I recently spent six weeks in Asia, including four weeks travelling to Sapporo and Tokyo in Japan to attend two major investor conferences hosted by SMBC Nikko and Daiwa and meet with over 50 Japanese-listed companies.

My trip also included two weeks in China to celebrate the start of the Year of the Dragon, plus a week in Shanghai and nearby Jiangsu province visiting various companies and doing due diligence on existing and prospective holdings.

Japan’s investment appeal

Many may be surprised to learn that our highest country allocation is to Japan at over C$2.3 billion of our approximately C$9 billion total AUM. Across our Global, International and sustainable strategies, we own around 25 Japan-based companies in 10 different sectors, from Asics and Sega Sammy (Sonic) to Hoshino Resorts and Sakata Seed.

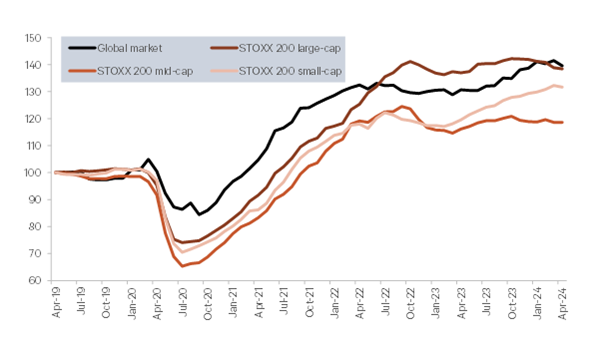

Year-to-date, the Nikkei Index is one of the top-performing developed market, up 13% in JPY or 3% in US$. The Nikkei recently broke its previous record set in December 1989. Yes, over 34 years ago. Was Warren Buffett onto something when he invested in Japan’s five largest trading companies back in August 2020?

Skepticism about the country due to its apparent structural weaknesses suggests that this rally is unsustainable. However, as anyone who reads our weeklies knows, we are optimistic on Japan and have made a point of visiting many times over the years. In the past year alone, five of us have travelled there for onsite company visits and conferences.

A resurgence in corporate Japan

Our January 25th weekly explored Japan’s improved corporate governance. Corporate reforms are gaining significant momentum. Since mid-January, 54% of listed companies have disclosed initiatives to reduce capital costs and enhance valuation. This topic was often on the first page of investor presentations at the two conferences I was at.

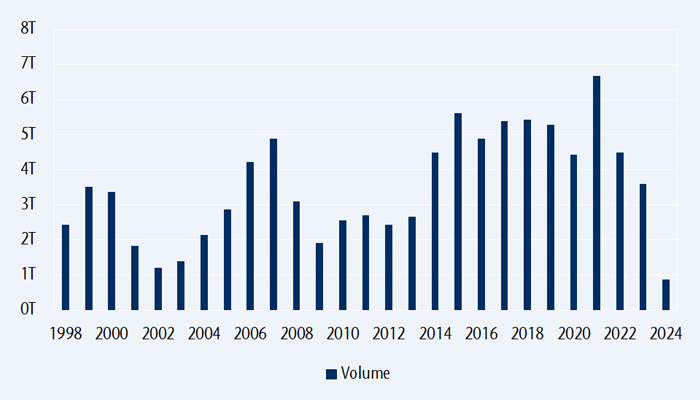

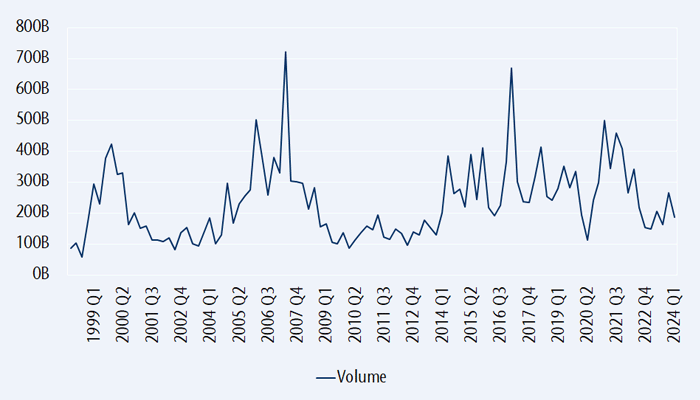

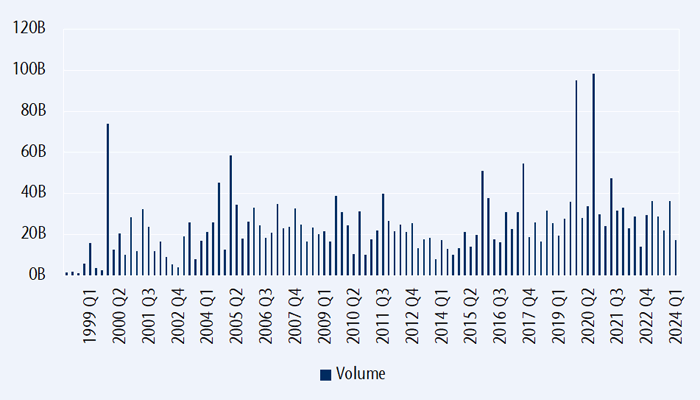

Companies announcing buybacks exceeded 1,000 in 2023 and amounted to over ¥9.6 trillion, with dividend payments also seeing notable increases to more than ¥15 trillion last fiscal year and growing. Stock splits are becoming common, cross-shareholdings are being sold and M&A is on the rise, albeit with private equity players still having a small role (less than a quarter of all transactions).

The Nippon Individual Savings Account (NISA) boost

The revamped NISA now allows for an annual contribution limit of ¥3.6 million (US$24,300) per person, up from ¥1.0 million, and a total balance of ¥18 million to be permanently tax exempt. As of June 2023, there were 19.4 million NISA accounts, a modest number given Japan’s population and that households were holding a record ¥2,115 trillion in financial assets, more than half of it in cash. Approximately 1 million NISA accounts are opened each month.

Foreign investment and demographic shifts

Japan is experiencing a considerable wealth transfer set to continue over the next decade due to its aging population, especially notable among Gen-Z (1997-2012) who are more open to equity investments compared to older generations. Foreign investors are still underweight.

Deflation forever?

Japan seems to have finally escaped deflation. Core inflation rose to 2.8% year-on-year in February and should continue to stay above 2% if the latest wage increase is an indication. In March, Japan’s union group announced its biggest wage hike in 33 years at 5.85%. We believe that higher wages will ultimately encourage consumption. Most companies we met told us that their reluctance to raise prices to their customers is no more, with many now doing just that or walking away from low-margin businesses. As an example, the country’s largest beer and beverage company, Asahi, raised its prices for the first time in 14 years in October 2022 and three times since for a total increase of around 20%.

I encourage you to re-read some our previous comments on Japan as far back as 2009:

- December 9, 2009: Global Alpha manager commentary

- September 13, 2019: Japan’s standards of corporate governance

- November 22, 2019: Japan’s work style reform

- July 22, 2021: Japan: Land of the rising ESG

- December 1, 2022: Time to visit Japan

- May 5, 2022: The myth of inflation in Japan

- October 13, 2023: Japan’s long-awaited recovery

Japan’s visa policy changes and their impact on immigration

Another was about Japan’s updated visa policy, from August 3, 2018: Japan’s new visa policy. We touched on the view that Japan was closed to immigration and that its low birth rate would lead to a significant population decrease and inexorable decline.

What struck us visiting Japan this time was how many non-Japanese people work in the hospitality industry. They hail from many countries, including China, India, Sri Lanka and Vietnam and all speak Japanese and English. Back when we wrote the comment in 2018, there were 1.3 million foreign workers in Japan, compared to 486,000 a decade earlier and the goal was to increase by 500,000 by 2025. Japan achieved this goal much sooner, with 2.1 million foreign workers there in 2023. The country is entering an era of mass immigration and half of Japan’s prefectures saw net population increases last year. According to the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Japan needs 6.8 million foreign workers by 2040 to meet its growth targets. New immigration and visa policies being introduced this year will make it much easier for foreign workers to permanently settle in Japan and eventually obtain citizenship.

Observations from China

Turning to China, we believe the negative sentiment towards the country is at an extreme. India’s market capitalization recently surpassed China’s despite having an economy a sixth of the size.

We see emerging market funds exclude China and the geopolitics are at their worst in my career as an investor.

Yet, the sentiment in China is slowly improving. I spent a month there last May when the shock of the COVID-19 lockdown was fresh in people’s memory. This February, although still subdued, sentiment seemed slightly better.

Economic indicators like the PMI Composite Index – now above 50 – are improving. CPI is still negative, but with rising commodity prices, China will likely avoid a deflationary spiral. Industrial production and exports are also on the rise and retail sales are growing faster than GDP.

The property market will probably never be an engine of growth again, but the service sector, led by healthcare and hospitality, may very well take the baton.

The negative news cycle about China that we see in North America is much different than in Asia. Japan’s relations with China are improving and China’s trade with its neighbours is increasing rapidly. Indonesia’s president-elect, Prabowo, visited China in early April, mentioning the importance of maintaining good ties with China and the US and condemning the China bashing. China is now the largest trading partner to over 120 countries, including Indonesia and also Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam.

Despite the Western media’s negative rhetoric, China is a very important market for many large US and foreign multinational brands, including Apple, BMW, Uniqlo and Zeiss. In the past few weeks, many American CEOs have visited China and met with President Xi. Janet Yellen was also there recently and President Biden is scheduled to talk to China in the coming days. Let’s hope that they can restore the productive dialogue.

China’s green revolution

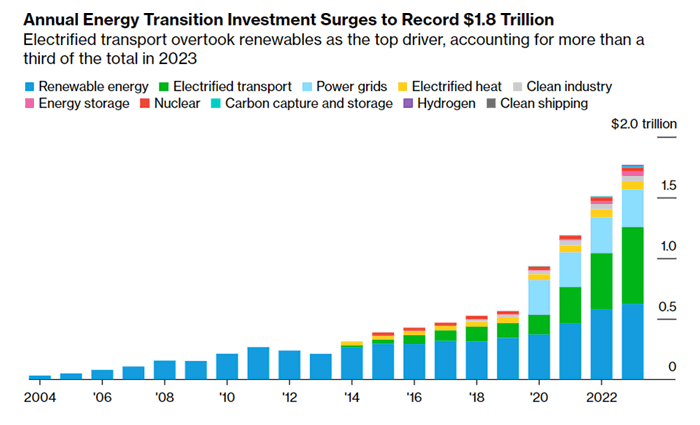

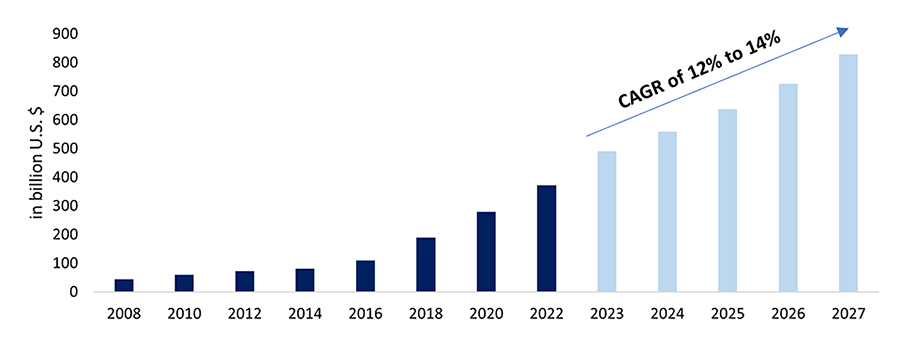

China’s spent 40% more on clean energy in 2023 compared to 2022, or $890 billion – equivalent to the GDP of Switzerland or Turkey.

Also last year, China installed 217 GW of solar power, up 55% over 2022 and more than the US has in its entire history. Total solar power capacity in China is now over 609 GW. Canada has 4.4 GW; the US, 179 GW. Wind power installation increased 21% to more than 441 GW. Canada has 19 GW and the US has 141 GW.

BYD overtook Tesla as the largest NEV car company in 2023 and Xiaomi has now reclaimed a #2 position in the Chinese smartphone market.

So, regardless of the negative news, we are generally constructive on China, have made a number of investments in the country and continue to find attractive investment ideas there.

Reflecting on a phase of resilience and renewal

Our travels through Asia reinforce an evolving narrative not just of growth but of transformation. The confluence of Japan’s market performance and its emerging immigration landscape paints a picture of a nation redefining itself. Meanwhile, China’s quiet resurgence, often obscured by geopolitical noise and prevailing sentiments, is creating an environment of untapped opportunities that invites a deeper understanding beyond surface-level perceptions. We are ready to embrace the potential of these markets to generate alpha for our clients.