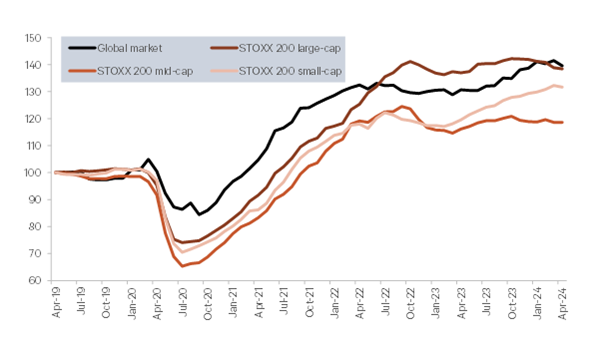

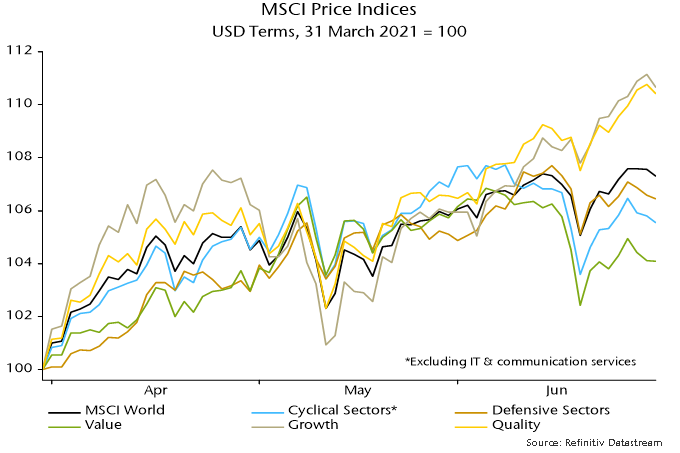

International stock markets performed well for most of the quarter although the potential implications of President Trump’s trade tariffs began to weigh on equities in the second half of March. The EAFE index returned +2.89% in local currency terms, with a larger gain of 6.86% in US dollars. The positive headline result, however, conceals significant style / sector rotations, with growth, quality, IT and consumer discretionary underperforming but strong gains for high dividend yield / value stocks and some defensive areas. Utilities, energy, financials and communications were the best-performing sectors over the quarter delivering double-digit returns.

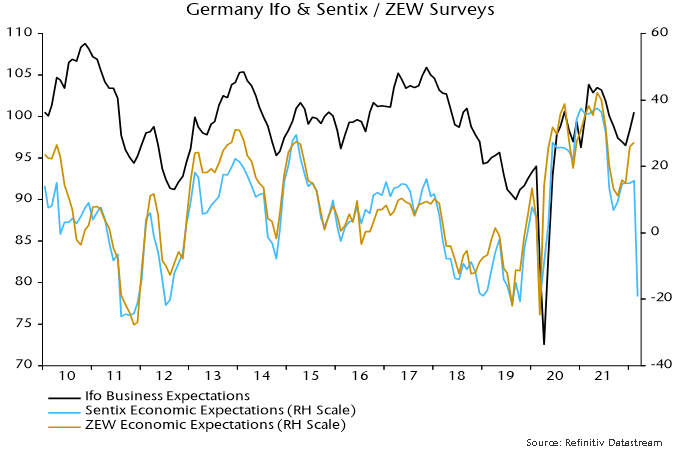

These moves reflected macroeconomic developments, in the form of Germany’s announcement of a major medium-term loosening of fiscal policy and signals from the US administration of a determination to press ahead with the imposition of high tariffs on imports. The German fiscal news, reinforced by an EU commitment to increased defence spending, spooked bond markets, with the 10-year Bund yield jumping by 0.5 pp to retest its September 2023 high. Higher yields dragged down growth and quality, while helping to sustain strength in financials. Rising expectations of significant reciprocal tariffs, meanwhile, contributed to weakness in consumer discretionary.

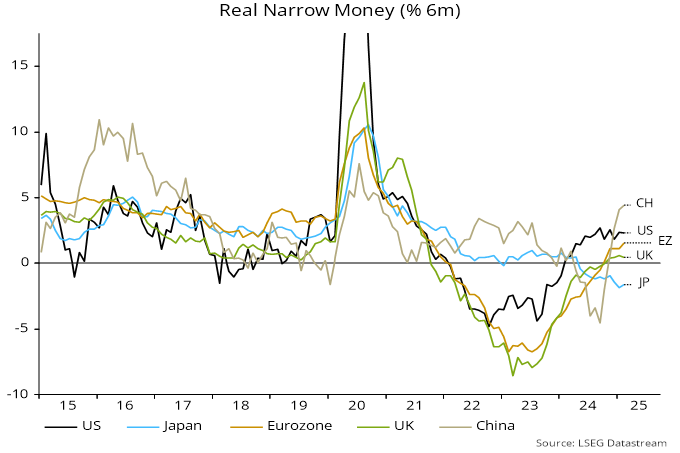

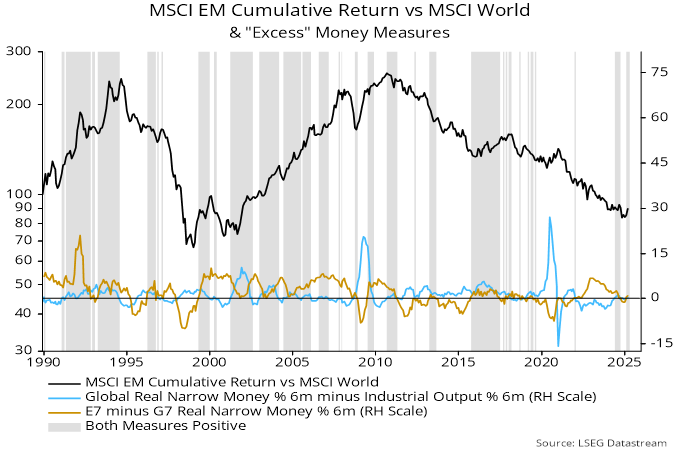

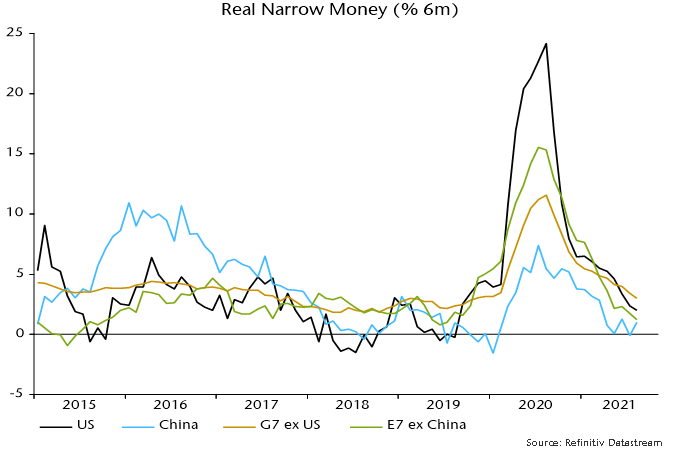

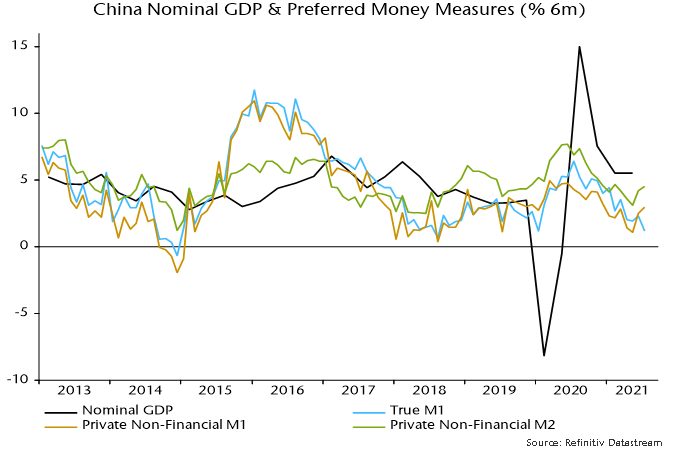

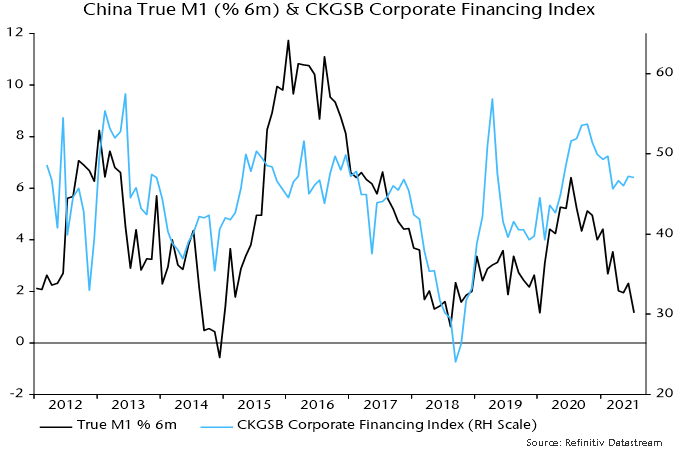

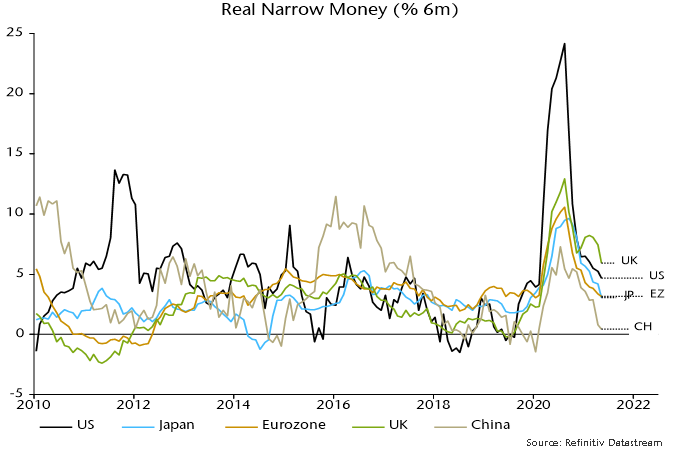

In Asia real money growth is up in China but lagging in Japan. We continue to believe that the domestic Japanese economy is vulnerable due to policy missteps by the Bank of Japan in raising interest rates. Headline inflation has been boosted by food prices and the lagged impact of yen weakness, but the core rate is sub-2% and likely to fall further. We favour overseas earners remaining underweight domestically orientated stocks. Despite a strong run, Chinese stocks appear inexpensive relative to other emerging markets while the EM asset class looks more attractive relative to the US; our checklist of emerging versus developed market indicators is at its most positive for many quarters.

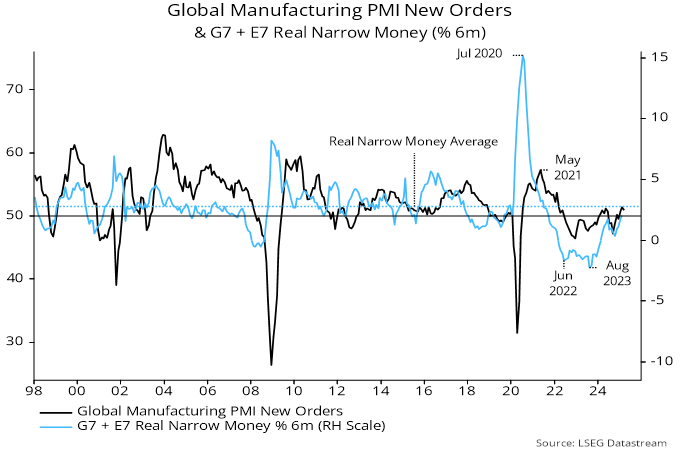

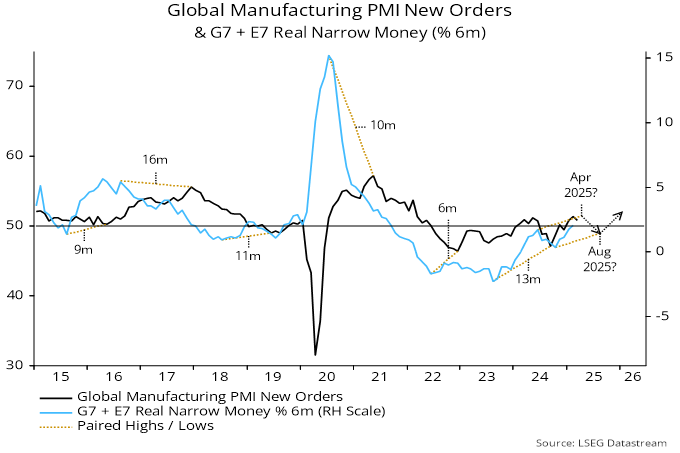

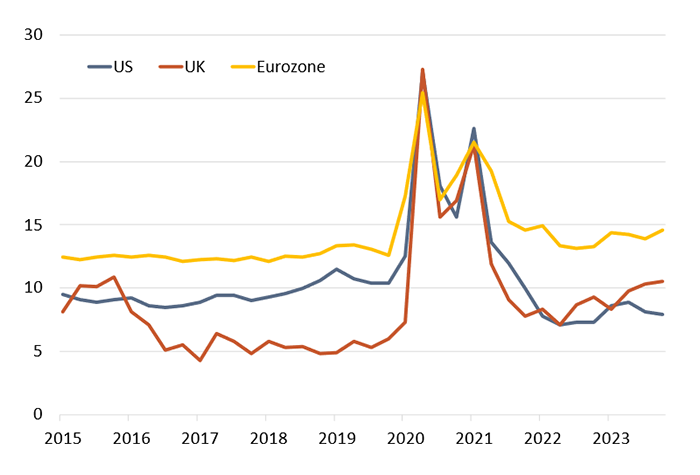

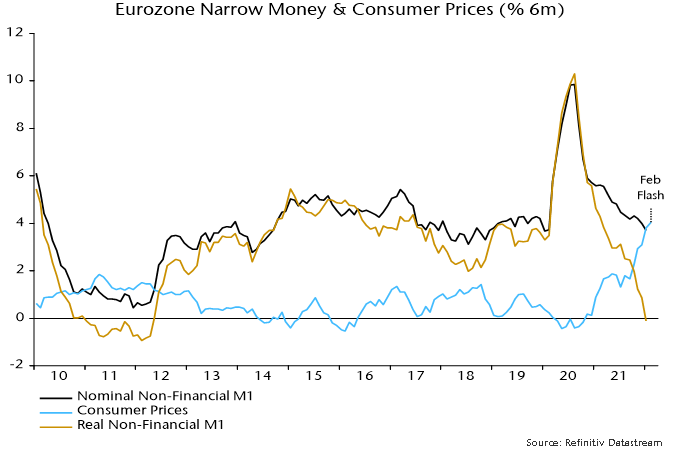

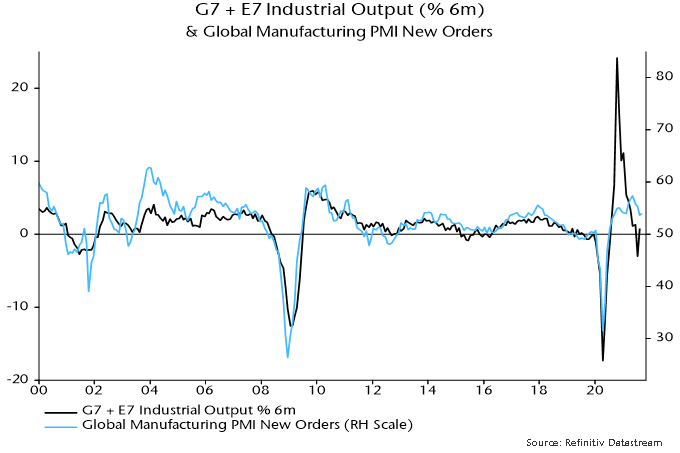

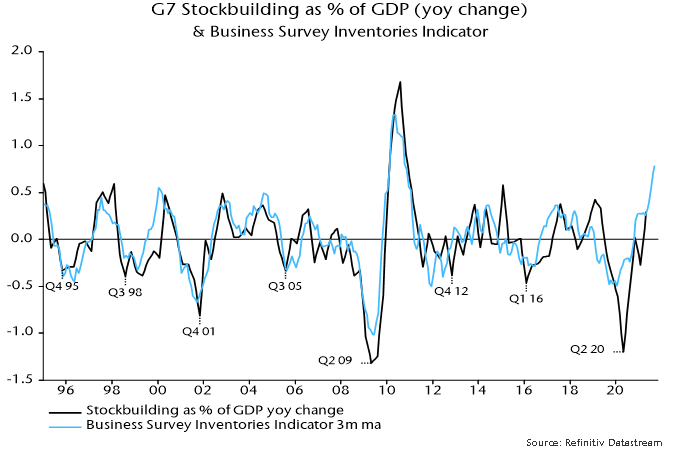

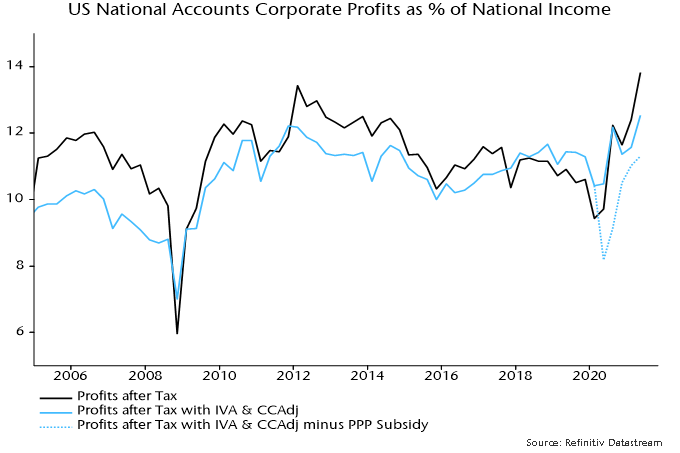

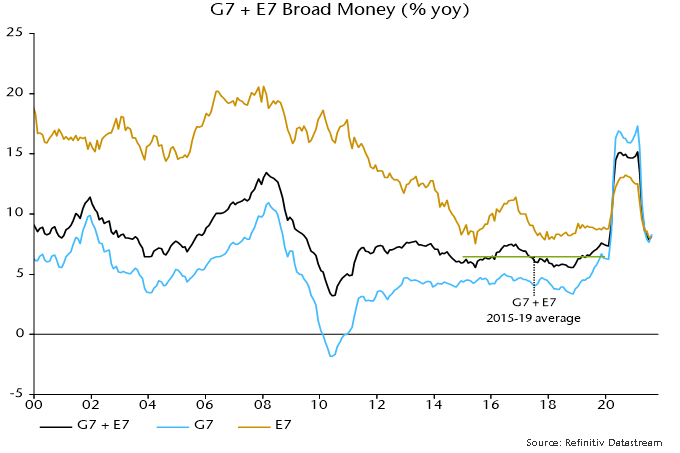

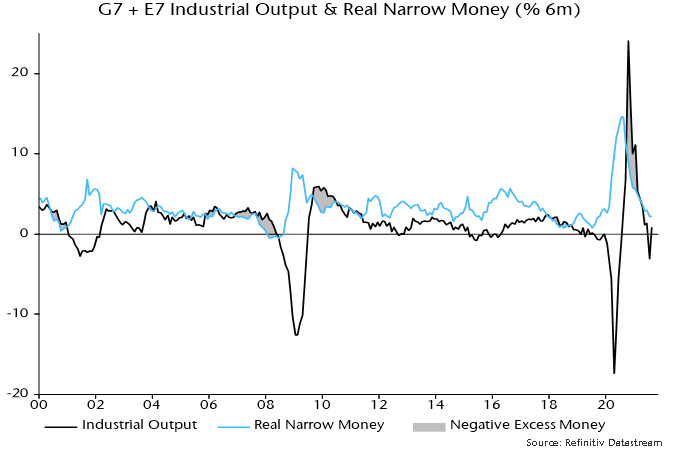

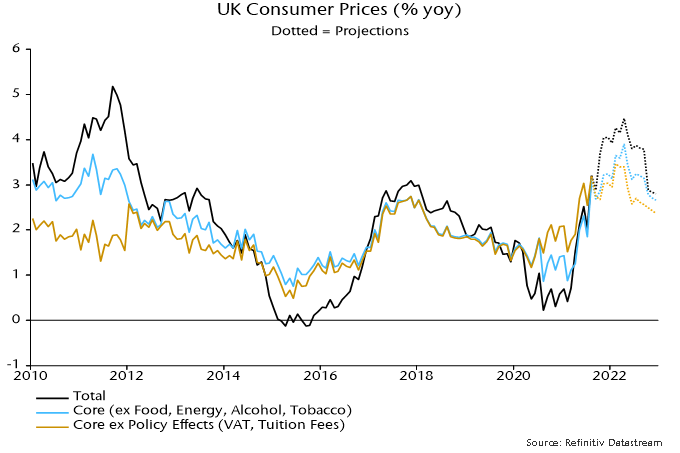

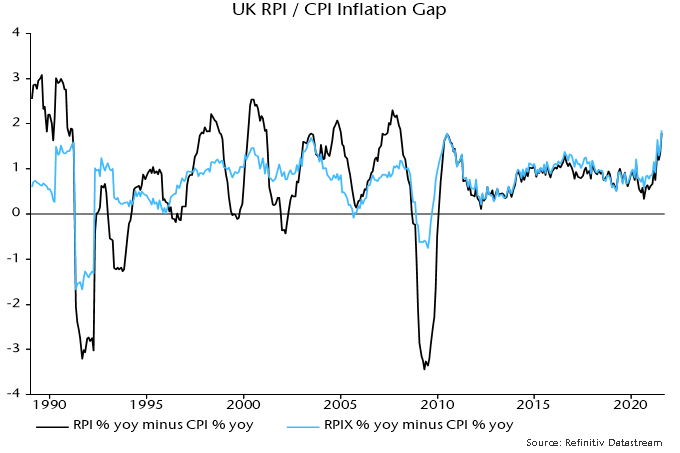

Our monetary indicators have been suggesting a loss of global economic momentum in Q2 / Q3 2025 followed by a reacceleration in late 2025. The imposition of US tariffs at a higher-than-expected level, with strong probability of reciprocal actions, will magnify near-term weakness and could push out or abort a subsequent recovery. Planned German / Eurozone fiscal loosening is significant for medium-term prospects but will provide limited support this year. Despite a mechanical inflation impact from tariffs, central banks are likely to come under greater pressure to ease policies to limit a rise in unemployment. We would expect this scenario to be associated with stable or lower longer-term bond yields and an associated recovery in growth / quality and some defensive areas. Tariffs, meanwhile, are likely to inflict greater economic damage on the US than its major trading partners, inclining us to avoid US economic exposure in favour of the Eurozone / China, where monetary recoveries have continued, and the authorities have policy space to offset tariff damage.

Stock and sector selection were both negative as volatility rose in the latter part of the quarter. The overweight in IT and underweight in defensive sectors such as utilities and energy were negative as was the underweight in financials. Stock selection disappointed across regions as the growth and quality factors lagged value and high yield. In healthcare Danish insulin giant Novo Nordisk (-20%) was weak as efficacy trials on its new generation of diabetes drugs disappointed; by contrast, Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche (+20%) re-rated as its drug pipeline momentum improved. Japanese optics specialist Hoya (-11%) also underperformed within the sector, reflecting its exposure to the semiconductor industry. Performance was weak in industrials as Schneider Electric (-9%) continued to be de-rated due to its exposure to data centres even though this represents just 20% of the business. Negative sentiment towards data centres after the Deepseek release also impacted Australian real estate play Goodman (-20%) and partly explains the fall in Australian investment bank Macquarie Group (-11%). Investors questioned the previous optimistic outlook for energy demand driven by AI use.

Stock picks were better in consumer discretionary where Sony outperformed on announcement of an additional buyback and strong Q3 results in which games were a stand-out. European defence stocks such as Thales (+84%) received a boost as governments signalled an increase in spending to compensate for a reduced US commitment to NATO, while Germany’s easier fiscal plans helped cement maker Heidelberg Materials (+37%) and Nemetschek (+19%), which provides software for the construction industry. In financials Caixabank (+43%) benefited from loan growth in a strong Spanish economy.

Portfolio activity over the quarter has tactically increased exposure to stocks benefitting from a European recovery. These include the purchase of Heidelberg Materials and Siemens in Germany, insulation specialist Kingspan in Ireland and electric power tool maker Makita which is listed in Japan but has significant sales in Europe. We have reduced the underweight in financials with the purchase of Caixabank in Spain which has a powerful franchise across product categories with a strong capital return story. We have also added Commerzbank in Germany. In Japan we introduced Softbank where we like its largest asset, chip designer Arm, listed in the US. We have also bought Fanuc which is a global leader in factory automation and should benefit from the relocation of supply chains.

On the sell side we have reduced stocks with significant US economic exposure, including Compass Group, Experian and exited Ashtead in the UK and Recruit in Japan. We have lowered staples with the sale of Lindt and reductions in Unilever and Nestle. Blood plasma specialist Csl has been exited in Australia as has Samsung in Korea. We have sold lottery operator OPAP in Greece to fund the purchase of Bank Pekao in Poland.

The portfolio is overweight Europe versus underweights in Japan and Asia ex Japan. We favour software, insurance and luxury goods against underweights in retailers and banks while we continue to be zero weighted autos and miners. Better economic activity in Europe in 2026 should help cyclicals and we like stocks with eastern European exposure which should benefit from any ceasefire in Ukraine and subsequent reconstruction. As mentioned, our EM checklist is more favourable and we are looking for opportunities to add in the event of tariff-driven weakness.

We believe US tariffs, whether reciprocated or not, damage the US more than most other countries because of a higher affected share of GDP. A tariff boost to inflation will likely be modest and temporary. Policy easing in the rest of the world will be stepped up while the Fed waits. This favours further outperformance by EAFE markets. The Trump presidency has driven a rise in volatility and uncertainty with investment decisions seeming logical one day and misplaced the next, impacted by the noise created by the administration. We believe a disciplined, systematic approach focused on quality businesses with strong financials is the best defence in the current environment. Our focus remains on companies achieving a high or improving return on invested capital with good margins and pricing power that can weather the economic and political storms ahead.

The Composite rose by 1.79% (1.64% Net) versus a 6.86% rise for the benchmark.