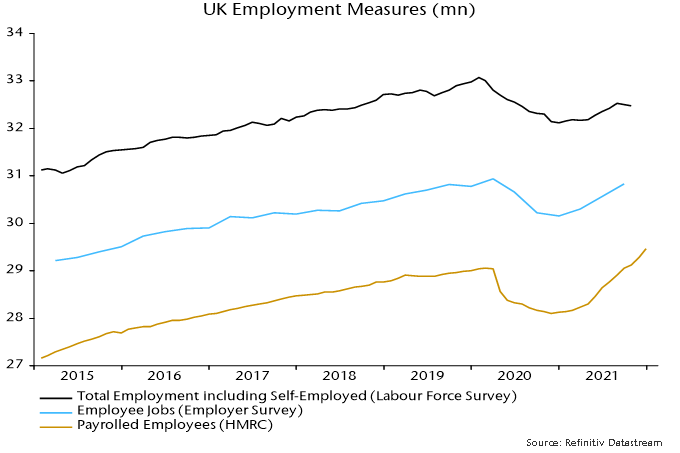

UK payrolled employment rose solidly again in November, while pay growth numbers for October surprised to the upside. It has been suggested that this news reinforces the case for a Bank rate hike of at least 50 bp this week.

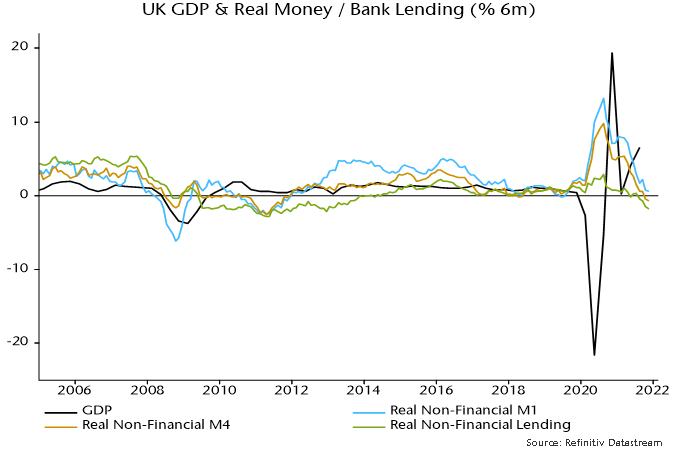

Employment is a lagging economic indicator. There is ample coincident evidence that a recession is under way. Annual broad money growth – as measured by non-financial M4 – is down to 3.4%, a level suggesting a medium-term inflation undershoot. The view here is that any rate rise this week will be a mistake.

The monthly payrolled employment measure has a short history but it correlates closely with the quarterly (and less timely) Workforce employee jobs series. In the 2008-09 recession, the latter measure peaked two quarters after GDP.

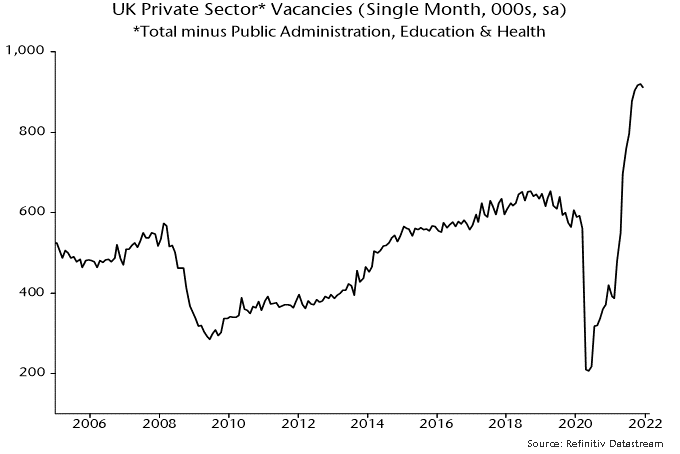

Labour market indicators that lead employment / unemployment include the stock of vacancies and average hours worked. These indicators are usually roughly coincident with GDP.

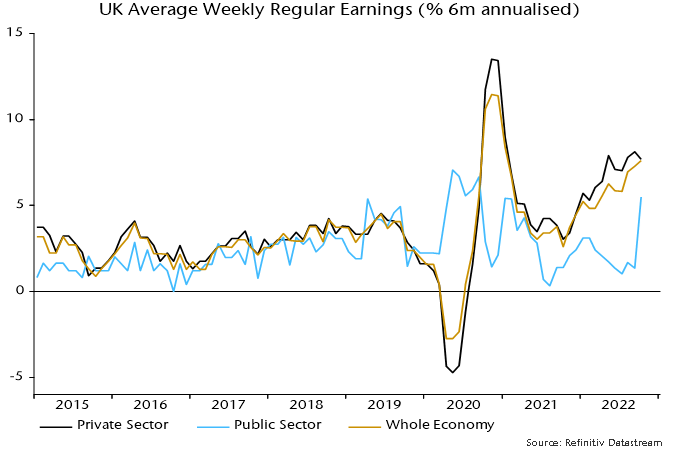

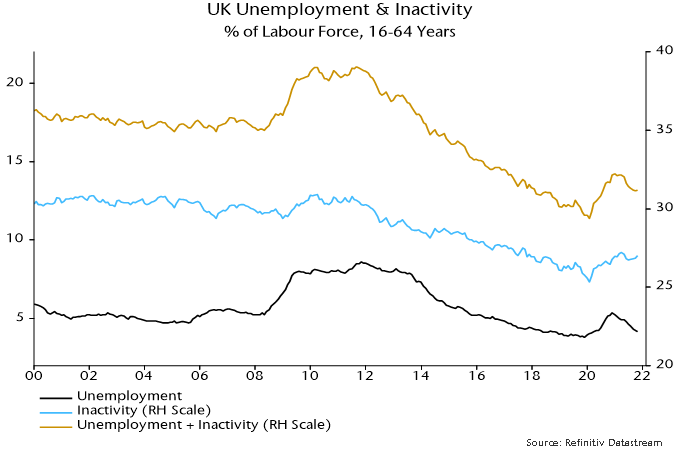

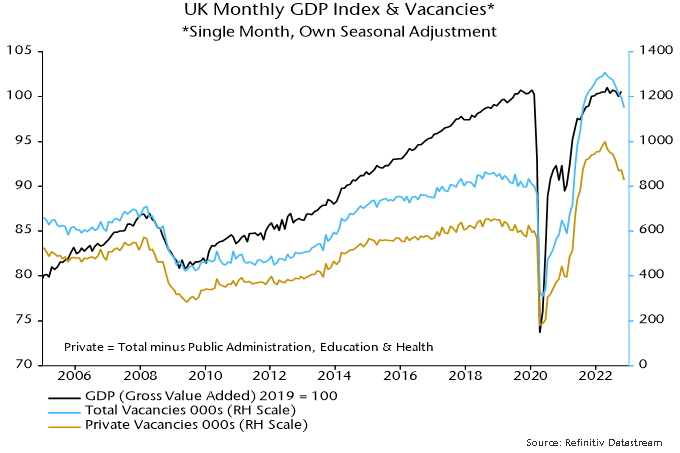

The headline vacancies series is a three-month moving average but non-seasonally-adjusted single-month numbers are available and can be adjusted using a standard procedure. The resulting series peaked in April, one month before GDP, and fell again in November – see chart 1. The recent pace of decline is comparable with the 2008-09 recession.

Chart 1

The weak November vacancies number suggests that GDP contracted significantly last month after October’s catch-up from reduced September activity due to the Queen’s funeral.

Average weekly hours tell a similar story. The series, which is available only as a three-month moving average, peaked in March and fell again in October, reaching its lowest level – excluding the pandemic recession – since 2012.

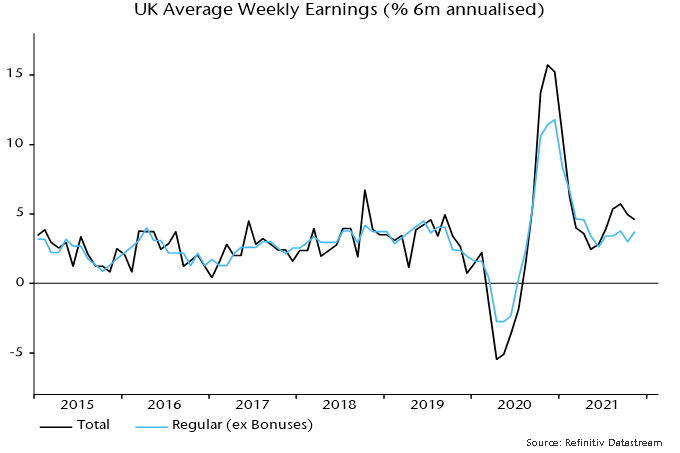

Should the MPC react to strong pay numbers? The monetarist view is that pay pressures are an effect rather than a cause of high inflation and will moderate as the dramatic slowdown in money growth since 2021 feeds through to slower price rises.

The latest upside surprise, in any case, reflects a belated catch-up in public sector pay; six-month growth of private sector regular pay is high but moving sideways – chart 2. A public sector pay pick-up may be bad news for real government spending and / or the public finances but will have little effect on the pricing behaviour of private sector suppliers of goods and services – especially against a backdrop of deepening recession and a loosening labour market.

Chart 2