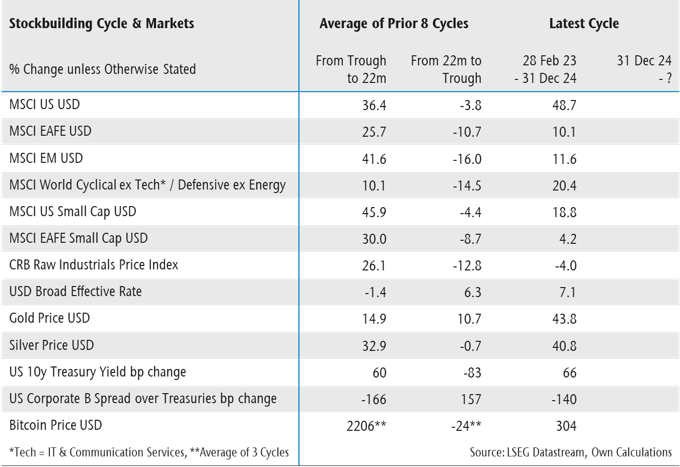

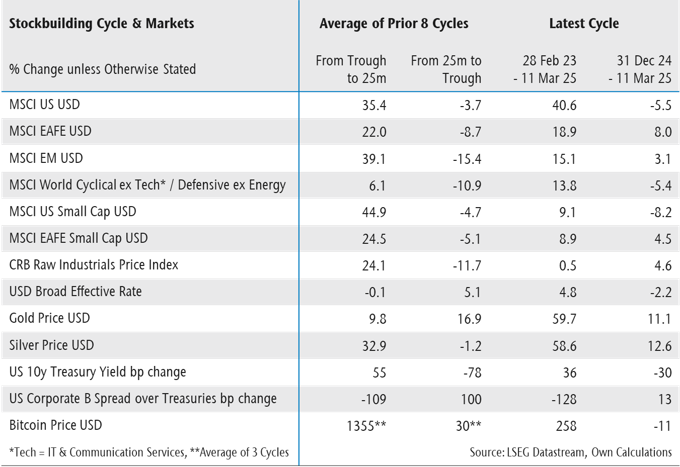

Table 1 updates a comparison of movements in various financial assets so far in the current stockbuilding upswing (which started in Q1 2023) with averages at the same stage of the previous eight cycles, along with changes over the remainder of those cycles. Three months ago, US equities, cyclical sectors, the US dollar and precious metals were performing much more strongly than average, suggesting downside risk. By contrast, EAFE / EM equities, small caps and industrial commodities appeared to have catch-up potential.

Table 1

Q1 moves corrected some of these anomalies, with the US market falling back, Chinese / European equities performing strongly, US cyclical sectors lagging, the dollar falling and industrial commodity prices recovering. Precious metals, however, became even more extended relative to history, while small cap performance has yet to pick up.

The updated table suggests potential for further strength in EM and to a lesser extent EAFE equities, along with industrial commodities. Cyclical sector underperformance and dollar weakness could extend, while gold / silver appear at high risk of a correction. The larger message, however, is that, even assuming a delayed peak, the stockbuilding cycle has entered the mid to late stage that has been unfavourable for risk assets historically.

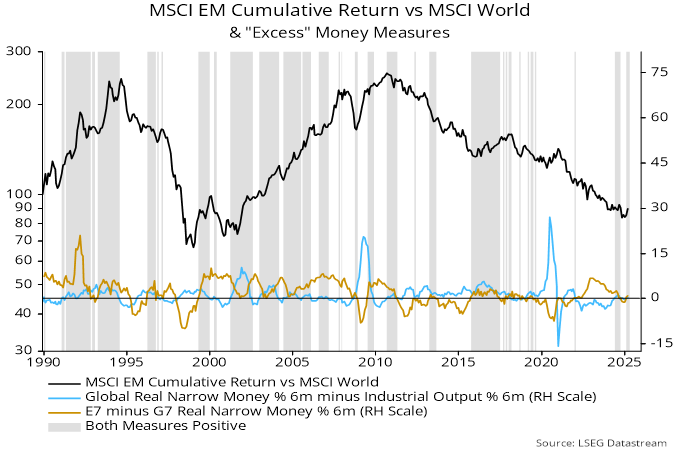

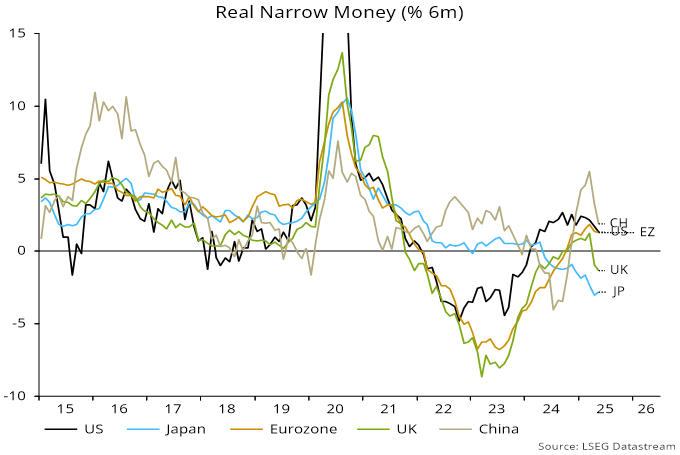

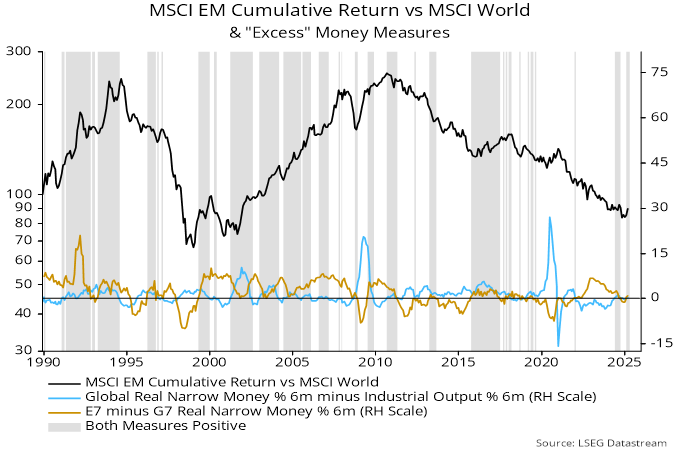

The suggestion of EM outperformance is supported by monetary considerations. Six-month real money momentum is stronger in the E7 large emerging economies than in the G7, while – as noted earlier – global real money is outpacing industrial output. EM equities beat DM on average historically when these two conditions were met, underperforming in other regimes – chart 4.

Chart 4