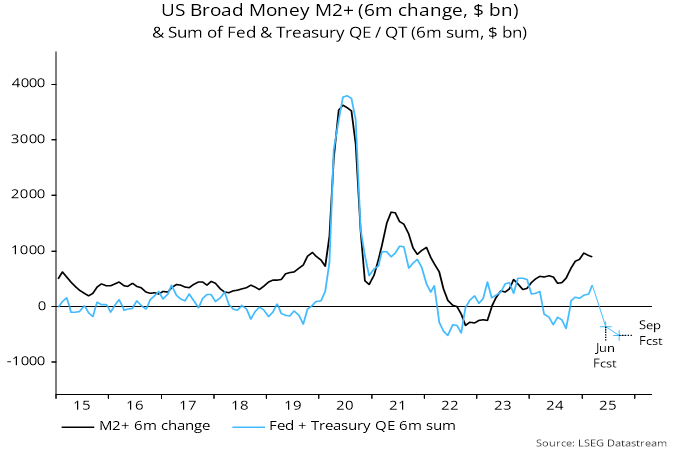

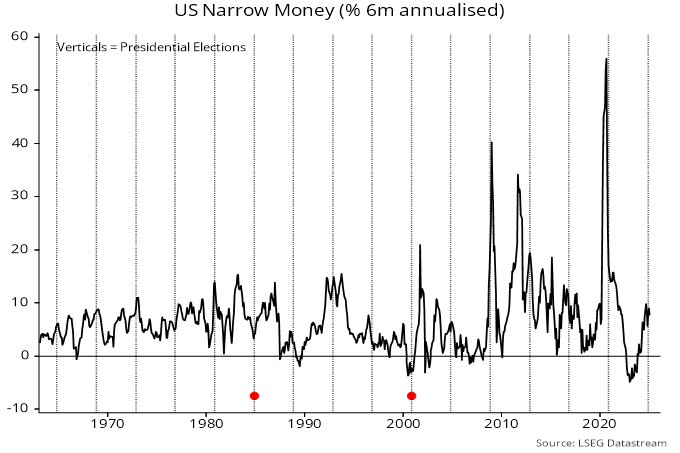

Credit tightening in private markets may mark the end of a boom in US bank lending to shadow banks, with negative monetary implications.

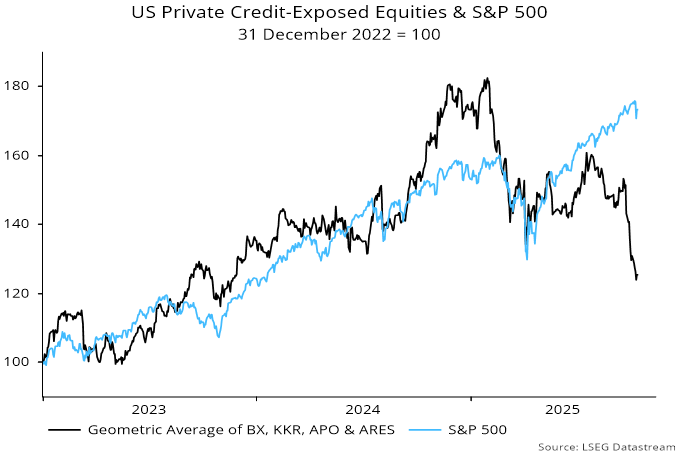

Equity prices of major players in private credit have fallen sharply in the wake of the Tricolor / First Brands bankruptcies, with an average down by 31% from a January peak – see chart 1.

Chart 1

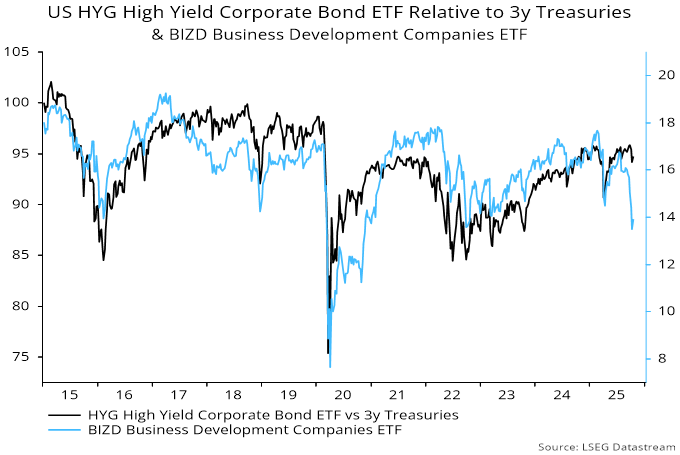

Increased risk aversion is also evident in lower prices / higher yields of traded private credit instruments, such as the VanEck Business Development Companies ETF (BIZD), which usually mirrors moves in high yield spreads but has opened up a wide gap – chart 2.

Chart 2

Commercial bank lending to shadow banks / private credit has been booming, with the “all other” category containing loans to non-bank financial institutions up by 14.5% in the year to September, accounting for 2.9 pp of overall bank loan growth of 4.9% – chart 3*.

Chart 3

Traditional loan categories – C&I, real estate and consumer – grew by only 2.5% over the same period.

Lending to shadow banks is likely to slow as private credit players rein in activity and loan officers tighten standards. A normalisation could cut 2 pp or more from annual loan growth, implying weaker broad money expansion unless offset by other “credit counterparts”**.

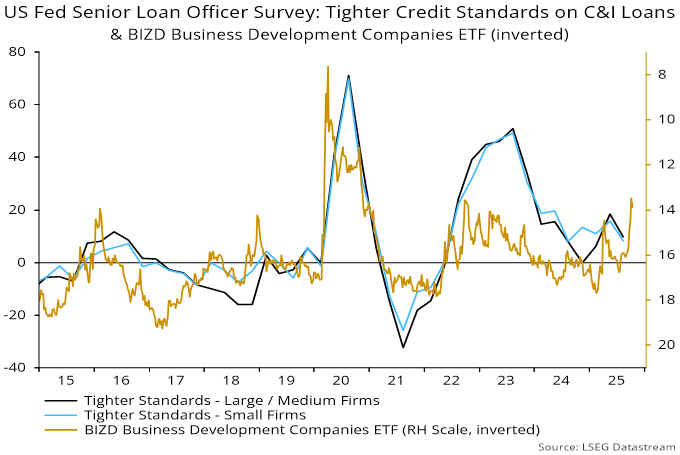

Credit tightening could extend to other loan categories unless private markets recover – chart 4. (Note that the reporting window for the October Fed senior loan officer survey, to be released in early November, may already have closed, so the results may not fully reflect recent developments.)

Chart 4

*Growth numbers are break-adjusted – levels series have been distorted by recent reporting changes.

**Some combination of increased monetary deficit financing, a stronger basic balance of payments or reduced non-deposit funding.