Summary

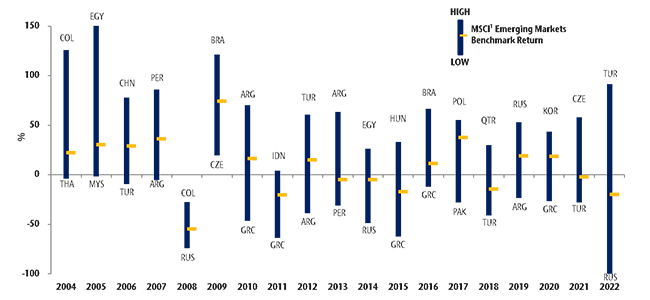

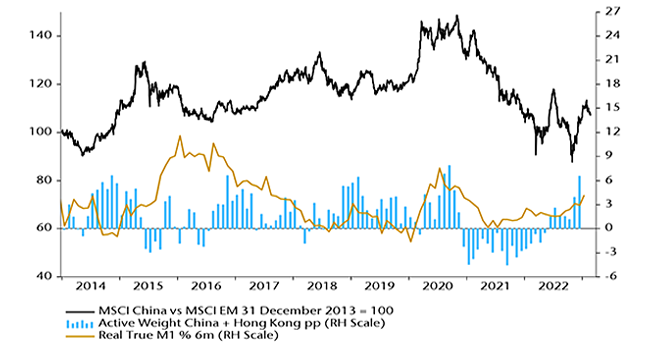

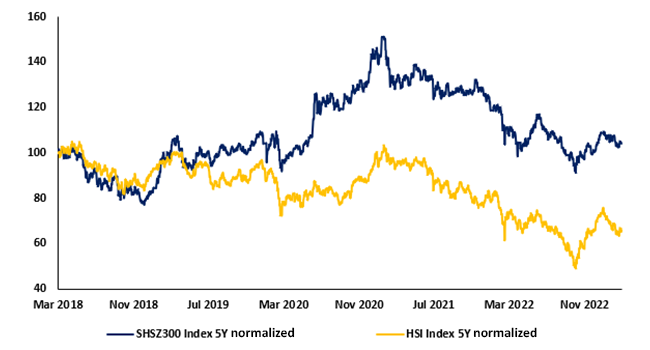

- EM equities were down through the month, with China the key drag as investors were disappointed by weaker than expected consumption figures.

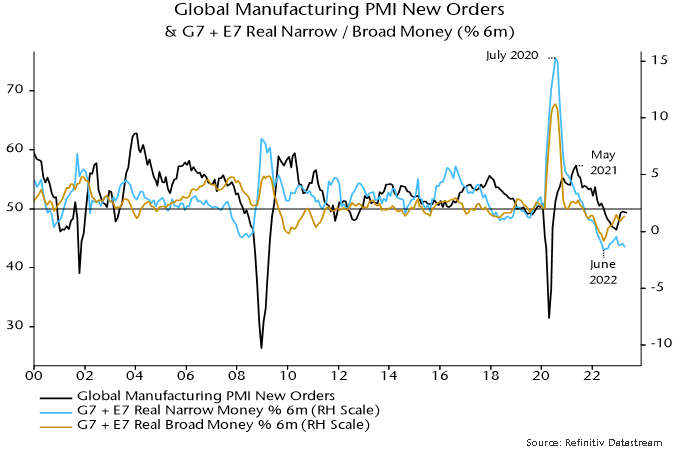

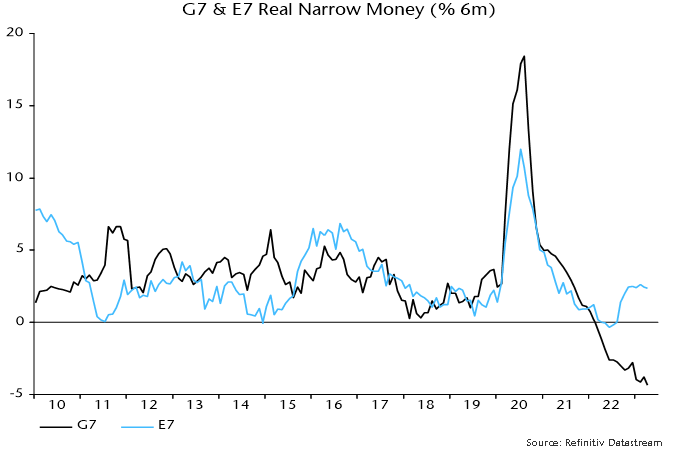

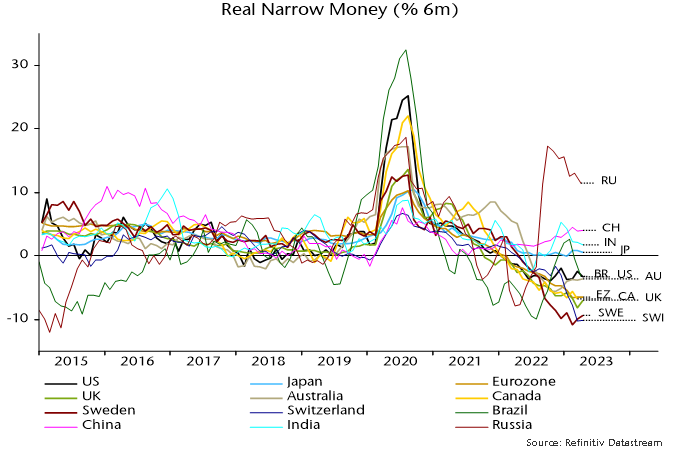

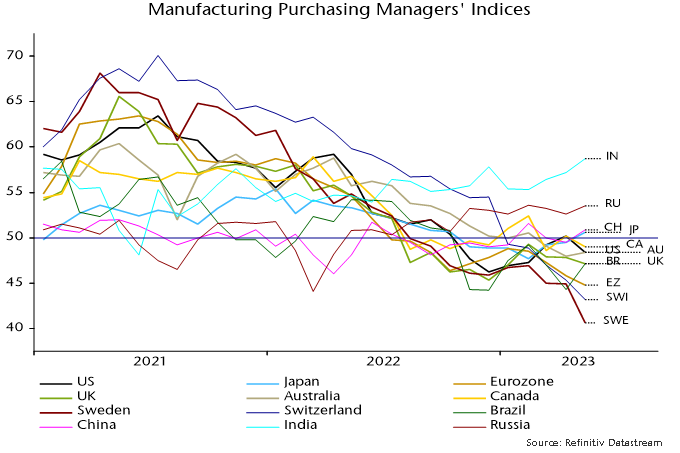

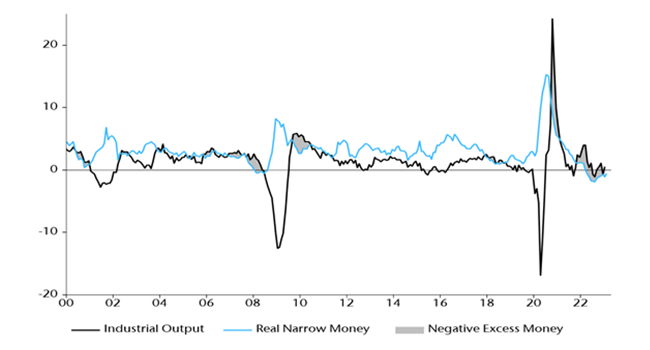

- Cyclical markets exposed to energy and commodities including the Gulf states and South Africa posted negative returns. Our view is that these parts of the market will remain vulnerable as the global economy deteriorates on the back of very weak money numbers.

- Pro-democracy parties swept Thailand’s national elections, led by the progressive Move Forward Party which is set to form a governing coalition with Pheu Thai and four other smaller parties. However, a Senate dominated by figures appointed by the military government that seized power in a 2014 coup threatens to delay the appointment of the governing coalition and the appointment of Move Forward’s leader Pita Limjaroenrat as Prime Minister. Uncertainty will hang over Thai equities as the tussle between the coalition and the Senate plays out in the coming months.

- Despite unorthodox economic policy sparking surging inflation and a collapsing economy, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan secured a third decade in power, winning a second round run-off against opposition coalition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

- Semiconductor names in Taiwan and Korea surged on the investor frenzy over AI technology sparked by Nvidia reporting Q1 sales and management guidance which were streets ahead of sell-side expectations.

India remains one of the best structural stories in EM

NS Co-CIO Ian Beattie returned from a research trip in India this month, and he was keen to emphasise that the story of India’s rapid rise is still on:

“My thesis that this still feels like China 30 years ago is intact. Now imagine that with strong institutions and democracy. Of course, we are dealing with a massive and diverse country – you have to embrace the mess, chaos, bureaucracy, the riots, shocking Gini coefficient and all that entails. BUT, it is improving in almost all of the important areas. And you make money on the delta, don’t you?

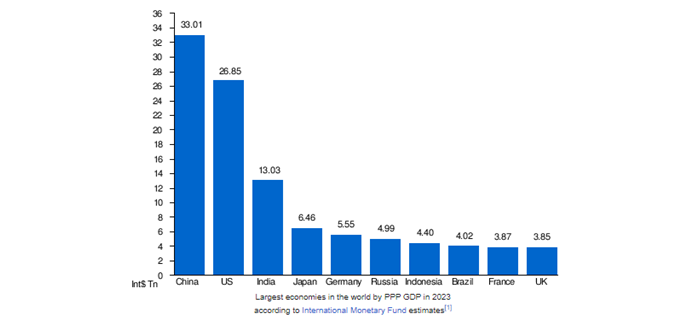

India as the fastest growing major economy has grabbed headlines but it is ongoing. Structural reform, societal change (slow), tax and social reform (incredible), it feels like a virtuous circle. United Payments Interface (UPI) is now a success on a global scale.

Sustained progress buttressed the popularity of Prime Minister Modi, liked by the poor as well as the shopkeepers. The poor and middle classes are getting wealthier and feel that there is less skimming from the top.

Infrastructure is improving, employment is up. Tax collection is up. It feels like things are improving for almost everyone.

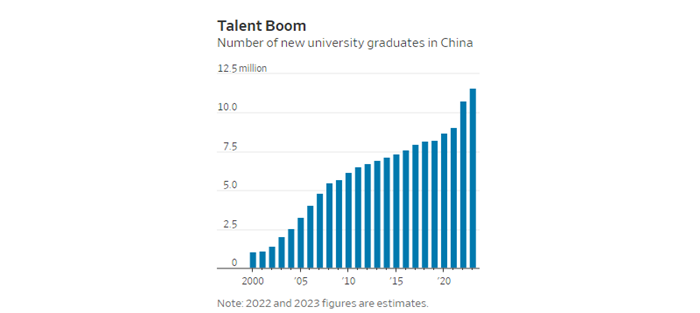

I am seeing first-hand the increasing aspirations in younger generations. Though it will be a challenge for the government to stay ahead of this I imagine it opens up a completely new political landscape and many opposition parties will be unable to resort to traditional tactics.

Indian stocks are relatively less expensive than on my last visit, having traded lower and recovered to similar levels, whilst very strong GDP growth and good earnings have come through.

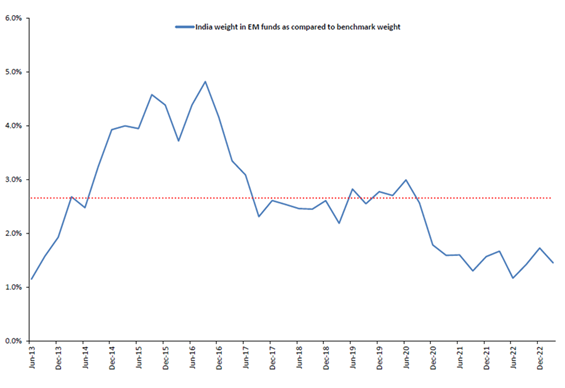

Foreign investors in Indian equities are back to a very small overweight, while locals fear a retreat by retail investors as positive momentum has faded.

Foreign investor positioning – modest overweight

Source: Jefferies, 2023.

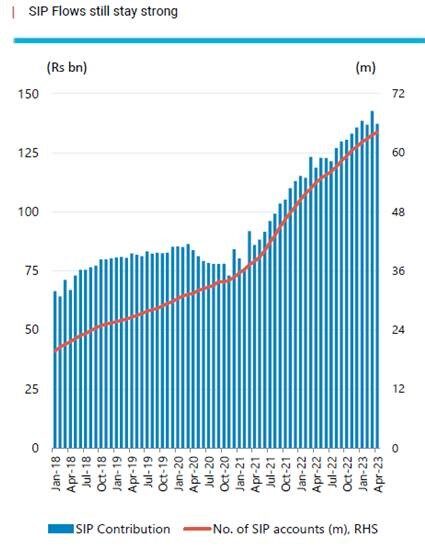

However, this misses the structural story at play which is becoming increasingly important – that is the rising importance of domestic flows from local mutual funds seeing inflows from Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs).

Structural change in EM can be a key return driver

Source: Jefferies, 2023.

Flows from a young and growing cohort into domestic mutual funds are boosting local liquidity, with long time horizons suited to equities exposure and more incentivised than foreign investors to push on Indian corporates to improve governance.

Be careful of relying too much on your mean reversion tables when structural change like this is underway. Prices are no longer set in London or New York, but rather in Delhi or Mumbai.”

India’s embrace of digital payments infrastructure is supercharging its development

India is a country of 1.4 billion people, 22 languages, 1 billion mobile connections and 800 million internet users. Yet only 6% are income taxpayers and only 6% transact digitally for commerce.

Leveraging technology and widespread connectivity is seen by policymakers as a massive development opportunity to draw more people into the formal economy while supporting innovation and relieving economic bottlenecks in India.

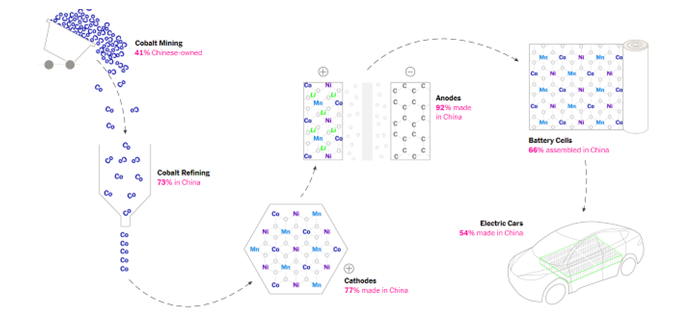

Enabling access to banking is an early example of how digital technology is being utilised – banking penetration went from 20% of the population in 2008 to 100% by 2017/18. During the pandemic, banking access – linked up to the Aadhaar digital identification program and the United Payments Interface (UPI) – was pivotal in enabling the swift and targeted transfer of around $4.5 billion worth of benefits to 160 million beneficiaries.

India has emerged as a leader in the development of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), which is pervasive and inclusive with 1.36 billion unique digital IDs, facilitating tens of billions of payments each year, and covering 10 million GST-registered companies.

At the heart of this is UPI, a real-time payments system established in 2016 which has quickly become the world’s largest real-time digital payments market. In 2020, 25.5 billion transactions were registered on UPI. The technology allows users across India to use their smartphones to quickly set up and transact using cardless accounts accessed using personalised QR codes, and utilise services including overdrafts, autopayments and voice-based payments. The system is even being expanded internationally, enabling free and instant cross-border transactions (versus pricey transactions via SWIFT) in a number of different currencies to and from India, which is the world’s largest remittances market – worth over US$100 billion in 2022 (World Bank).

This has been a game-changer for India. Besides our oft-quoted reforms (bankruptcy law, demonetisation, clean water and electricity roll out, infrastructure spending, public toilets in rural areas, etc.), UPI has proven incredibly successful and has been crucial in ensuring welfare payments get to the right people, reducing waste and corruption, increasing tax revenues and giving more people bank accounts and phones.

What does this all mean for investors in emerging markets? While positive, initiatives like UPI, bankruptcy reform or sanitation may seem relatively trivial in isolation. However, it is the compounding effect of these incremental steps over a sustained period that can create a virtuous circle that unlocks the next upward shift on the development ladder. For a country the size of India, that progress will see several hundred million Indians join the formal economy and accumulate wealth, which can in turn present a host of opportunities for investors with the framework to harness these structural tailwinds.