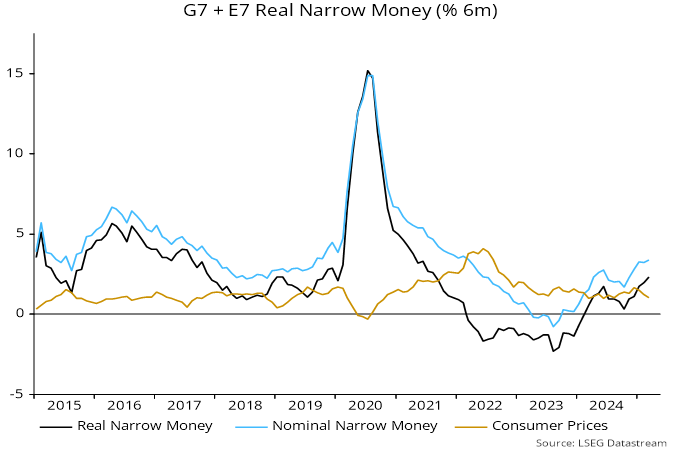

A cyclical forecasting framework implies that current economic events will contain echoes of developments at the same stage of previous cycles.

Similarities should be more pronounced at around 18- and particularly 54-year frequencies, corresponding to average lengths of the housing and Kondratyev inflation cycles respectively.

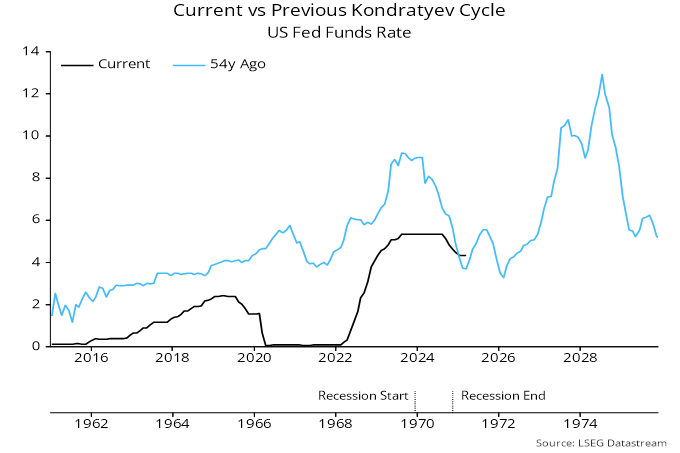

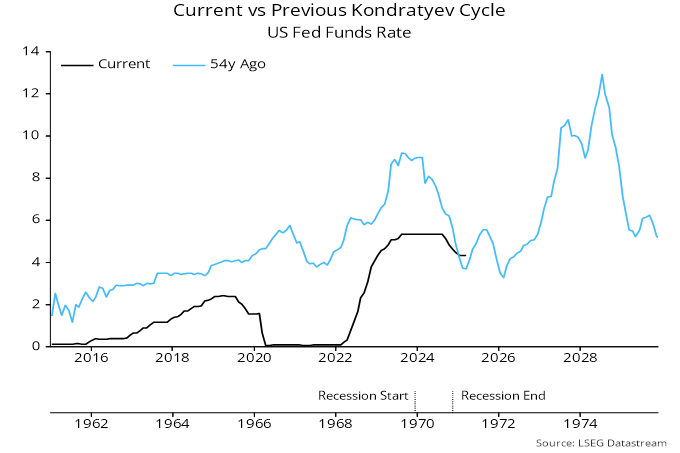

A previous post noted the similarity of Fed tightening episodes in 1967-69 and 2022-23. The Fed funds rate (month average) rose from peak to trough by 540 bp and 530 bp respectively, topping in August 1969 and August 2023, exactly 54 years later – see chart 1.

Chart 1

The US economy entered a recession at the end of 1969. GDP was recovering by Q2 1970 but suffered a second hit from a prolonged auto strike.

The Fed cut rates much more aggressively than recently but reversed course temporarily from early 1971 as the economy rebounded strongly and inflation remained high. The current Fed pause has occurred at the same cycle time.

Inflation fell sharply into 1972, mirroring a big slowdown in broad money growth two years earlier. The Fed resumed easing later in 1971, with the funds rate reaching an ultimate low in February 1972.

A possible scenario is that President Trump’s tariff shock triggers the recession “missing” from the current cycle, causing the Fed to ease aggressively later in 2025, with rates and inflation falling to lows in 2026 corresponding to those reached in 1972.

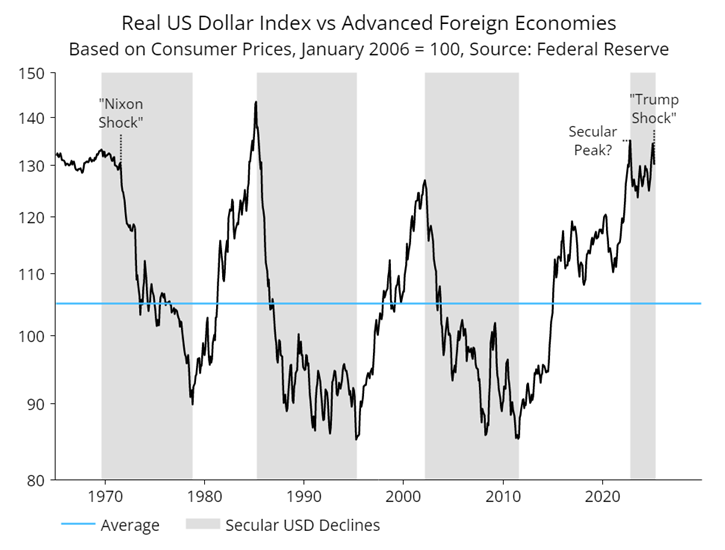

US disruption to global economic relations is itself is strongly reminiscent of policy developments 54 years ago. In August 1971, President Nixon shocked trading partners by suspending convertibility of the dollar into gold within the Bretton Woods system while imposing a 10% tariff on imports.

The backdrop was a US balance of payments deficit and an accelerating loss of gold from US reserves. According to a Federal Reserve history of the period, President Nixon blamed the deficit “on unfair trading practices and other countries’ unwillingness to share the military burden of the Cold War”. Sound familiar?

The “Nixon shock” triggered a crisis, with global policy-makers fearing that “international monetary relations would collapse amid the uncertainty about exchange rates, the imminent spread of protectionism, and the looming prospects of a serious recession”.

The crisis was resolved, at least temporarily, by the December 1971 Smithsonian Agreement, involving trading partners agreeing to revalue their currencies against the dollar in return for the removal of tariffs. “The net effect was roughly a 10.7 percent average devaluation of the dollar against the other key currencies … Foreign nations also agreed to comply with Nixon’s request to lessen existing trade restrictions and to assume a greater share of the military burden.”

Could a revaluation of currencies against the dollar be part of a “deal” to end the current crisis, once President Trump comes to recognise that the economic costs of his high tariff policy greatly exceed any benefits?

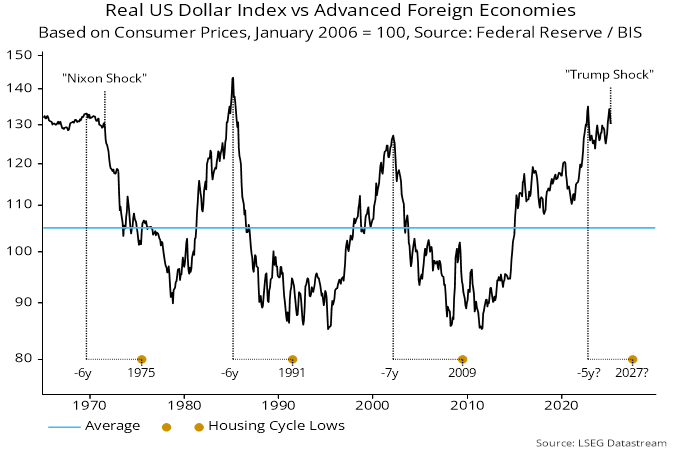

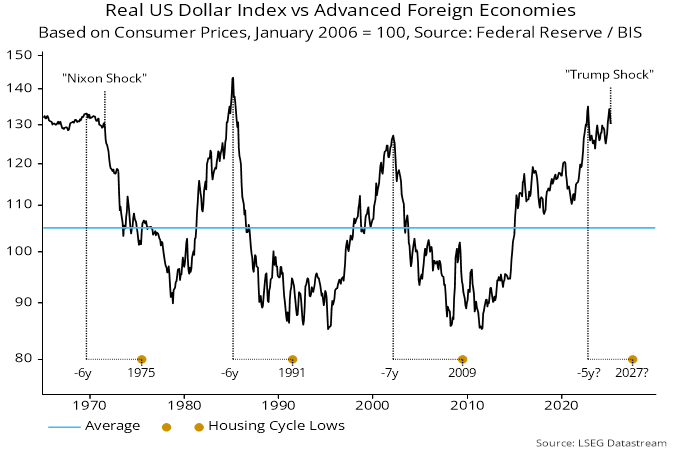

The Nixon shock occurred with the real trade-weighted value of the dollar at a similar premium to its long-run average to today. The shock accelerated a secular decline into and beyond the following housing cycle trough – chart 2.

Chart 2